Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-09-18

Date: 2023-11-28

Date: 3-6-2022

|

We start with a consideration of generic properties of fricatives, before looking at the specific details of individuals.

English has four pairs of fricatives which are traditionally said to be distinguished by voicing:  . Say the sounds continuously, alternating between the voiced and voiceless sound: e.g. [s::z::s::z::]. If you do this while covering your ears, you will hear the vocal fold vibration for the voiced sound conducted through your bones, but otherwise, the articulators remain in the same configuration.

. Say the sounds continuously, alternating between the voiced and voiceless sound: e.g. [s::z::s::z::]. If you do this while covering your ears, you will hear the vocal fold vibration for the voiced sound conducted through your bones, but otherwise, the articulators remain in the same configuration.

The phonetic detail of voicing is more complex for many speakers. We will see that the contrast actually involves a cluster of phonetic features, only one of which is vocal fold vibration.

If you compare a voiced and a voiceless pair of fricatives, such as [s z] or [f v], you will notice that there is less friction noise for a voiced fricative than for a voiceless one. The best way to hear this is to compare pairs, or near-pairs like ‘loser’, ‘looser’; ‘ever’, ‘heifer’. The reason for this difference is that when there is vocal fold vibration, the vocal folds are closed for about half of the time, and so there is less air flowing through the vocal tract. With voicing, the flow of air is reduced, and consequently the amount of friction noise is reduced.

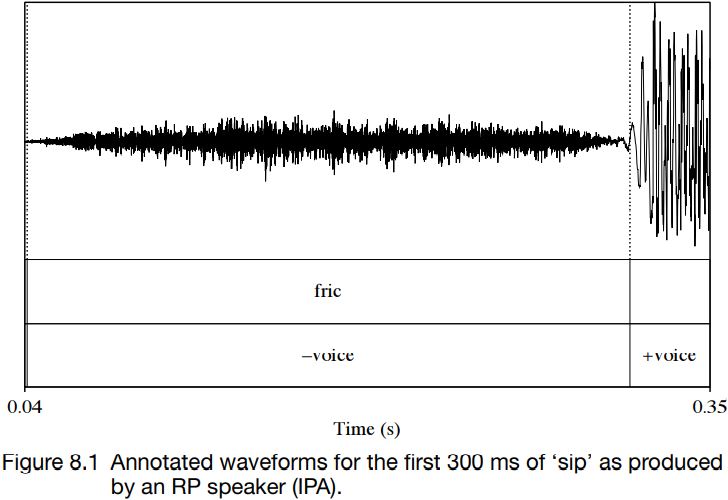

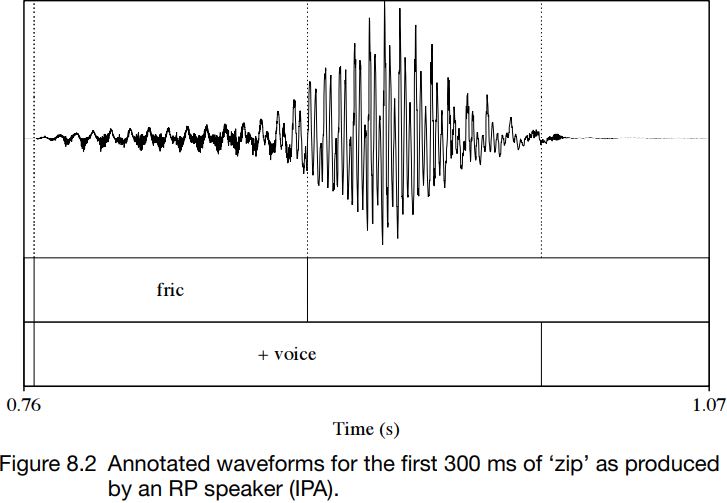

Figures 8.1 and 8.2 show waveforms of a stretch of about 300 ms from the words ‘sip’ and ‘zip’ as produced by a speaker of RP in isolation. In these figures, friction and voicing are marked. As can be seen, for ‘sip’, the initial friction and voicing do not overlap at all: the waveform has no periodicity until after the aperiodic friction has ended. By contrast, in the case of ‘zip’, friction and voicing overlap throughout the period of friction. The waveform contains signs of aperiodic and turbulent airflow; and superimposed on it can be seen a low-amplitude, regular, periodic waveform, which indicates vibration of the vocal folds.

Other differences are visible too. The friction in ‘sip’ lasts about twice as long as the friction in ‘zip’. (The graphs are shown on the same scale, with marks on the x-axis every 100 ms.) The friction for ‘sip’ is also louder, which can be seen in the vertical displacement in the waveforms. These differences in duration and amplitude are consistently found in the pairs  , even though the alignment of voicing and friction is highly variable.

, even though the alignment of voicing and friction is highly variable.

