Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-04-24

Date: 2024-04-01

Date: 2024-03-12

|

ChcE has the same consonant phoneme inventory, and all the allophonic variants, of General Californian English (GCE). ChcE allo-consonantal variants occur in addition to GCE consonantal allophones, and these ChcE variants occur with greater or lesser frequency among different ChcE speakers.

The ChcE alveolar stops often have an apico-dental point of articulation (which is the corresponding place of articulation in Spanish). Additionally, like some other English vernaculars, but not GCE, ChcE variably articulates its interdental fricatives as apico-dental stops. In her study of Los Angeles ChcE, Fought indicates that Euro-American participants did not use apico-dental stops, while even “very ‘standard’ sounding ChcE speakers who used few or none of the ChcE syntactic features” were heard to use apico-dental stops (2003: 68). Still, regarding the use and frequency of this substrate-based feature, Santa Ana’s impressions corroborate Fought’s claim that some Los Angeles ChcE speakers used the apicodental stops “almost categorically” (2003: 68). It is often impossible to predict which ChcE speaker is bilingual and which is an English-speaking monolingual. This phonetic patterning again belies the commonplace view that ChcE pronunciation is merely a matter of Spanish-language transfer of ELLs.

Fought noted that for both GCE and ChcE, one variant of syllable-final voiceless stops is a glottalized form, which she describes as a tensing and closing of the vocal cords as the stop is closed orally. This is often called an unreleased stop. Fought remarks that the consonant pronunciation is often associated in ChcE with a preceding creaky voice vowel. A more pronounced version of this process that Fought observes is the complete substitution of the voiceless stop with a glottal stop. Finally, there is a rare ejective version in which the glottalized stop is pronounced with a sharp burst of aspiration.

The most studied consonantal process in ChcE is (-t, d), or final alveolar stop deletion (Santa Ana 1991, 1992, 1996; Bayley 1994, 1997; Fought 1997). By /-t, d/ deletion we mean the loss of final alveolar stops in the process of consonant cluster simplification, e.g. last week [læs wik]. There are other related simplification processes. One is assimilation of a consonant of the cluster, as in l-vocalization, e.g. old [od]. Another is the deletion of one of the consonants. There is also nasalization in English, in -nC clusters, e.g. want, [wãt] , or in the context of a following unstressed vowel, a nasal flap. Then there is vowel epenthesis to create a syllable boundary between adjacent consonants to preserve the segments and eliminate the cluster. Finally, a process that is related to epenthesis is reassignment of the final consonant to a following vowel-initial syllable. Santa Ana (1991) stated that these ChcE forms also occur in other English dialects. However, Chicanos may reduce clusters to a greater extent than many other dialects.

A related process that calls for study is the deletion of single consonants in final or syllable-final position. We concur with Fought’s impression that it occurs “more frequently than in any other English dialect”, particularly among older speakers (Fought 2003: 69).

Santa Ana (1991, 1996) reviewed multivariate analyses of the patterns of the workhorse linguistic variable (-t, d) for several U.S. dialects (Standard American, several African American English studies, a vernacular Euro-American dialect, and Puerto Rican English) to determine the similarity of ChcE to other U.S. English dialects. He found the basic structure is shared across these dialects, but ChcE reanalysis has created a distinctive variable that reveals its Mexican Spanish substrate influence.

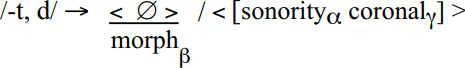

As a process operating in real time on the speech stream, many phonologists consider (-t, d) to be strictly a surface process, not a more foundational process (such as a Level-1 Process in models of Lexical Phonology). Santa Ana (1996) claimed otherwise, stating that the full range of conditioning effects on ChcE (-t, d) can be ordered in terms of the basic level concept of syllabification. He offered four generalizations. First, in ChcE, syllable stress is not a factor in deletion, which is a feature expected in stress-timed languages like English. Second, for both preceding environment and following environment, there is a correlation of the conditioning segment sonority to the frequency of deletion of the alveolar stop. An increase of the sonority of the preceding segment is correlated with increasing deletion. Conversely, a decrease of the sonority level of the following segment is correlated with an increase in deletion. Third, ChcE (-t, d) is correlated to [± coronal] place of articulation of the adjacent segment. Finally, regarding morphological categories, ChcE speakers attend to the regular past tense and past participle morphology of English, and tend to simplify alveolar stop clusters that carry this inflectional morphology at a very low rate. Santa Ana (1996) schematized ChcE (-t, d) as follows:

The alveolar stop variably deletes as conditioned by three rank-ordered constraints: the major constraint, or α, the sonority of the environment; β, the grammatical category of the word containing the /-t, d/ segment; and γ, the coronal value of the environment. The conditioning constraints are placed in angle brackets to indicate their variable values. A feature of the analysis not displayed in this schema is the contrary directions of the effect that sonority has on the /-t, d/, namely that increasing sonority of the preceding coda increases deletion while decreasing sonority of the following onset increases deletion. Fought (2003: 72) suggests the surprising absence of the syllable-stress factor in ChcE (-t, d) may be due to the syllable timed quality of the dialect, to which we turn.

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ينظم دورة عن آليات عمل الفهارس الفنية للموسوعات والكتب لملاكاته

|

|

|