Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension| Systematic and accidental lexical gaps explained by lexical hierarchies |

|

|

|

Read More

Date: 2023-03-16

Date: 2024-08-29

Date: 2024-07-23

|

The evidence above attests to the general need for lexical hierarchies as one of the structures of grammar. The hierarchies provide mechanisms for the blocking of certain obvious anomalies (e.g. (4aii)) and for the simplification of general selectional processes. The hierarchies also make predictions about the kinds of lexical items which can and cannot occur. That is, they provide a further basis for distinguishing lexical gaps which are systematically explained by the lexical structure of the language from those gaps which have no such explanation and are therefore ‘accidental’.

For example, the combination of the hierarchies as in (5) makes several claims about English lexical structure. The placement of finger, thumb and knuckle in the lower right of (5) strongly implies that the single lexical item indicating a ‘thumb- knuckle’ would be a regular extension of the present lexical system, since it would fit in the regular slot defined by the intersection of the existing Have and Be hierarchies (labeled ‘thuckle’). An instance of an irregular extension would be the word which is a unique part of both the wrist and the palm (labeled ‘wralm’ in figure 5). The irregularity of ‘wralm’ is explained by the fact that it would require a convergence of the hierarchy, which is not allowed in our formulation, for independent reasons. Thus ‘wralm’ would require two separate hierarchies and involve added complexity.

Surely this result is an intuitive one - the concept ‘thumb-knuckle ’ seems quite natural, but the concept of wrist-palm does not. It should be re-emphasized here that it is irrelevant to us whether or not these linguistic properties are reflections of something in the so-called ‘real world’. Our present quest does not include the source for linguistic structure but seeks to define the nature of the structure itself.

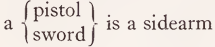

The hierarchy may also predict instances in which certain uses of words are dropped from a language. Consider the treatment of the word ‘sidearm’ in the Be hierarchy introduced above:

a sidearm is a weapon

These sentences indicate that it would have to be represented with a convergence on ‘ pistol ’ as in (19), or with two lexical instances of pistol as in (20):

If it were not for the fact that swords (and knives, technically) are sidearms it would be possible to formulate the hierarchy without any double dominance relations:

(21) weapon— gun — firearm — sidearm — pistol

In fact although we must allow for the possibility of the facts represented in (19) we have set up the formalism such that that type of structure involves a relatively large amount of complexity (as in (20)). (19) is represented as two separate hierarchies to avoid the double dominance of ‘ pistol ’. This offers an explanation of the tendency for the term sidearm (meaning both ‘ sword ’ and ‘ knife ’) to drop out of modern English, since its disappearance would reduce the complexity of (20) to (21).

As above we cannot rule out any particular aggregate of features (or possible constructions) on the basis of lexical structure rules since anything can occur as a lexical item. But the theory which we set up to represent lexical structure provides some formal basis for distinctions between lexical items which do occur. For instance, ‘shotgun’ is in an anomalous position in the hierarchy because of these sentences:

(22) (a) a shotgun is a firearm

(b) a firearm shoots bullets

(c) *a shotgun shoots bullets1

This requires us to mark ‘ shotgun ’ as an exception to the hierarchy (or to the rule which predicts features on the basis of the hierarchy.) That is, sentence (22 c) is marked as anomalous only itself as a process of an exceptional relation.

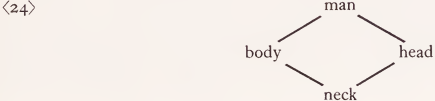

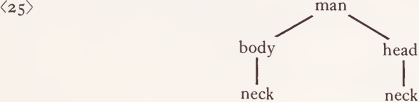

In certain cases the restriction on convergence in the hierarchy is supported directly by intuitions. For example, consider the word ‘neck’:

(23) (a) John’s head has a thick neck

John’s head was frozen, including his neck

(b) John’s torso (body) has a thick neck

John’s torso (body) was frozen, including his neck

For some, sentences (23 a) are correct and (23 b) are incorrect, for others the reverse is true. For many, both (23 a) and (23 b) are acceptable at different times, but not simultaneously: that is, there is no single lexical hierarchy which includes a structure like (24)

but rather the hierarchy is like (25).

It is tempting to ‘ explain ’ these facts as an ‘ obvious reflection of the fact that the neck resides between the body and the head ’. But there is nothing incompatible with the physical facts in an analysis which would delegate the neck as part of the ‘ head ’ and simultaneously part of the ‘ body ’. Thus, it is not ‘ reality ’ which disallows convergences of lexical hierarchies, but the non-convergent property of the lexical system itself.

1 These sentences seem to suggest that sentences like ‘ a gun is a cannon ’ must be generated in the grammar in order to account for the relative clause formation. In other words, the original motivation for the lexical Be hierarchy would seem to disappear. This argument is untenable, however, since it is necessary to postulate that a relativized noun is definite, referring to a specific noun: e.g. ‘a gun fires cannonballs if it (that gun) is a cannon’.

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتبة أمّ البنين النسويّة تصدر العدد 212 من مجلّة رياض الزهراء (عليها السلام)

|

|

|