Figure 8.3 shows a spectrogram of ‘sip’ and ‘zip’ as produced in Figures 8.1 and 8.2.

The differences that have already been mentioned can be seen here too. [s] and [z] have turbulence centred at 4000 Hz and above. For [z], voicing can also be seen below 1000 Hz. The duration of friction is much longer in ‘sip’ (between about 0.05 s and 0.3 s on the spectrogram) than in ‘zip’; and it is louder, which means it appears as darker on the spectrogram.

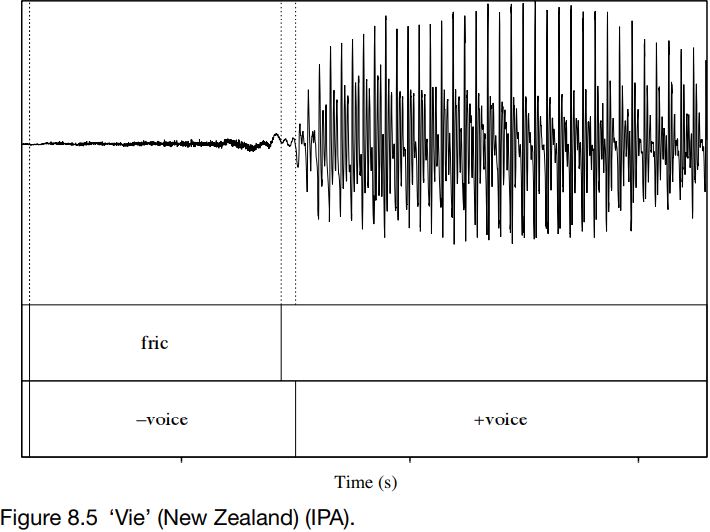

Now by way of contrast let us look at a similar pair, also citation forms, as spoken by a New Zealander. This speaker often produces the fricatives transcribed as  without vocal fold vibration, but the other differences are still found – the amount of friction noise produced is lower for

without vocal fold vibration, but the other differences are still found – the amount of friction noise produced is lower for  , and the duration of the frication is shorter.

, and the duration of the frication is shorter.

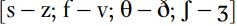

Figures 8.4 and 8.5 show productions of ‘fie’ and ‘vie’ by a New Zealander. For ‘fie’, as expected, friction is produced without voicing. But the same is true for ‘vie’, where voicing and friction do not coincide. This is unexpected, and we might assume that ‘fie’ and ‘vie’ are homophones for this speaker. But they are not: as can be seen from the vertical displacement in the waveforms, [f ] is produced louder – with more turbulent friction – than [v]; and at about 145 ms the friction for [f ] is longer in duration than that for [v], which is about 110 ms. These productions of voiced fricatives, where there is little or no voicing along with friction, are very common in English, so we will look at them in a bit more detail.

Figure 8.6 shows a spectrogram of the utterances in Figures 8.4 and 8.5: note the lower-amplitude friction for [v] than for [f ]: between about 0.1 and 0.2 s the fricative portion corresponding to [f ] on the spectrogram is darker than the corresponding portion between about 0.8 and 0.9 s, which corresponds to [v].

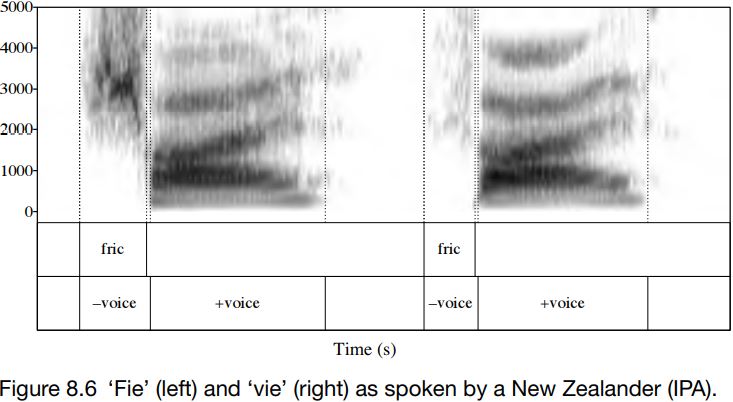

These patterns of partial voicing are recurrent in English. On first noticing them, it is common to worry about how to name and transcribe these differences. There are a number of solutions to this problem. First, the difference has often been referred to as ‘tense’ [f θ s ʃ] and ‘lax’  (rather than ‘voiced’ and ‘voiceless’), to avoid the implication that

(rather than ‘voiced’ and ‘voiceless’), to avoid the implication that  are necessarily accompanied by regular vocal fold vibration. This is not a solution that has been universally accepted, because it can be seen as just a difference in the way names are used, and is not much more descriptive or factually accurate than the term ‘voiced’. Secondly, conventions should be stated for transcription symbols so that they can be interpreted accurately. The details are set out in Table 8.2.

are necessarily accompanied by regular vocal fold vibration. This is not a solution that has been universally accepted, because it can be seen as just a difference in the way names are used, and is not much more descriptive or factually accurate than the term ‘voiced’. Secondly, conventions should be stated for transcription symbols so that they can be interpreted accurately. The details are set out in Table 8.2.

