Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Pragmatic Meaning Meaning beyond what is said

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

83-4

4-5-2022

841

Pragmatic Meaning

Meaning beyond what is said

We mainly focused on information and how it is packaged as more or less prominent within sentences. We will move on to consider another key area of interest in pragmatics, namely, how we can mean much more than we say or express. We also start to move beyond a focus on sentence-level to a consideration of meaning as it arises in talk exchanges.

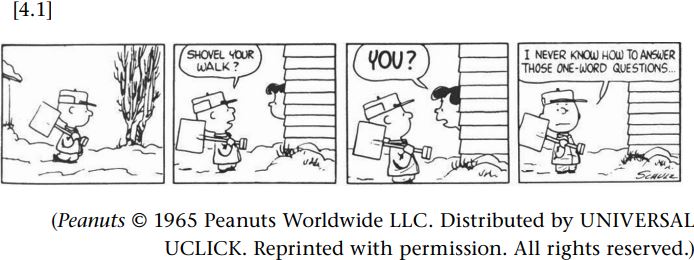

Consider example [4.1] from the comic strip Peanuts.

While Lucy responds with just one word here, it is clear that she means something else in addition to what she has said. More specifically, she implies that she doesn’t want Charlie Brown to shovel her walk (evident from the fact that she closes the door and so does not take up his offer), and perhaps also that Charlie Brown is somehow unsuitable for the task. The latter implication is in part indeterminate in that we do not know for what reason Lucy thinks Charlie Brown is unsuitable for shoveling snow (e.g. he is too weak, too incompetent, unlikely to finish and so on) and, moreover, just how certain she is about this evaluation. But it seems fair to say that Lucy has indeed meant something beyond what she has said here, namely, some kind of negative evaluation of Charlie Brown’s suitability for the task, and a refusal of his offer. We know this intuitively because her answer invites an inference in order to count as an adequate answer to Charlie Brown’s question, and also because we know (if we read Peanuts comics) that Lucy is always putting Charlie Brown down, and her behavior here is consistent with that. The former involves some form of pragmatic inferencing in order to figure out what counts as an adequate answer, while the latter arises through the kind of knowledge-based associative inferencing we briefly discussed. Pragmatic meaning thus involves content that is not straightforwardly expressed by the words someone utters but rather arises through some kind of inferencing, and so can be broadly characterized as meaning beyond what is said.

In pragmatics, just as in semantics, we generally conceptualize such meanings in terms of cognitive representations. A representation is essentially a generalized meaning form or interpretation that we find displayed in or through natural language constructions. Meaning representations are important because they are usually held to have considerable theoretical significance. An important foundational claim in pragmatics made by H. P. Grice (1967, 1989), a British-educated philosopher of language, is that meanings like the ones above, which go beyond what is said, can be broadly classified as speaker-intended implicatures, that is, meanings that are implied or suggested rather than said. He further proposed that what is implicated, either by a speaker or an utterance, can be contrasted with what is said. This distinction between what is implicated (cf. implying) and what is said (cf. saying) lies at the core of almost all of the subsequent attempts at theorizing about meaning representations in pragmatics, even those which have moved radically beyond it. We will thus start here by outlining Grice’s claims in more detail, before turning, in the latter sections, to the more fi ne-grained distinctions of pragmatic meaning that have since been proposed.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)