النبات

النبات

الحيوان

الحيوان

الأحياء المجهرية

الأحياء المجهرية

علم الأمراض

علم الأمراض

التقانة الإحيائية

التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

علم الأجنة

علم الأجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

الأحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

الغدد

المضادات الحيوية

المضادات الحيوية|

Read More

Date: 5-11-2015

Date: 30-10-2015

Date: 5-11-2015

|

Skeletons

Everyone is familiar with the human skeleton and its role in supporting the body. Less familiar is the variety of skeletons in other animals and the additional functions they provide. Zoologists generally recognize three types of skeletons: a hydroskeleton, an exoskeleton, and an en- doskeleton.

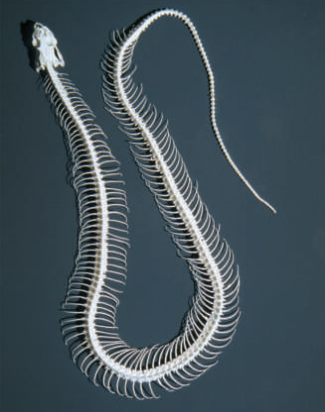

A snake skeleton

A hydroskeleton, also called hydrostatic skeleton, occurs in many soft- bodied animals, such as earthworms. A hydroskeleton is not bony, but rather is a cavity filled by pressurized fluid. Like air in a truck’s tires, the pressurized fluid keeps the body from collapsing from the forces of gravity or movement. By manipulating the pressure in different parts of the cavity, many soft-bodied animals can change shape and produce considerable force. Earthworms (annelids), for example, can burrow through soil using pressure in the hydroskeleton.

An exoskeleton is a hard, nonliving structure that encloses the rest of the body. The exoskeleton may consist of a single hard piece, like the shell of a snail, or it may have two or more hard pieces linked together by flexible tissue, as in a clam. In crustaceans, insects, spiders and other arthropods (Arthropoda), and also in some other groups of animals, the exoskeleton is called a cuticle. Animals with exoskeletons of two or more pieces can generally move the parts by means of muscles that attach to the inner surface. Exoskeletons have the advantage of providing protection from predators. (Consider the work it takes to eat a lobster.) One disadvantage, however, is that it restricts the growth of the animal inside it. Snails and many other mollusks solve that problem by continually enlarging their shells as they grow. An arthropod sheds (molts) the old cuticle as it grows, then it secretes a new and larger one.

Endoskeletons are enclosed in other tissues. The human endoskeleton does not offer much protection from predators, but it does a good job of keeping the body from collapsing into a helpless pile. It also provides sites for attachment of muscles. Most muscles connect two different bones, and almost all movements result when muscle contraction moves some bones relative to others.

The skeletons of humans and other vertebrates consist of differing proportions of cartilage and bone. Cartilage, being flexible yet resilient, is well suited to cushioning joints and changing size and shape easily. Cartilage serves as a temporary skeleton in the embryos of vertebrates. In sharks and a few other vertebrates, cartilage persists as the skeleton throughout life. In humans and most other vertebrates, most cartilage is gradually replaced by bone, but some remains as cushions for joints and flexible supports in the nose, ears, and trachea. Bone is, of course, harder and more rigid than cartilage, but it is still living tissue that can slowly adapt to strains imposed upon it.

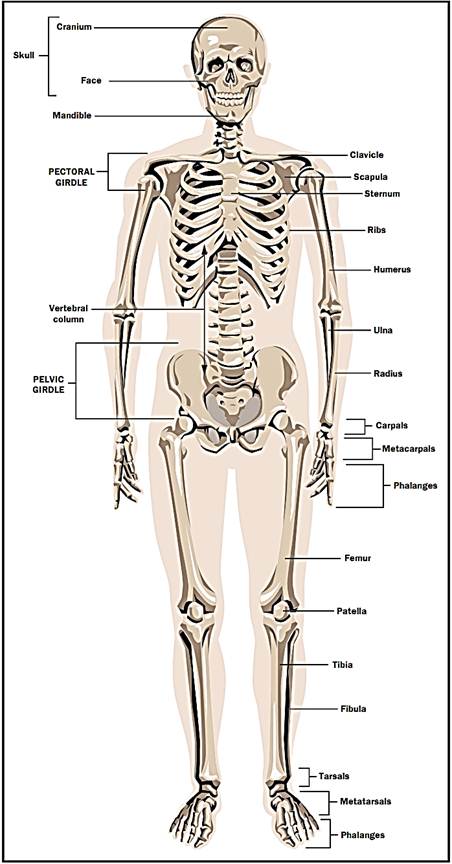

The 206 bones of the adult human skeleton occur in several distinctive parts of the skeleton. The skull, vertebrae, and ribs belong to the axial skeleton. The bones of the arms and legs and the pectoral and pelvic girdles are parts of the appendicular skeleton, which attaches to the axial skeleton.

Some of the major bones of the human skeleton.

References

Hickman, Cleveland P., Jr., Larry S. Roberts, and Allan Larson. Integrated Principles of Zoology, 11th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2001.

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اتحاد كليات الطب الملكية البريطانية يشيد بالمستوى العلمي لطلبة جامعة العميد وبيئتها التعليمية

|

|

|