تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 18-1-2017

Date: 17-1-2017

Date: 22-1-2017

|

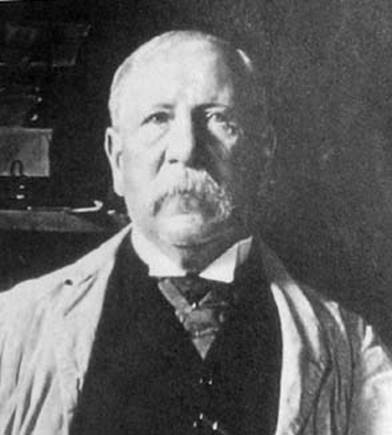

Died: 10 February 1927 in London, England

George Greenhill's father was Thomas Greenhill (born in Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire about 1811) who was a surveyor. His mother was Louisa Greenhill (born in Oxford, Oxfordshire about 1811). He had two older sisters: Louisa (born about 1844) and Mary (born about 1846) and two younger brothers Henry (born about 1849) and Edmund (born about 1851).

George Greenhill attended Christ's Hospital School, where he was awarded a Thompson Mathematical Gold Medal, and from there he went up to St John's College, Cambridge in 1866. There he won numerous scholarships being Pitt Club exhibitioner, then Somerset exhibitioner, then foundation scholar, then London University scholar, and finally Whitworth engineering scholar. He was placed Second Wrangler in the final examinations of 1870 and shared the Smith's Prize with the First Wrangler, R Pendlebury.

In the year of his graduation he was elected to a fellowship at St John's College. After a short time as Professor of Applied Mathematics at the Royal Indian Engineering College, Coopers Hill, Greenhill returned to Cambridge in 1873, becoming a fellow and lecturer at Emmanuel College. It is said that he left the Royal Indian Engineering College since [1]:-

... under the martial regime of Chesney, who was at that time President, Greenhill's independent spirit was ill at ease.

In 1876 Greenhill was appointed professor of mathematics at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. He held the chair there until he retired in 1908.

Greenhill's work was mainly on elliptic functions. He was interested in their applications to dynamics, hydrodynamics, elasticity, and electrostatics. As might be imagined given that Greenhill spent most of his life working in a military establishment, his work was often directed towards applications to ballistics and other military applications. Love, writing in [2], explains applications of the theory of the motion of a solid in a fluid made by Greenhill in 1879:-

Greenhill applied this theory to give an account of the steadiness of flight conferred upon an elongated projectile by rifling. He determined the least angular velocity about its axis for which steady motion of a solid of revolution can be stable. ... This practical application of what was regarded as a recondite mathematical theory earned for him much renown at Woolwich.

An important contribution Greenhill made to the theory of elasticity was his study of the greatest length that a cylinder can have before it bends under its own weight. His applications included computing the maximum height a tree can grow.

As well as his original research, Greenhill wrote several excellent texts and encyclopaedia articles. Among these books were Differential in integral calculus (1886), The applications of elliptic functions (1892), Treatise on hydrostatics (1894), Notes on dynamics (1908), Theory of stream lines with applications to an aeroplane (1910), Dynamics of mechanical flight (1912), and Gyroscopic theory (1914). In 1922 he headed a team preparing a table of elliptic functions.

Greenhill's approach to mathematics is summed up by Love [2]:-

The chief characteristics of Greenhill's work were a desire for concrete realisation of abstract theories and the direction of investigation to the solution of definite problems. Hence he valued applications of analysis above the analysis itself, and was led to work out minutely the details of multitudes of special cases. He was above all things a problem solver, but, to interest him, a problem had to be a real problem about material things and the ways in which they behave.

His rooms at Staple Inn, where he lived towards the end of his life, are described in [1]:-

There, with his books around him, his tables covered in neat disorder with innumerable scraps of material and apparatus to be used as dynamical models, his walls festooned with every variety of pendulum, simple or compound, contrived from articles purchased below a prescribed limit of cost at the local stores, upon his floor the treasured roll of Turkish carpet from his room of long ago at St John's, and above the mantelpiece the portrait of his beloved teacher, Clerk Maxwell, smiling approval - with all these and the precious memories they recalled, the scholar was content.

Love describes Greenhill's character and interests outside mathematics [2]:-

... he was keenly interested in antiquities, and had a profound knowledge of the antiquities of London. ... he had a considerable knowledge of music, and was a quite respectable performer on the organ and other instruments. He spoke French rather well, and read German easily. ... he was a sociable recluse, delighting especially in the conversation of people with tastes similar to his own.

In [1] he is described as follows:-

There was in his character a sense of humour, kindliness, and light-heartedness, but it was too often rendered bewildering by his eccentricity. It is related that as far back as the seventies he astonished his two professional companions in a walking tour of Surrey by setting out in silk hat and frock coat, his night attire being carried in a cardboard box. His friends knew that in general conversation it was best to avoid asking him a direct question. Inquiries about his health were responded to either by silence or by an expression of annoyance, real or feigned ... To the question of whether he would take tea or coffee his reply was a simple affirmative ...

Greenhill received many honours for his work. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1888, he won the De Morgan Medal of the London Mathematical Society in 1902 and the Royal Medal of the Royal Society in 1906. He served on the Council of the Royal Society and as President of the London Mathematical Society. He was knighted in 1908 on his retirement.

Articles:

|

|

|

|

"عادة ليلية" قد تكون المفتاح للوقاية من الخرف

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ممتص الصدمات: طريقة عمله وأهميته وأبرز علامات تلفه

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم التربية والتعليم يكرّم الطلبة الأوائل في المراحل المنتهية

|

|

|