Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods| A case study of the semantics of clear - The paradox of asserting clarity |

|

|

|

Read More

Date: 14-6-2021

Date: 2024-09-28

Date: 14-6-2021

|

A case study of the semantics of clear - The paradox of asserting clarity

The starting point for a semantic analysis of clear is to review the paradox of asserting clarity, as introduced in Barker and Taranto (2003). The paradox as it is presented here is faithful to the analysis in Barker and Taranto, but the formal semantics that is introduced, which takes as its starting point the model of context update proposed by Gunlogson (2001), is taken from Taranto (2006). The discussion in this chapter takes clear to be representative of the entire class of discourse adjectives.

The paradox of asserting clarity arises from the standard assumption in (1), namely that an assertion is felicitous only if it adds new information to the common ground.

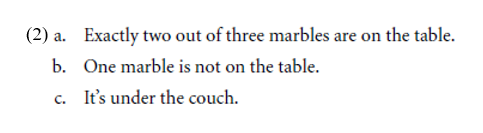

After all, what use could it be to claim that a proposition is true if it is already accepted as true? A possible answer is that some sentences can have side-effects besides adding new information about the world to the common ground, and it can be worth asserting a sentence entirely for the sake of these side-effects. To motivate this claim, consider the variation of Partee’s famous marble example in (2).

Sentence (2b) is entailed by (2a). It adds no new information about the situation under discussion. However, it does cause the creation of a discourse referent for the missing marble, which allows a pronominal reference in (2c). If (2b) were omitted from the discourse, it would be infelicitous to use the pronoun it in (2c). Thus, as pointed out in Beaver (2002), it is possible to assert a sentence purely for the sake of its side-effects, in this case, building a discourse referent to facilitate anaphora.

What will emerge in the discussion of the discourse adjective clear is that assertions of clarity are useful in establishing which propositions are genuinely in the common ground of a discourse and which are not. With this in mind, consider the core example for this chapter’s discussion of clear, the sentence in (3).

(3) It is clear that Briscoe is a detective.

Intuitively, if (3) is true, then before it is uttered, both the speaker and addressee must already believe that Briscoe is a detective. If either is not already convinced that Briscoe is a detective, then it is not clear at all. But if it was already evident that Briscoe is a detective, then asserting (3) adds no new information to the context, contra the assumption in (1). The question to ask, then, is what new information might an utterance of (3) provide?

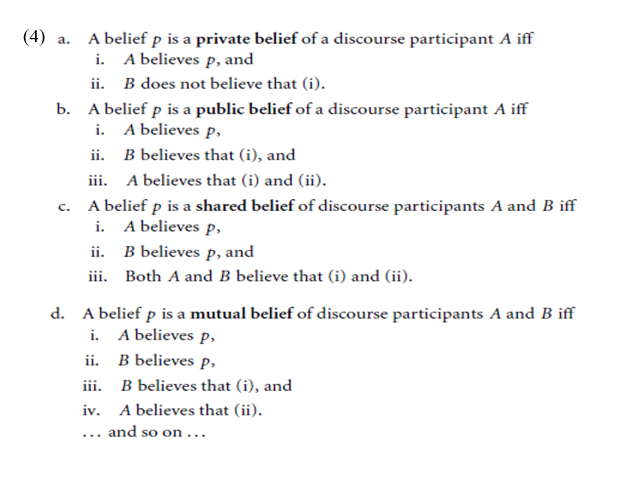

In order to address this question, it is necessary to distinguish between the different types of beliefs that individuals in a discourse may have. I propose the definitions provided in (4), which assume a conversation with exactly two participants, A and B.

|

|

|

|

مقاومة الأنسولين.. أعراض خفية ومضاعفات خطيرة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمل جديد في علاج ألزهايمر.. اكتشاف إنزيم جديد يساهم في التدهور المعرفي ؟

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تقيم ندوة علمية عن روايات كتاب نهج البلاغة

|

|

|