تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 12-7-2016

Date: 18-7-2016

Date: 18-7-2016

|

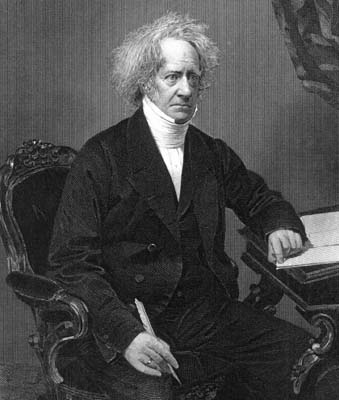

Born: 7 March 1792 in Slough, Buckinghamshire, England

Died: 11 May 1871 in Hawkhurst, Kent, England

John Herschel was the son of William Herschel, the astronomer who discovered Uranus. His mother Mary Pitt was the daughter of a wealthy merchant. She was 38 years old when she married William Herschel, her first husband and her only child having both died. When John Herschel was born in 1792 William was 55 years old and Mary was 42. In addition to his parents, his aunt Caroline Herschel was another important figure in John Herschel's upbringing.

William Herschel was not only a leading astronomer but he also had a great talent for music. Both he and his sister Caroline Herschel were extremely musical, and they had both used their musical talents to help augment their income after first arriving in England. John was brought up in Observatory House, with its 40 foot telescope, where music, science and religion were dominant. Caroline Herschel had left her brother's home when he married, but she continued to come to Observatory House every day to help William reduce his data and she proved an outstanding teacher to John, carrying out experiments in physics and chemistry with the young boy.

Schooling did present some problems for John. After studying at Dr Gretton's School in Hitcham, he was sent to Eton College when he was eight years old but he was bullied by the other boys. He was removed from the school by his mother after a few months. In addition to schooling at Clewer and Hitcham, John was tutored at home by Mr Rogers, a private mathematics tutor, to prepare him for university. He entered St John's College Cambridge in 1809.

As an undergraduate Herschel made friends with Peacock and Babbage. In 1812 the three undergraduates founded the Analytical Society which had as its aim the introduction of Continental methods of mathematical analysis into English universities. It is fair here to say that the aim was to bring Continental mathematical theory into English universities since the Scottish universities were at this time more progressive. We should also say that the Analytical Society was not the first move towards Continental mathematics in England, for Woodhouse who was one of Herschel's lecturers at Cambridge, had written a fine book which took the Leibniz approach to the calculus rather than Newton's approach. Yet the mathematical syllabus at Cambridge reflected none of the theories of d'Alembert, Leibniz (in particular Euler's development of this approach), or of the more algebraic approach of Lagrange.

Herschel, together with Peacock, translated Lacroix's Traité du calcul différentiel et du calcul intégral which examined these different approaches to the calculus. Herschel did not offer these three approaches with equal recommendation for he believed that the algebraic approach of Lagrange was the right one. However the Analytical Society did not survive for very long. Herschel graduated in 1813 taking first place in the final examination. Peacock came second to Herschel while Babbage had withdrawn mainly because he could not compete with Herschel and he was not prepared to enter a competition which he knew that he could not win.

Following his graduation Herschel became first Smith's prizeman and was elected a fellow of St John's College. Also in 1813 he was elected as a fellow of the Royal Society of London, having published a mathematics paper On a remarkable application of Cotes's theorem in the Transactions of the Royal Society.Despite the demise of the Analytical Society Herschel continued to work on mathematics. He studied algebras and published papers on trigonometrical series. Among many mathematical works he published a two volume book in 1820 on examples of applications of finite differences. His mathematical work continued up to 1820 (and his interest in mathematics was evident in many later works on other topics) but even before 1820 his interest in other subjects had begun to take him away from research in mathematics.

It is interesting to think that it was in some ways due to Herschel's remarkable all round abilities that he failed to make an advance of the depth that he was clearly capable of in any of the subjects that he studied. In all of them he could have been the person that we remember today as the world leader of his time. Yet the fact that he contributed to so many areas meant that he had usually moved on to something else when he might have been consolidating his work in a single area. Certainly his mathematical work, important as it was, never had the influence which he might have been able to have achieved had he continued to work in the area.

Perhaps most surprising of all was the decision that Herschel made after graduating. He decided to enter the legal profession, much against the advice of his father who wanted him to join the Church, and he went to London in February 1814 to begin training. It was not long before he found that it was not right for him and he wrote to Babbage in September 1814 saying that he would stick it out since it was his chosen career. However, after 18 months, he gave up his legal training and returned to Cambridge as a tutor and examiner in mathematics.

Herschel spent a holiday with his father during the summer of 1816. He seems to have decided during this holiday to turn to astronomy, almost certainly influenced by the fact that at 78 years of age his father's health was failing and there was nobody else to continue his father's work. He wrote on 10 October 1816 to Babbage (see C A Ronan's article in [6]):-

I shall go to Cambridge on Monday where I mean to stay just enough time to pay my bills, pack up my books and bid a long - perhaps a last farewell to the University. ... I am going under my father's directions, to take up the series of his observations where he has left them (for he has now pretty well given over regular observing) and continuing his scrutiny of the heavens with powerful telescopes ...

