تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 8-12-2016

Date: 22-12-2016

Date: 22-12-2016

|

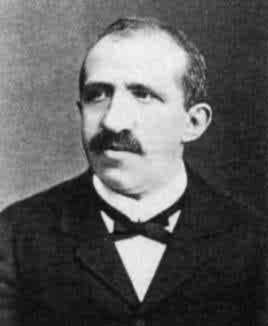

Died: 15 December 1921 in Heidelberg, Germany

Leo Königsberger came from a rich Jewish family, his father Jakob Löb Königsberger (1800-1882) being a wealthy merchant. Jakob had intended to study medicine but on the death of his own father, Leo's paternal grandfather, he had to take over a major manufacturing business to support his mother and siblings. Leo's mother Henriette Kantorowicz (1810-1895) had poor health but devoted herself to the education of her children. Leo was the oldest of his parents twelve children, four of whom died at a young age. It was in the family's beautiful and spacious house in the market square of Poznan that Leo grew up.

After attending primary school where he learnt to read, write, and do arithmetic, Leo entered the Friedrich-Wilhelms Gymnasium in Poznan. There he was taught elementary mathematics and science by a teacher named Brüllow whose lessons were both rigorous and interesting. However, the political situation resulting from attempts to divide the Province of Poznan between Germany and Prussia at this time, led to high tensions between the German and Polish schools, disrupting the pupils' education. Fighting between the German Gymnasium students, to which Königsberger belonged, and those of the Polish Mary's Gymnasium were almost daily events. The Revolution of March 1848 saw Königsberger's father take him away from the school as troops entered the middle of the town. A bombardment of the town from the fortress began and Jakob Königsberger decided to take his family away to live with an uncle until the situation had improved. In the days before they left for Berlin by train, shots were fired from the fortress every night. The frightened women and children sat in the living room of the Königsberger home while the men, armed with revolvers and axes, guarded the door to the house. After two weeks in Berlin, the family returned to Poznan to find that the situation had become much calmer.

Lazarus Fuchs arrived in Poznan at Easter 1853 and lived for a year in the Königsberger home. Leo learnt a great deal from Fuchs, who acted as a tutor to him during this year, so that by the time Fuchs left at Easter 1854 to begin his studies at the University of Berlin, Königsberger's education was transformed. Before that he had struggled at school but, after Fuchs' tuition, he had learnt how to study mathematics independently from books so that he was able to study topics not covered by his school. They had spent the evenings reading books on differential calculus and analytical geometry, working at a table in a small sitting room which they shared. Fuchs had also given Königsberger a love for mathematics, so from this time on he knew that it was the subject he wanted to study. He graduated from the Gymnasium and entered the University of Berlin at Easter in 1857.

When Königsberger arrived at the University of Berlin, his friend and former tutor Fuchs was still an undergraduate there. The two shared a large variety of different homes in Berlin, for even after Fuchs graduated in 1858 he continued to live in Berlin and teach mathematics there. In his first semester at the university, which was in the year 1857, Königsberger was taught by Karl Weierstrass who had been appointed to the University of Berlin in the previous year. In fact Königsberger had been so well prepared for university study that he attended Weierstrass's lectures on the theory of elliptic functions (which was Weierstrass's main research topic) and by the end of the course he was one of only four or five students who remained including Fuchs. Many years later, in 1917, he published his account of these lectures. This was the first course that Weierstrass gave on elliptic functions and Königsberger's publication was of considerable historical importance. Königsberger also attended lectures by Eduard Kummer, who had been appointed to Berlin two years before Königsberger began his undergraduate studies. Among Kummer's courses that he attended were higher number theory, the theory of surfaces, mechanics, and analytical geometry. Königsberger notes in [2] that Kummer attached:-

... more importance to the elementary parts of these disciplines, but with unmatched clarity to his listeners ...

Königsberger was given a research topic by Weierstrass. He submitted his doctoral thesis De motu puncti versus duo fixa centra attracti and was given an oral examination on 22 May 1860. In addition, he was given a mathematics examination by Martin Ohm and Eduard Kummer, a physics examination by Heinrich Gustav Magnus, and a philosophy examination by Friedrich Adolf Trendelenburg. After graduating with a doctorate from the University of Berlin with 'distinction', he qualified as a gymnasium teacher and spent the three years from Easter 1861 to Easter 1864 teaching mathematics and physics to the Berlin Cadet Corps. He writes [2]:-

As I had to give four or five lessons to the Cadet Corps every day, as well as carefully prepare the physics experiments, and in addition I was forced to give private lessons, so it was mainly in the evening and night hours that I carried out my mathematical researches.

