Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension| Reflection: Signifying in African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) |

|

|

|

Read More

Date: 27-5-2022

Date: 23-2-2022

Date: 4-5-2022

|

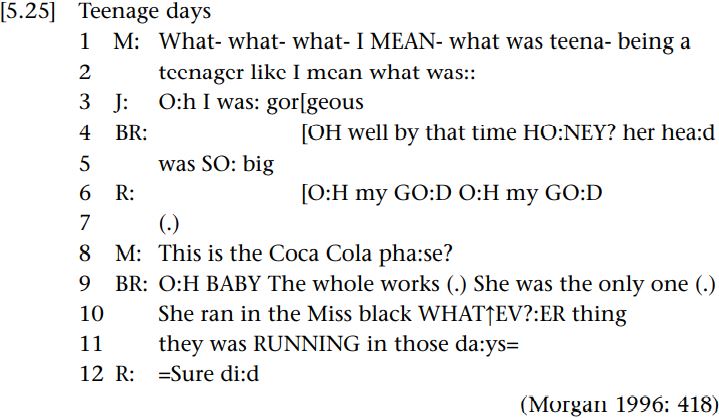

The term signifying is used by speakers of African American Vernacular English to refer to instances where the recognition of unsaid meaning is obscured by the ostensible content or function of what is said. Morgan (1996) focuses on two related practices of signifying:

Pointed indirectness: “when a speaker ostensibly says something to someone (mock receiver) that is intended for – and to be heard by – someone else and is so recognized”

Baited indirectness: “when a speaker attributes a feature to someone which may or may not be true or which the speaker knows the interlocutor does not consider to be a true feature” (Morgan 1996: 406)

While these two ways of signifying are not necessarily unique to speakers of AAVE, the ways in which they are accomplished as signifying involves resources particular to this variety of English. These include what is termed reading dialect, where lexical or grammatical features of AAVE are mixed in with mainstream American English in an obvious way: certain prosodic features, such as loud talking, high pitch and so on; and interactional features, such as gaze or parallelism in grammatical structures and word order. In the following excerpt from a conversation between African-American family members, including the researcher (Marcyliena) and three others (Judy, Ruby and Baby Ruby), we can observe some of these resources deployed in framing their talk as signifying on one of the participants, Judy. Marcyliena is Judy’s daughter, Ruby is Judy’s sister, while “Baby Ruby” (her nickname) is Judy and Ruby’s niece.

This signifying episode is triggered by Judy’s response in line 3 to the researcher’s question about what it was like being a teenager at that time. Baby Ruby employs pointed indirectness, in line 4–5, by addressing the researcher, who is also Judy’s daughter, rather than Judy herself in the subsequent turn, and baited indirectness through a negative assessment that is directed at Judy, namely, being conceited (despite the fact that Judy probably had good reason to think she was beautiful). What makes this signifying on Judy rather than just simply teasing or mocking is indexed through a number of features of Baby Ruby’s, and subsequently Ruby’s, talk. These include AAVE lexical items and prosody that signal a negative assessment amongst African-American women, such as honey (line 4), which is “often used among women to introduce a gossip episode or an unflattering assessment”, and baby (line 9), which “can imply a negative assessment as well as address those present” (ibid. 420). The concessive noun phrase “whatever” also functions as a negative quantifier of “thing” (line 10), which in this case in AAVE refers to an “attitude, belief or life”. In other words, it means something like “whatever fi t her ego” (ibid. 420). Finally, Judy’s silence also confirms that signifying has occurred here, since any response would only confirm Baby Ruby’s negative assessment, thereby treating the baited indirectness as true. We will revisit the issue of mocking in other varieties of English in our discussion of impoliteness.

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ينظم دورة عن آليات عمل الفهارس الفنية للموسوعات والكتب لملاكاته

|

|

|