Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-10-20

Date: 2023-10-13

Date: 2023-05-11

|

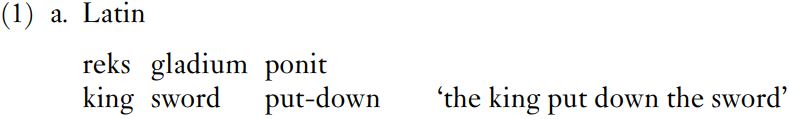

We have already discussed the category of case in various places, particularly on syntactic linkage where we looked at certain key facts of case in Latin, but also on grammatical functions and on roles. The term ‘case’ was traditionally used for the system of noun suffixes typical of Indo-European languages. For convenience, we reproduce as (1a) and (1b) below some of the Latin examples .

Gladium has the accusative suffix. Any adjective modifying gladium also has to be in the accusative case, as in (1b).

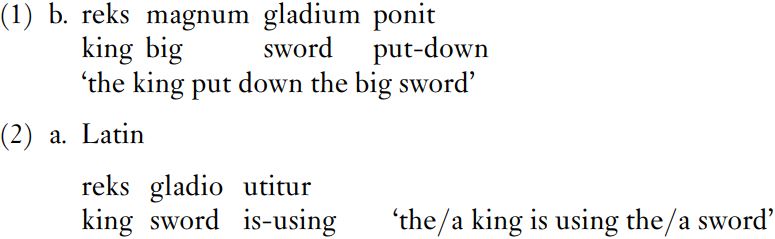

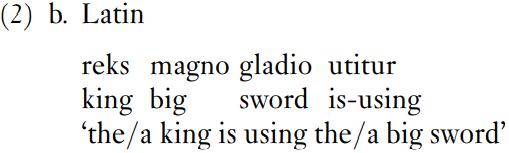

In (2), gladio has the ablative suffix -o. Any adjective modifying gladio also has to be in the ablative case, as in (2b), where magno is the ablative singular form of magn-.

As discussed, different suffixes are required for plural nouns – reges instead of reks, gladiis instead of gladio. Moreover, Latin nouns fall into three major classes and two minor classes, and each class has its own set of case suffixes. The case suffixes signal the relation between the nouns in a clause and the verb, and they signal which adjectives modify which noun and which noun modifies a given preposition (since different prepositions assign different cases). English does not have case suffixes. Pronouns display remnants of the earlier case system – saw me vs *saw I, to me vs to I – but no case suffixes are added to nouns, and there is no ‘agreement’ between a noun and the adjectives that modify it.

English does have the possessive suffix ’s in John’s bike and Juliet’s spaniel. In spoken English, with the exception of irregular nouns such as children or mice, ’s is not added to plural nouns. Possession is signaled (in writing) by an apostrophe added to plural nouns, as in the dogs’ kennel. The apostrophe has no spoken equivalent. The ’s suffix is also added to noun phrases rather than nouns, as in the woman next door’s poodle and John and Juliet’s garden. An analysis of the possessive suffix goes beyond the scope of this book, but it is clear that it behaves very differently from the case suffixes of languages such as Latin and Russian.

As explained in on roles, the traditional concept of case has been extended to take in the relationships between verb and nouns in clauses and the ways in which these relationships are signaled. In some languages, the relations are marked by affixes added to the verb, but these would still come under the modern concept of CASE. (It will be helpful to use capital letters when referring to the modern extended concept and small letters when referring to the traditional concept or to affixes or, as in English, to prepositions.) CASE is relevant to English; the relations between verb and nouns in clauses are signaled by position and by the presence or absence of prepositions. In the basic active declarative construction, the subject is to the left of the verb, with no preposition, and the direct object is to the right of the verb, with no preposition. In the indirect object construction, the indirect object is immediately to the right of the verb and followed by the direct object. All other nouns in a clause are connected to the verb by a preposition. (Note that this does not mean that all prepositions signal verb–noun relations. They can also signal noun–noun relations, as in the vase on the table, and adjective–noun relations, as in rich in minerals.) The key question is to what extent any constant meaning attaches to a given preposition wherever it occurs (and, for languages such as Latin and Russian, the extent to which a constant meaning attaches to a given case suffix).

|

|

|

|

"عادة ليلية" قد تكون المفتاح للوقاية من الخرف

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ممتص الصدمات: طريقة عمله وأهميته وأبرز علامات تلفه

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ضمن أسبوع الإرشاد النفسي.. جامعة العميد تُقيم أنشطةً ثقافية وتطويرية لطلبتها

|

|

|