We may want to represent the overlap of friction and voicing more accurately in our transcriptions: for instance, there may be variability within a speaker’s productions so that some instances of  are fully voiced while others are not. In this case, we might transcribe

are fully voiced while others are not. In this case, we might transcribe  , but use the diacritic for ‘voiceless’,

, but use the diacritic for ‘voiceless’,  , along with the symbol for ‘voiced’ fricatives:

, along with the symbol for ‘voiced’ fricatives:  . These symbols might seem to be equivalent to [f θ s ʃ], but conventionally they are thought of as implying lower-amplitude friction and shorter duration of friction, so that they do not refer to the same sounds as [f θ s ʃ].

. These symbols might seem to be equivalent to [f θ s ʃ], but conventionally they are thought of as implying lower-amplitude friction and shorter duration of friction, so that they do not refer to the same sounds as [f θ s ʃ].

By using this diacritic, we can transcribe three kinds of fricative, such as  . This does not represent the phonological facts of English, because there is no evidence that three kinds of fricatives contrast in any variety of English, but it may be that the distribution of

. This does not represent the phonological facts of English, because there is no evidence that three kinds of fricatives contrast in any variety of English, but it may be that the distribution of  and [z] is regular and patterned (e.g. related to location in syllable structure), and therefore the differences between them could be linguistically informative details.

and [z] is regular and patterned (e.g. related to location in syllable structure), and therefore the differences between them could be linguistically informative details.

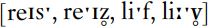

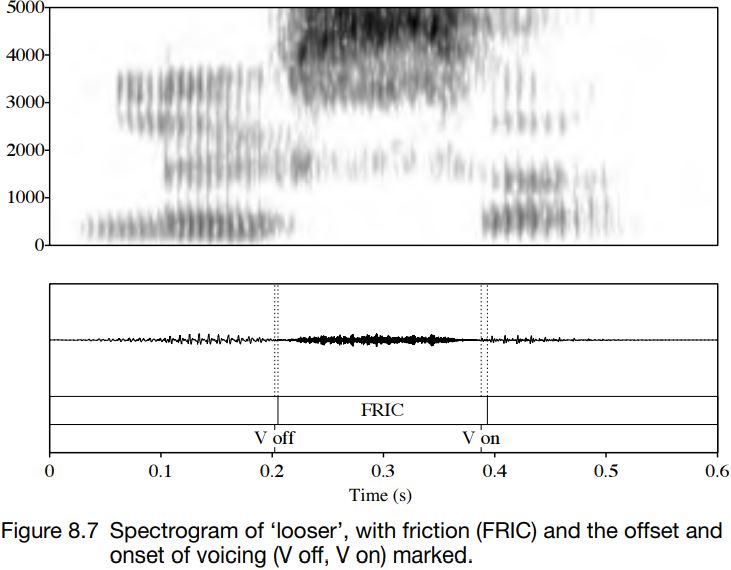

These differences are not true of medial fricatives. Typically, in a vowel + voiced fricative + vowel sequence, there is a short period of voicing and friction at the beginning and the end of the fricative portion, and the middle part of the fricative is often either voiceless or has only low-amplitude (quiet) voicing. Usually, there is a little more overlap of friction and voicing going into a fricative from a vowel than there is coming out of a fricative portion into a vowel. In either case, the period of overlapping friction and voicelessness is usually just a few cycles of voicing as the vocal folds stop (or start) vibrating. This can be seen in Figures 8.7 and 8.8: compare the duration of friction for the voiced and voiceless fricatives; the amplitude; and the point at which the voicing goes off (V off ) and on (V on).

If you compare words with voiceless and voiced fricatives finally, such as ‘race’ and ‘raise’, or ‘leaf ’ and ‘leave’, you will hear that although there is little or no voicing towards the end of the words with [z] and [v], the friction is quieter than in the words with [s] or [f ]:  . For many speakers of English, this reduction of friction noise as compared to their voiceless counterparts is one of the properties of the sounds

. For many speakers of English, this reduction of friction noise as compared to their voiceless counterparts is one of the properties of the sounds  . This reduction in friction noise happens even when the sounds are produced without voicing throughout, as when they are word final.

. This reduction in friction noise happens even when the sounds are produced without voicing throughout, as when they are word final.

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ينظم دورة عن آليات عمل الفهارس الفنية للموسوعات والكتب لملاكاته

|

|

|