النبات

النبات

الحيوان

الحيوان

الأحياء المجهرية

الأحياء المجهرية

علم الأمراض

علم الأمراض

التقانة الإحيائية

التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

علم الأجنة

علم الأجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

الأحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

الغدد

المضادات الحيوية

المضادات الحيوية|

Read More

Date: 29-10-2015

Date: 23-10-2015

Date:

|

Cell Evolution

Approximately 3.5 billion years ago, cellular life emerged on Earth in the form of primitive bacteria. Bacteria or “prokaryotes” organize their genes into a circular chromosome that lies exposed within the fluid environment of the cell. Within a billion years, bacterial cell types had flourished and diversified, evolving numerous ways of extracting energy from the environment. These types included first the fermenting anaerobic archaebacteria, then the oxygen-producing photosynthetic cyanobacteria, and finally respiring aerobic bacteria able to utilize the new oxygen-rich atmosphere. In addition some bacteria had become motile, such as the corkscrew-shaped wriggling spirochetes. All of these bacterial cell types have descendents living today.

Eukaryotes, whose deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is sequestered within a separate membrane-bound nucleus, first emerged perhaps 2 billion years ago. Eukaryotic cells also contain an extensive internal membrane system, a cytoskeleton, and different kinds of membrane-bound organelle, including mitochondria (the “power factories”) and, in algae and plants, plastids (sites of photosynthesis). All multicellular life, including plants, animals, and fungi, are composed of eukaryotic cells; some microbes, such as unicellular algae and protozoa, are also eukaryotes. So how did this great diversity of eukaryotic organisms evolve from prokaryotic ancestors?

Serial Endosymbiosis

The most widely accepted explanation is known as the Serial endosymbiosis theory (SET), articulated and championed by scientist Lynn Margulis. In 1905 Russian scientist Konstantin Merezhkovsky proposed that new organs or organisms could form through symbiosis (“the living together of different kinds of organisms”). In the 1920s researcher Ivan Wallin suggested that organelles such as chloroplasts and mitochondria originated as symbiotic bacteria. His theory was rejected by his colleagues, leading him to abandon his laboratory investigations.

However, in 1967 the theory was resuscitated by Margulis to explain observations by geneticists of “cytoplasmic genes,” DNA found outside the nucleus. Margulis proposed that cytoplasmic organelles with a bacterial origin were the source of the extranuclear genes. Margulis’s SET begins with the merger of an archaebacterium, lacking a rigid cell wall, with motile spirochetes to form the first eukaryotic cell. The archeabacterium’s flexible membrane pinched inwards to enclose the DNA within a double-membrane nucleus and the spirochetes provided cytoskeletal support, ultimately giving rise to motile structures known as microtubules.

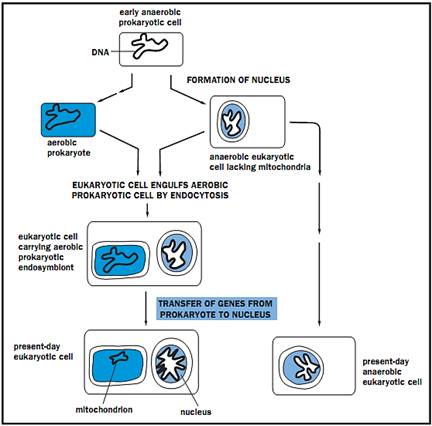

This new cell type then engulfed an aerobic (needing oxygen) bacterium, which was retained within a membrane vesicle inside the host cell. Over many generations, this new cell component evolved into what scientists now call “mitochondrion” and allowed eukaryotes to thrive in an oxygen-rich environment by harnessing the metabolic capabilities of its newest partner. Over time, many of the proto-mitochondrion’s genes were transferred to the host nucleus, making the mitochondrion dependent upon the host cell for its survival. In a similar fashion, some of these aerobic nucleated cells established symbiotic associations with intracellular cyanobacteria, leading to the evolution of photosynthetic eukaryotes.

Suggested evolutionary pathway for the origin of mitochondria

The view that the eukaryotic cell evolved from an intimately associated consortium of bacteria initially met with sharp criticism. Some, including Margulis, argued that the discovery that both mitochondria and plastids contain bacteria-like circular chromosomes, the source of the “cytoplasmic genes,” was evidence for the bacterial origins of these double-membrane- bound organelles. Others argued, however, that these organelles and their genes originated by pinching off from the nucleus.

Eventually researchers accumulated more and more supporting evidence for the main premise of SET: the symbiotic origin of mitochondria and plastids. The size, gene structure and sequences, biochemistry, and fission-style reproduction of these organelles all imply a closer evolutionary relationship to free-living aerobic bacteria and cyanobacteria than to the “host” archaebacteria-derived cell encoded by genes in the nucleus. The origin of microtubules from spirochete symbionts, however, is not as well supported and remains controversial. One of the reasons the theory met with such initial skepticism is that it challenged the prevailing ideas about how evolution occurs: that is, through slow accumulations of changes in vertically transmitted sets of genes, resulting in speciation events in which branches of the tree of life are forever splitting, never joining. SET describes the wholesale fusion of two (three, four, or more) genomes, a process that joined previously diverging branches into one.

References

De Duve, Christian. “The Birth of Complex Cells.” Scientific American 274 (1996): 50-57.

Margulis, Lynn. Symbiotic Planet: A New Look at Evolution. New York: Basic Books, 1998.

|

|

|

|

مخاطر خفية لمكون شائع في مشروبات الطاقة والمكملات الغذائية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"آبل" تشغّل نظامها الجديد للذكاء الاصطناعي على أجهزتها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

تستخدم لأول مرة... مستشفى الإمام زين العابدين (ع) التابع للعتبة الحسينية يعتمد تقنيات حديثة في تثبيت الكسور المعقدة

|

|

|