In 1864 he obtained his first academic appointment as an extraordinary professor at the University of Greifswald, recommended for the position by Weierstrass. Although the salary he was offered was low, he did not hesitate to accept for the honour of receiving such an appointment. However, his long standing friendship with Fuchs made him sad to think that the two would now be separated. Five years later he was appointed to a chair of mathematics at Heidelberg. On leaving Greifswald, the students presented him with a beautifully bound edition of the first four volumes of Gauss's works to show their appreciation. While a professor in Heidelberg he had married Sophie Beral-Kappel (1848-1923) on 13 August 1873 in Baden-Baden with Bunsen and Kirchhoff as witnesses; they had two children one son Johann and one daughter Ani. Johann Georg Königsberger (1874-1946) went on to become professor of physics at the University of Freiburg, being mainly interested in electrical, optical and thermal properties of minerals.

In April 1875 Leo Königsberger left Heidelberg and moved to the Technische Hochschule in Dresden. This was not a move he really wanted to make so when he received the offer his first thought was to reject it. However, he felt that he had a duty to his wife to improve his situation so, with great sadness at leaving his friends and colleagues Bunsen and Kirchhoff, he accepted. He moved into a nicely situated house in fine surroundings and was settled in by the time lectures were due to start [2]:-

My lectures on differential and integral calculus, mechanics, etc. were held in new magnificent rooms with many students attending. I had time for extensive scientific work, including completion of the second part of my work on elliptical functions.

After two years in Dresden, Königsberger moved again, this time to the University of Vienna at Easter 1877. He returned to Heidelberg in 1884. After accepting the position in Heidelberg he travelled with his wife and two children to visit his mother, and then to visit his sister who was married and living in Russia. After these visits they spent two weeks holiday in the Crimea, relaxing in the beautiful seaside resort of Yalta.

From 1884 he taught in Heidelberg until he retired in 1914. So from an academic career spanning 50 years, despite the many moves, Königsberger spent 36 of these years at the University of Heidelberg. Returning to Heidelberg in 1884 was not easy after being away for seven years for during this time much had changed. The University of Heidelberg celebrated the 500th anniversary of its foundation in 1886. This was a particularly happy time for Königsberger who was joined by Hermite, Fuchs, Helmholtz, Bunsen, Roscoe, Brioschi and other friends from the world of mathematics and science. In the summer of 1889 there was a scientific meeting in Heidelberg at which Königsberger met Heinrich Hertz for the first time. Hertz had, shortly before, announced his famous discoveries which were causing great excitement in the scientific community. Königsberger entertained Hertz, Helmholtz, Kundt, Paalzow, Wiedemann and others to lunch in his home. This was also the year that he had a new house built in the Kaiserstrasse specifically designed to meet his wishes. He lived in this home for the rest of his life.

At Heidelberg, Königsberger was supported by some other excellent teachers. In particular the mathematical historian Moritz Cantor worked there for most of his career, beginning in 1853, while Georg Landsberg, whom Königsberger described as an "inspiring teacher," taught at Heidelberg between 1893 and 1904.

Burau sums up Königsberger's contributions in [1]:-

Königsberger was one of the most famous mathematicians of his time, member of many academies, and universally accepted. He contributed to many fields of mathematics, most notably to analysis and analytic mechanics.

His early work was heavily influenced by his teacher Weierstrass's lectures on elliptic functions, for this was the topic of much of his early research. He wrote an important text on elliptic functions Vorlesungen über elliptische Funktionen in 1874 and another important textbook on hyperelliptic integrals Vorlesungen über die Theorie der hyperelliptischen Integrale four years later. Much of Königsberger's work on differential equations was influenced by the function theory developed by his friend Fuchs. His work on differential equations was, however, also influenced by the applications which interested Bunsen, Kirchhoff and Helmholtz, with whom he was close friends in Heidelberg. His approach to the differential equations of analytic mechanics showed novelty [1]:-

Königsberger was the first to treat not merely one differential equation, but an entire system of such equations in complex variables.

On this topic he published Lehrbuch der Theorie der Differentialgleichungen mit einer unabhängigen Veränderlichen in 1889. Königsberger writes [2]:-

In 1889 I published 'Lehrbuch der Theorie der Differentialgleichungen', which is a coherent presentation of my previous work extending that of Weierstrass, Fuchs and Poincaré. ... My further work led me now more and more into analytical mechanics, and I published in mathematical journals and in the proceedings of various academies a greater number of articles dealing with the extension of the principles of mechanics and potential theory ...

Königsberger is also famed for his two volume biography of Helmholtz (1902) and his biographical Festschrift for Jacobi (1904).

Books:

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتبة أمّ البنين النسويّة تصدر العدد 212 من مجلّة رياض الزهراء (عليها السلام)

|

|

|