Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-09-28

Date: 2024-09-13

Date: 2024-09-16

|

Identifying the proper source of a supposed class grouping can be a terrific aid in helping you clarify your real message. Suppose you came across this:

The traditional financial focus of investment evaluation results in misleading prescriptions for corporate behavior:

1. Corporations should invest in all opportunities where probable returns exceed the cost of capital

2. Better quantification of future uncertainty and risk is the key to more effective resource allocation

3. Planning and capital budgeting are two separate processes -Capital budgeting is a financial activity

4. Top management's role is to challenge the numbers rather than the underlying thinking

Now apparently these four "misleading prescriptions" reflect commonly believed "rules of thumb" in corporations. But do they? If you reword them as results, they say, in abbreviated form:

The financial focus:

1. Encourages corporations to invest

2. Emphasizes quantification of uncertainty

3. Separates planning and capital budgeting

4. Leads top management to focus on the numbers

All but the third can now be seen as part of a process of decision making, which would dictate time order which in turn would lead to a clearer point at the top:

The traditional financial focus of investment evaluation can result in poor resource allocation decisions because it:

l. Emphasizes quantification of future uncertainty and risk as the key to choosing among projects

2. Leads top management to focus on the numbers rather than on the underlying thinking

3. Encourages investment in all opportunities where probable returns exceed the cost of capital, ignoring other considerations

That one was easy to sort out because the kind of idea you were dealing with was easy to identify simply by reading it. Very often, however you will find yourself with a longer list of ideas classified as “reasons" or "problems", obscuring the fact that it contains subclasses of varying kinds of reasons or problems. Remember this example from the introduction to this section:

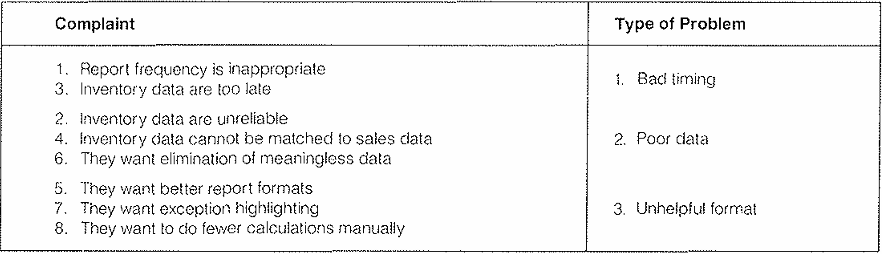

Buyers are unhappy with the sales and inventory systems reports

1. Report frequency is inappropriate

2. Inventory data are unreliable

3. Inventory data are too late

4. Inventory data cannot be matched to sales data

5. They want reports with better formats

6. They want elimination of meaningless data

7. They want exception highlighting

8. They want to do fewer calculations manually

The trick is to go through and sort them into rough categories, as a prelude to looking more critically. You get the categories by defining the kind of problem being discussed in each case. Thus, if "Report frequency is inappropriate," the type of problem indicated is "Bad timing," etc.

Now you see that the author is complaining about three types of problem with the reports: timing, data, and format. What order do they go in? That depends on whether you are talking about the process of preparing the report, the process of reading the report, or the process to follow in fixing the problem. In other words, the order reflects the process, and the process is dependent on the question being answered:

This example has demonstrated the only process I know for getting at the real thinking underlying lists of ideas grouped as a class.

1. Identify the type of point being made

2. Croup together those of the same type

3. Look for the order the set of groups implies.

Here is another example of the process in application:

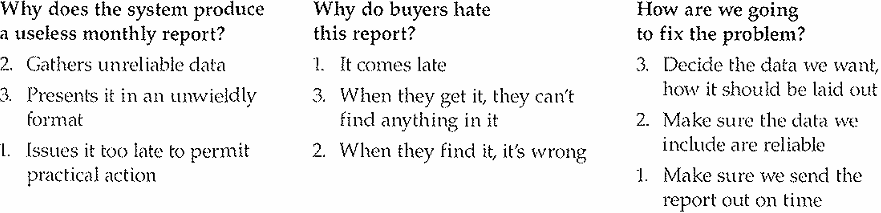

The causes of New York's decline are many and complex. Among them are:

I. Wage rates higher than those that prevail elsewhere in the country

2. High energy, rent and land costs

3. Traffic congestion that forces up transportation costs

4. A lack of modern factory space

5. High taxes

6. Technological change

7. The competition of new centers of economic concentration in the Southwest and West

8. The refocusing of American economic and social life in the suburbs

Again, this is just a list rather than a communication of thinking. But the process for getting at the underlying thinking does work. First, look for similarities.

Then look for order and the message. In this case it is probably order of importance:

The causes of New York's decline are easy to trace

1. High costs

2. Difficult working conditions

3. Attractive alternatives

To summarize, I have tried to demonstrate with all these examples that checking order is a key means of checking the validity of a grouping. With any grouping of inductive ideas that you are reviewing for sense, always begin by running your eye quickly down the list. Do you find an order (time, structure, degree)? If not, can you identify the source of the grouping and thus impose one (process, structure, class)? If you have a long list, can you see similarities that allow you to make subgroupings, and impose an order on those?

Once you know a grouping of ideas is valid and complete, you are in a position to draw a logical inference from it, as explained in: Summarizing Grouped Ideas.

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتبة أمّ البنين النسويّة تصدر العدد 212 من مجلّة رياض الزهراء (عليها السلام)

|

|

|