النبات

النبات

الحيوان

الحيوان

الأحياء المجهرية

الأحياء المجهرية

علم الأمراض

علم الأمراض

التقانة الإحيائية

التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

علم الأجنة

علم الأجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

الأحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

الغدد

المضادات الحيوية

المضادات الحيوية|

Read More

Date: 10-3-2021

Date: 25-2-2021

Date: 9-12-2015

|

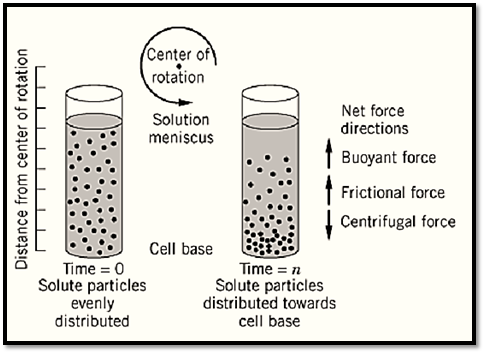

Centrifugation

Centrifugation is a technique often employed during isolation or analysis of various cells, organelles, and biopolymers, including proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and carbohydrates dissolved or dispersed in biologically relevant solvents (ie, typically aqueous buffers). It is also applicable to synthetic macromolecules dispersed or dissolved in nonaqueous, organic solvents. In this technique, the sample (comprising a liquid phase and a solute) is placed in a suitable vessel, and the vessel is spun in a centrifugal rotor. The centrifugal force created by the spinning rotor causes the solute sample to sediment out of solution (typically, though not always, toward the base of the vessel) (Fig. ( 1. The centrifugal force applied to the sample is akin to gravitational force (acceleration) and is measured in gravities, as in n × G (the gravitational constant G equals 6.6720 × 10–11 N-m2/Kg2). The extent to which the sample sediments toward the base of the vessel is a function of a series of complex interacting factors related to the properties of the solute alone and of the system as a whole (solvent and solute) (Fig. 1, Tables 1 and 2. (

Figure 1. A schematic diagram of a centrifugation experiment.

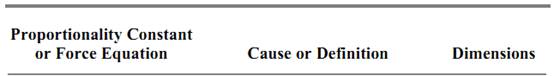

Table 1. The Forces Involved in Centrifugation

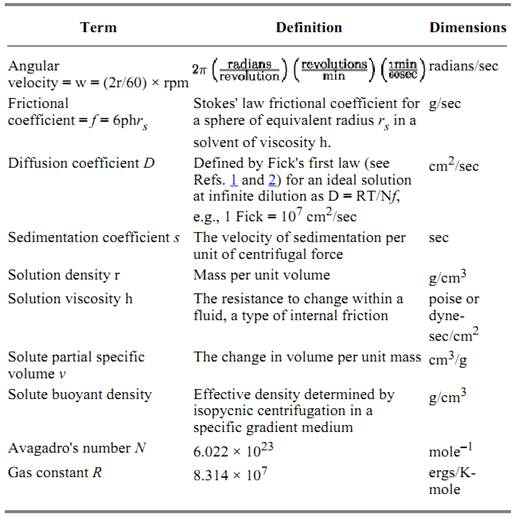

Table 2. General Proportionality and Descriptive Constants for Centrifugation

The factors that define the entire sedimenting system include (1) the rate w at which the rotor spins; (2) the length of time for which the centrifugal force is applied; (3) the solvent density r; and (4) the system temperature T. The factors specific to the sedimented solute include (1) the radial distance r of the solute from the central axis of rotation; (2) the solute partial specific volume v; (3) the solute diffusion coefficient D; (4) the solute frictional coefficient f; and (5) the solute sedimentation coefficient s . During centrifugation (Fig. 1), the centrifugal force is opposed by buoyant density and frictional forces. Under these conditions it can be shown that the rate of sedimentation of the solute molecules of weight-average molecular weight Mw and moving as a radial boundary rb is defined by

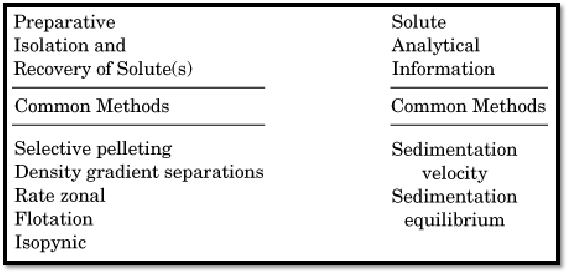

Operationally, the technique can be divided into preparative and analytical modes, which differ principally in whether the actual recovery of the materials that have been centrifugally separated is desired or practical (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Common preparative and analytical methods used in centrifugation.

