Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 17-3-2022

Date: 2024-07-06

Date: 2023-12-06

|

A political language issue in New Zealand is the pronunciation of Maori words when they are used in English. Broadly, we can sketch two extreme positions: (i) an assimilationist position, according to which all Maori words are pronounced as English, and (ii) a nativist position, according to which all Maori words are pronounced as near to the original Maori pronunciation as possible. There are, of course, intermediate positions in actual usage. Some of the variation is caused by the fact that the original Maori pronunciation may not be easily determinable. Not only is vowel length sometimes variable even in traditional Maori, in some cases the etymology of place names may be in dispute within the Maori community (Paraparaumu provides an instance of this, where it is not clear whether the final umu is to be interpreted as ‘earth oven’ or not).

Where vowels are concerned, the major difficulty in pronouncing Maori words with their original values is that vowel length (usually marked by macrons in Maori orthography, as in Māori) is rarely marked on public notices. Not only can this affect the way in which the particular vowel is pronounced, it can affect stress placement as well, since stress in Maori words is derivable from moraic structure. The reluctance to use macrons in public documents may simply be a typographical problem (even today with computer fonts easily available, very few newspapers or journals appear to have fonts with macrons available to them), but in the past has also been supported by the sentiments of Maori speakers who have found the macron unaesthetic. There may be good linguistic reasons for this, though they remain largely unexplored. The point is that although all vowels show contrastive length in Maori, long may be pronounced as short and short may be pronounced as long in English. Since Maori has no reduced vowels while English tends to reduce vowels in unstressed syllables (though this is less true of New Zealand English than it is of RP), almost any Maori vowel may be reduced under appropriate prosodic conditions. Where toponyms are concerned, there has also been a very strong Pakeha tradition towards abbreviating the longer names (a tradition which does not appear to spread to English names). For example, Paraparaumu is frequently called Paraparam, the Waimakariri river is called the Waimak, Wainuiomata is frequently called Wainui. While there is also a tradition for the abbreviation of names within Maori itself, and the two traditions may support each other to some extent, they appear to be largely distinct traditions with different outcomes. Pakeha abbreviations of toponyms are frowned upon within the nativist position on the pronunciation of Maori.

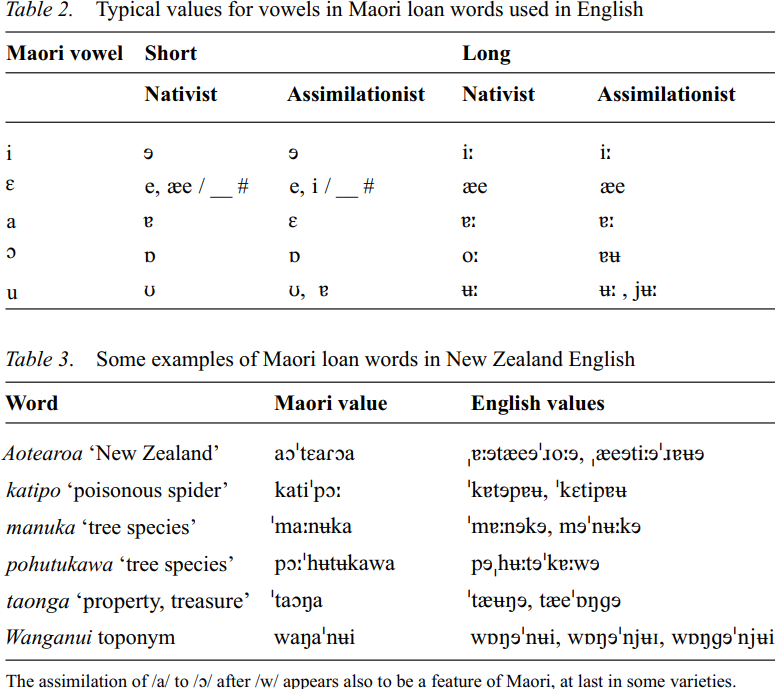

Table 2 shows a range of possible pronunciations of the individual vowels of Maori, assuming that length has been correctly transferred to English. Table 3 provides some typical examples with a range of possible pronunciations, going from most nativist to most assimilationist. Maori pronunciations are also heard, and these may be considered to provide instances of code-shifting.

Maori diphthongs and vowel sequences do not transfer well to English. Maori /aε/ and /ɔε/ are merged with Maori /ai/ and /ɔi/ respectively as English /ae/ and /oe/. Similarly Maori /aɔ/ and /au/ may not be distinguished in English. Maori /au/, which in modern Maori is pronounced with a very central and raised allophone of /a/, is replaced by  in nativist pronunciations (where it may merge with Maori /ɔu/), but by

in nativist pronunciations (where it may merge with Maori /ɔu/), but by  in assimilationist pronunciations. Because of the NEAR-SQUARE merger in New Zealand English, Maori /ia/ and /εa/ are not distinguished in English. Maori /εu/ is often transferred into English as

in assimilationist pronunciations. Because of the NEAR-SQUARE merger in New Zealand English, Maori /ia/ and /εa/ are not distinguished in English. Maori /εu/ is often transferred into English as  (presumably on the basis of the orthography). Vowel sequences are transferred to English as sequences of the nearest appropriate vowel, but often involve vowel reduction in English which would not be used in Maori.

(presumably on the basis of the orthography). Vowel sequences are transferred to English as sequences of the nearest appropriate vowel, but often involve vowel reduction in English which would not be used in Maori.

Most Maori consonants have obvious and fixed correspondents in English, although this has not always been so. Some early borrowings show English /b, d, g/ for Maori (unaspirated) /p, t, k/ and occasionally English /d/ for Maori tapped /r/: for example English biddybid is from Maori piripiri. The phonetic qualities of the voiceless plosives and /r/ are now modified to fit with English habits. However, Maori /ŋ/ is variably reproduced in English as /ŋ/ or as /ŋg/, especially when morpheme internal. Word-initial /ŋ/ is always replaced in English by /n/. The Maori /f/, written as <wh>, has variable realizations in English. This is partly due to the orthography, partly due to variation in the relevant sounds in both English and Maori: [M] is now rare as a rendering of graphic in English, and the /f/ pronunciation is an attempt at standardising variants as disparate as [f], [M], [ɸ] , [ʔw] . The toponym Whangarei may be pronounced /fæŋɐræe, fɐŋɘræe, wɒŋɘræe, wɒŋgɘræe/.

|

|

|

|

4 أسباب تجعلك تضيف الزنجبيل إلى طعامك.. تعرف عليها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أكبر محطة للطاقة الكهرومائية في بريطانيا تستعد للانطلاق

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مشاتل الكفيل تزيّن مجمّع أبي الفضل العبّاس (عليه السلام) بالورد استعدادًا لحفل التخرج المركزي

|

|

|