تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

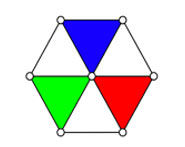

الهندسة

الهندسة

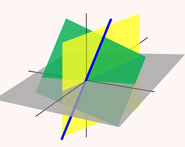

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 31-3-2016

Date: 30-6-2016

Date: 27-3-2016

|

Born: 1700

Died: 30 July 1762 in London, England

William Braikenridge was an Anglican clergyman who worked on geometry and discovered independently many of the same results as Maclaurin. In [1] he is described as follows:-

Braikenridge was a noted theologian and for many years he was rector of St Michael's Bassishaw, London. On 6 February 1752 he was elected fellow of the Royal Society of Antiquarians and on 9 November of the same year he became a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Braikenridge is well known for his geometrical theorems, in particular he discovered the following theorem now called the Braikenridge - Maclaurin theorem:-

If the sides of a polygon are restricted so that they pass through fixed points and all the vertices except one lie on fixed straight lines, the free vertex will describe a conic or a straight line.

This theorem appeared in Exercitatio geometrica de descriptione linearum curvarum published in 1733 but there followed a dispute regarding priority with Maclaurin. Braikenridge claimed to have discovered the theorem, and many other results, in 1726 when he was living in Edinburgh and that Maclaurin had learnt of them. An argument followed and the correspondence is preserved, see [2] where the letters are given and [4] for a discussion of the argument.

This was a rather sad affair and one has to feel sorry for both Braikenridge and Maclaurin but it is an affair that is worth expanding on since in many ways this is the main way in which Braikenridge enters the history of mathematics. The preface of Braikenridge's Exercitatio geometrica which was published in 1733 contained the following account of his interaction with Maclaurin:-

In the year 1727, during a three months stay in London I shared these thoughts with the celebrated gentleman J Craig, a very expert mathematician. After a few days it happened that I visited Colin Maclaurin, Edinburgh Professor, who at that time was visiting London, who recalled his conversation with Craig who had described my theorems, and [Maclaurin] said moreover that he had discovered similar ones and he showed me manuscripts which he said contained his own discoveries; but I am ignorant of the method he used for he did not entrust the manuscript to my hands, nor was I allowed to glance over it.

In a letter which Maclaurin wrote to John Machin on 15 November 1732, he gave his version of events (see for example letter 138 in [2]):-

[Braikenridge] taught mathematics here [in Edinburgh] privately for some years, and some time ago (viz. 1727) mentioned to me some theorems he had on that subject, which at the same time I showed him in my papers. Some time before that, he showed me a theorem, which coincided with one in my book, though he seemed not to have observed that coincidence. Coincidence: and indeed methods of this kind are often found coincident, that do not appear such at first sight. ... I find it is fit that I should take precautions, lest any forward person should take it in his head afterwards to say that I take these things from him, which I may have had long before him. And, therefore I shall send you an abstract of what I have done in relation to this matter, since the year 1719.

There then follows a fairly detailed description by Maclaurin of his results. Near the end of his letter to Machin, Maclaurin wrote:-

The author of the papers [i.e. Braikenridge] given in to the Royal Society will not refuse, that I showed him the theorems I now send you, in 1727. He owned [up to] it last summer at least.

Maclaurin did not dispute the fact that Braikenridge had published first; what did annoy him was the fact that he had been teaching courses at Edinburgh since 1725 which had contained these results yet he felt that Braikenridge was suggesting that he [Maclaurin] had not known of the results since he had not published them. Maclaurin asked for his 15 November 1732 letter to Machin to be published, and it appeared in December 1735 in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. On 15 January 1737, Braikenridge, who had seen the published version of Maclaurin's letter to Machin, wrote to Maclaurin (see for example letter 149 of [2]):-

... there are some people who pretend to be your friends represent you in a very odd light as if you was so unfair as to say that I took the theorems from you that I published in the "Exercitatio geometrica" which you know very well that I do not.

After quoting from his own Latin Preface to the Exercitatio geometrica of which we gave an English translation above, Braikenridge continues:-

After this account therefore you may be sure I never can deny that you showed me the paper in which your theorems were, neither can you deny that you never let me have the manuscript into my hand. And therefore as I have made so fair a declaration to your honour by giving my reader to understand that you had the like theorems; I hope you will likewise say what is true with regard to mine.

All this seems such an unfortunate misunderstanding and we have no reason to believe that either mathematician stole theorems from the other, both clearly discovering similar results independently. However, Braikenridge does then go on to attack Maclaurin's letter to Machin more violently. In particular he attacks Maclaurin's sentence "The author of the papers ... will not refuse, that I showed him the theorems ... in 1727" saying this suggests that:-

... either you let me read over your manuscript or that I had borrowed it from you or that you let me read some of your demonstrations, or at least that you let me see something in it that I did not know before ...

Braikenridge attacks even more vigorously Maclaurin's apparently innocent comment that Braikenridge taught mathematics in Edinburgh privately for some years:-

If this was only meant as a piece of innocent history to show that you were at that time in a more exalted position than I was, this is very well and I have nothing to say. But if as your friends here say you did it to insinuate the second-hand way by which I might possibly have taken your theorems from you, this deserves a more severe reflection than at present I think proper to make.

Braikenridge then says that indeed he did get some of the ideas from reading the work of others but that it was not Maclaurin's work, but rather it was the work of de la Hire that inspired him. Maclaurin composed a long letter in reply to Braikenridge, then decided not to send it. Rather he sent a short letter requesting that the correspondence come to an end:-

... after reflecting on your scurrilous manner of writing to me who never gave you any ground for such unaccountable usage, I cannot help desiring that your correspondence and mine be at an end.

Other works published by Braikenridge in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society include A general method of describing curves, by the intersection of right lines, moving about points in a given plane. Also Concerning the method of constructing a table for the probabilities of life in London, a work involving probability and statistics, as did two other works Concerning the number of people in England and Concerning the present increase of the people in Britain and Ireland. A further work on geometry was Sections of a solid hitherto not considered by geometers.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مستشفى العتبة العباسية الميداني في سوريا يقدّم خدماته لنحو 1500 نازح لبناني يوميًا

|

|

|