1. Preparative Centrifugation and Ultracentrifugation

Preparative centrifugation (Fig. 2) is routinely employed in isolating, separating, and purifying a variety of biological and cellular/subcellular components. Some examples include chromatin, coated vesicles, cytosolic proteins, DNA, Golgi, inclusion bodies, lipoproteins, lysosomes, Microorganisms, Microsomes, mitochondria, myelin, nuclei, glycoproteins, RNA, Peroxisomes, plasma membranes, polysomes, proteoglycans, ribosomes, synaptosomes, and viruses. Preparative centrifugation has two primary modes of separation. Solutes can be selectively pelleted from solution, as described here, or they can be subjected to separation along a solution density gradient.

1.1. Selective Pelleting or Differential Centrifugation

Clearing macromolecular components from solution is probably the most commonly employed preparative centrifugation technique. In this method the sample is subjected to centrifugation, usually, though not necessarily, at a constant rotor velocity. Over time, a pellet of sedimented material is deposited along the most radially distant wall of the tube containing the sample (Table 3). At a sufficiently high rotor speed (and therefore high centrifugal force), virtually all macromolecular solute components heavier than the solvent are pelleted out of solution over time. Because it is possible to select a variety of rotor velocities, sample tube dimensions, rotor types, centrifugation run times, etc., it is often possible to accomplish a significant level of purification by pelleting alone because the method of separation relies on the differential sedimentation rates of small and large solute components. For example, large components are typically removed by sedimentation at low speeds for short periods of time. If the supernatant from such a centrifugation is placed in a new container and centrifuged again at a higher rotor velocity for an appropriate period of time, it is possible to collect another distribution of particles from solution, this time of smaller dimensions than the first. Therefore repeating this process yields a series of pelleted samples with distributions of solute molecules, each of which have accumulated under conditions differing only in their centrifugal forces and thus have different sedimentation rates. Most samples of biological interest are complex mixtures of interacting solutes in solution at widely different concentrations. Because the size, shape, and concentration distributions of these components are routinely broad, together they exhibit very broad distributions of sedimentation rates. Thus the technique of solute pelleting, though widely applied, is only rarely sufficient to purify a single component completely. Typically it is used to selectively enrich, often to a high degree, a preparation of cellular or subcellular components in a single component. For small biological solutes, such as soluble cytosolic proteins prepared by a protein isolation procedure, pelleting is routinely employed along with differential precipitation (salting out) using ammonium sulfate to yield highly enriched, sedimented precipitates of the desired protein components.

Table 3. Descriptive Constants for Preparative Centrifugation

Pelleting is also of great use when applied to harvesting viruses or cells from various growth media. When cells or viruses are used to produce various recombinant proteins of pharmaceutical interest, centrifugal harvesting is often employed to capture the biological component from the (usually large( fermentation broth. In these applications, a preparative centrifuge and rotor capable of accepting a continuous flow into and through the rotor are employed. The centrifugal force applied to the sample stream as it passes through the rotor is adjusted to permit selective pelleting of cells within the centrifuge rotor. The cell-depleted broth passes out of the rotor/centrifuge and into a receiver vessel, and, then the harvested cells are recovered from the centrifuge rotor.

References

1. K. E. Van Holde (1971) Physical Biochemistry, Prentice Hall, Englewood, Cliffs, NJ, pp. 70–121.

2. H. Fugita (1962) Mathematical Theory of Sedimentation Analysis. Academic Press, New York.

|

|

|

|

دخلت غرفة فنسيت ماذا تريد من داخلها.. خبير يفسر الحالة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ثورة طبية.. ابتكار أصغر جهاز لتنظيم ضربات القلب في العالم

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مشاهد ايمانية.. مرقدا الامام الحسين واخيه العباس (ع) يشهدان اكتظاظ حشود الزائرين لإداء مراسم صلاة عيد الفطر المبارك (صور)

|

|

|