Indeed John Herschel began to undertake work in astronomy from this time although he also studied other topics. Even before his first astronomy paper was published, Herschel published details of his chemical and photography experiments in 1819 which, 20 years later, would prove of fundamental importance in the development of photography. He was very much involved with the founding of the Astronomical Society in 1820 and he was elected vice-president at the second meeting of the Society when the officers of the Society were elected. Herschel's great versatility is shown by the fact that in 1821, having recently become involved in astronomy and chemistry, he was awarded the Copley Medal of the Royal Society of London for his work on mathematical analysis.

Babbage and Herschel remained close friends and the two travelled together to Italy and Switzerland in 1821. They shared a love of climbing mountains but their exploits here were not simply for pleasure as Herschel continually learnt about science from his environment. Other trips abroad by Herschel included one in 1822 and another with Babbage in 1824. These trips included visits to other scientist, for example while in Paris Herschel and Babbage had discussed topics of common interest with Arago, Laplace and Biot. On the 1824 trip Herschel had visited Fraunhofer and had met with Fox Talbot who was visiting Fraunhofer at the time. He also visited Pfaff, who was working on a German translation of his father's work, and his aunt Caroline Herschel who had returned to Hanover after the death of her brother (John Herschel's father) in 1822.

In fact 1822 was the year in which John Herschel published his first paper on astronomy, a relatively minor work on a new method to calculate eclipses of the moon. His first major publication in astronomy was a catalogue of double stars which he published in the Transactions of the Royal Society in 1824 and for which he received honours. The Paris Academy awarded him its Lalande Prize in 1825 and the Astronomical Society awarded him its Gold Medal the following year.

The work on double stars had been undertaken as a continuation of his father's work which attempted to measure the parallax of a star. The parallax is the apparent change in position of a relatively nearby star against the background of very distant stars due to the change in position of the earth in its orbit around the sun. John Herschel published an important paper on this topic in 1826 but did not succeed in determining the parallax of any star. He continued to work on double stars until 1833, in particular he developed methods to determine the orbits of those double stars which orbited a common centre of gravity and for this work he received the Royal Medal of the Royal Society in 1833. Bessel was the first to demonstrate the parallax of a star, publishing his results in 1840.

In 1830 Herschel published his famous treatise Discourse on Natural Philosophy the importance of which is beautifully described by Faraday in writing to Herschel:-

... when your work on the study of Natural Philosophy came out, I read it, as others did with delight. I took it as a school book for philosophers, and feel that it has made me a better reasoner and even experimenter, and has altogether heightened my character, and made me, if I may be permitted to say so, a better philosopher.

Herschel's involvement with the Royal Society had important influences on his career. He had been elected Secretary of the Society in 1824 (although he resigned in 1827) and, in 1831, he was proposed by Babbage for President of the Royal Society. This was part of a battle that was going on in the Society between reformers and traditionalists, Herschel being the champion of the reformers. In a slightly embarrassing episode for Herschel, he failed narrowly to be elected, the traditionalists winning the day. He had been elected as President of the Astronomical Society in 1827 and he was knighted in 1831 so he received great recognition despite his disappointment with the Royal Society.

The Royal Society episode may have been the main reasons why Herschel decided to make a long visit to the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. Also it became possible at this time because of the death of his mother Mary Herschel in 1832. The Royal Observatory had been completed at the Cape of Good Hope in 1828 with the scientific aim to catalogue interesting astronomical objects which could not be observed from the northern hemisphere. Herschel sailed for South Africa in 1833, taking with him his own 20 foot refractor telescope. He travelled with his family, having married Margaret Brodie Stewart four years earlier, and their ship reached South Africa in January 1834.

Among the many important scientific advances made by Herschel in South Africa was his observations of Halley's comet on its 1835 return. He recognised that the comet was being subjected to major forces other than gravitation and he was able to calculate that the force was one repelling it from the sun. This could in some sense be said to constitute the discovery of the solar wind which is indeed the reason for the repulsive force discovered by Herschel. He also made the important discovery that gas was evaporating from the comet.

The geologist Lyell saw the irony in the fact that Herschel had done this work in South Africa because he failed to be elected President of the Royal Society. He wrote (see for example [6]):-

Fancy exchanging Herschel at the Cape for Herschel as President of the Royal Society, which he so narrowly missed being, and I voted for him too! I hope to be forgiven for that.

In 1838 Herschel returned to England not having had much time to reduce the many observations that he had made while there. His intention was to work on these as soon as he returned but he was kept so busy with other events that this task was not completed until 1847. Despite the delay, the publication was an event of great importance and Herschel received his second Copley Medal from the Royal Society for this work. The events which prevented him from working on his observations after his return were partly non-scientific such as his investment to a baronetcy in June 1838 which he accepted with considerable reluctance. The main distractions were, however, scientific ones.

On 22 January 1839 Herschel heard of Daguerre's work on photography from a casual remark in a letter written by Beaufort to Margaret his wife. Without knowing any details, Herschel was able to take photographs himself within a few days. Fox Talbot visited him on the 1 February to discuss their separate experiments in photography. In his article in [6] Roberts quotes from a letter by Herschel's wife:-

I happen to remember well the visit to Slough of Mr Fox Talbot, who came to show Herschel his beautiful little pictures of Ferns and Laces taken by his new process. - when something was said about the difficulty of fixing the pictures, Herschel said "Let me have this one for a few minutes" and after a short time he returned and gave the picture to Mr Fox Talbot saying "I think you'll find that fixed" - this was the beginning of the hyposulphite plan of fixing.

Indeed Herschel was able to achieve this remarkably rapid breakthrough due to the work that he had conducted and published in 1819 on chemical processes related to photography. Herschel went on to publish a number of further papers on photography, in 1839, 1840 and 1842. In fact many people have wondered why Herschel himself never made the steps which would have led to his being recognised as the inventor of photography. There was a period of around 20 years from the time of his 1819 work when he might have made the breakthrough but again it was probably due to his wide ranging talents that he failed to do so. Not only did his talents take him into a wide range of other activities but his great skill as an artist meant that he had less need to invent photography than most others!

In 1850 Herschel made a rather strange decision as to the future direction of his career. He had turned down entering parliament as a Cambridge University member and he had also turned down a proposal that he become president of the Royal Society. He did become rector of Marischal College in Aberdeen in 1842 and served as president of the British Association at Cambridge in 1845. In 1850, however, he accepted the post of Master of the Mint. He thus became head of the Mint at a very difficult time, with a major reform already agreed but its implementation not begun. It was not a job which Herschel found to his liking. There were difficulties in dealing with staff, difficulties in dealing with the Treasury, but perhaps most significantly of all to Herschel, he no longer could pursue his scientific interests.

Herschel was a scientist by nature, not a business man. After difficult years, frequently separated from his family by the demands of the job which he tried his best to do well, he resigned. His health had suffered through the stresses of the post and it must have come as a great relief to him to be free of the problems. He essentially retired to Collingwood at this stage in his career being 63 years of age. To say he retired needs of course to be qualified with the remark that throughout his life he never held any paid scientific post. He certainly did not retire from scientific work but, free of the huge demands of the job at the Mint for which he had received a fair salary, he was able to complete many tasks which he and his father had started but had never reached completion. As Tait wrote (see for example [10]):-

Every day of Herschel's long and happy life added its share to his scientific services.

Although he made no major breakthroughs for which he is remembered today he was considered by many of his contemporaries as the leading scientist of his day. Biot considered him the natural successor to Laplace when he died in 1827. In the obituary [13] it is remarked:-

In John Frederick William Herschel British science has sustained a loss greater than any which it has suffered since the death of Newton, and one not likely to be replaced...

The article [13] then goes on to say that of even higher value than his research:-

... was the influence of his teaching and example in wakening the public to the power and beauty of science, and stimulating and guiding its pursuit.

1. D S Evans, Biography in Dictionary of Scientific Biography (New York 1970-1990).

http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-2830901974.html

2. Biography in Encyclopaedia Britannica.

http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9040234/Sir-John-Herschel-1st-Baronet

Books:

3. G Buttmann, The Shadow of the Telescope : a biography of John Herschel (New York, 1970).

4. A M Clerke, The Herschels and Modern Astronomy (1895).

5. D G King-Hele (ed.), John Herschel 1792-1871 : A bicentennial commemoration (London, 1992).

6. H Macpherson, Herschel (1919).

Articles:

7. W J Ashworth, Memory, efficiency, and symbolic analysis : Charles Babbage, John Herschel, and the industrial mind, Isis 87 (4) (1996), 629-653.

8. W J Ashworth, The calculating eye : Baily, Herschel, Babbage and the business of astronomy, British J. Hist. Sci. 27 (95) (4) (1994), 409-441.

9. A M Clerke, Sir John Frederick William Herschel, Dictionary of National Biography XXVI (London, 1891), 263-268.

10. A Chapman, An occupation for an independent gentleman : astronomy in the life of John Herschel, Vistas Astronom. 36 (1) (1993), 71-116.

11. S Moore, A newly-discovered letter of J F W Herschel concerning the Plumian Professorship, J. Hist. Astronom. 25 (2) (1994), 142-143.

12. Obituary of Sir John Frederick William Herschel, Proceedings of the Royal Society 20 (1872), xvii-xxiii.

13. C A Ronan, John Herschel (1792-1871), Endeavour 16 (1992), 178-181.

14. P J Turvey, Sir John Herschel and the abandonment of Charles Babbage's Difference Engine No. 1, Notes and Records Roy. Soc. London 45 (2) (1991), 165-176.

15. M V Wilkes, Herschel, Peacock, Babbage and the development of the Cambridge curriculum, Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 44 (1990), 205-219.

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مدرسة دار العلم.. صرح علميّ متميز في كربلاء لنشر علوم أهل البيت (عليهم السلام)

|

|

|