Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-08-19

Date: 2023-05-01

Date: 2023-04-01

|

This type has the same two roles as LIKING—an Experiencer gets a certain feeling about a Stimulus—but they are mapped differently onto syntactic relations, Stimulus becoming A and Experiencer O, e.g. frighten, terrify, scare, shock, upset, surprise; offend; delight, please, satisfy, entertain, amuse, excite, inspire; impress, concern, trouble, worry, grieve, dismay, depress, sadden; madden, infuriate, annoy, anger, disappoint; confuse, bewilder, deceive, trick, perplex, puzzle; interest, distract, bore; attract; embarrass, disgust; tire, exhaust, bother.

As mentioned earlier, some AFFECT verbs show a metaphorical sense and then have meaning and grammar similar to the ANNOYING type, taking an NP or a complement clause as A argument. For example, The bad news broke my spirit, That he had not been promoted really cut John up, To have to help wash up stretched Mary’s patience, and For John to get the job ahead of me stung me to the quick.

All ANNOYING verbs are transitive. Some do have meanings similar to those of LIKING verbs (e.g. please and delight are almost converses of like and love—if X pleases Y it is likely that Y likes X, and vice versa) but most have meanings rather different from those of the LIKING type.

The syntactic frames we outlined for LIKING apply almost exactly to ANNOYING verbs, with A and O reversed, e.g.

I. Horses/Mary/your uncle/the wet season annoy(s) Fred

IIa. John’s playing baseball annoys Fred

IIb. Playing baseball annoys Fred

IIIa. The proposal annoys Fred

IIIb. The proposal about baseball annoys Fred

IIIc. The proposal about (our) playing baseball instead of cricket on Saturdays annoys Fred

IIId. The proposal that we should switch to baseball annoys Fred

IIIe. The proposal for us to switch to baseball annoys Fred

IIIf. The proposal to switch to baseball annoys Fred

We presented evidence—from adverb placement—that a THAT, or Modal (FOR) TO clause, as the Content part of Stimulus, may be extraposed to the end of the clause, with the Label remaining in its original syntactic slot. This happens very plainly for ANNOYING verbs, where the extraposition is from A slot, i.e.

III’d. The proposal annoys Fred that we should switch to baseball

III’e. The proposal annoys Fred for us to switch to baseball

III’f. The proposal annoys Fred to switch to baseball

(It should be noted that speakers differ over the acceptability of III’d–’f.)

LIKING verbs also occur in IIId’/e’/f’ where the Label is either omitted or replaced by it; the complement clause can again be transposed. These possibilities are once more clearly distinguished for verbs from the ANNOYING type:

IIId’. That we now play baseball annoys Fred

IIIe’. For us to switch to baseball would annoy Fred

IIIf’. To switch to baseball would annoy Fred

III’d’. It annoys Fred that we now play baseball

III’e’. It would annoy Fred for us to switch to baseball

III’f’. It would annoy Fred to switch to baseball

A minor syntactic difference is now revealed. Most LIKING verbs take it before a THAT clause and also have it before a full (FOR) TO complement (but omit it when the for is dropped). ANNOYING verbs retain it in subject slot for all three complement types when they are extraposed, but cannot include it when the complement clause stays in A slot. The inclusion of it when extraposition has taken place is necessary to satisfy the surface structure constraint that there be something in the subject slot for every main clause in English. The omission of it when there is no extraposition is also due to a surface syntactic constraint—no sentence in English may begin with it that, it for or it to.

(It is in keeping with the general syntactic structure of English that an ING complement generally cannot be extraposed; there can be what is called ‘right dislocation’, a quite different syntactic phenomenon, which is marked by contrastive intonation, shown in writing by a comma, e.g. II’a It annoys Fred, John’s playing baseball.)

Not all verbs from this type occur equally freely with all kinds of complement; Modal (FOR) TO constructions may be especially rare for some. This relates to the meanings of the complement constructions and the meanings of the verbs. No hard and fast occurrence restrictions are evident as a basis for establishing subtypes.

Most verbs in this type do not allow an O NP to be omitted (even if it has a very general meaning, e.g. He amuses everyone). There are just two or three that occasionally occur with no Experiencer stated, in marked contexts, e.g. He always offends, She does annoy, He can entertain, can’t he! A small subset of ANNOYING verbs may also be used intransitively, with S = O (i.e. the Experiencer is then in S relation). These include worry, grieve and delight, e.g. The behavior of his daughter worries/grieves John, John worries/grieves a lot (over the behavior of his daughter); Playing golf delights John, John delights in playing golf. (Note that there is semantic difference here: used transitively these verbs imply that it is the Stimulus which engenders the feeling in the Experiencer; used intransitively they imply an inherent propensity, on the part of the Experiencer, to the feeling.)

The passive participle—which is still a verbal form although it behaves in some ways like an adjective—and the past participle—which is a derived adjective—coincide in form (e.g. broken in The window was broken by Mary and in the broken window). With ANNOYING verbs it is not an easy matter to distinguish between a passive construction and a copula-plus-past-participle construction. Consider:

(1a) John’s winning the race surprised me

(2a) The result surprised me

(1b) I was surprised at/by John’s winning the race

(2b) I was surprised at/by the result

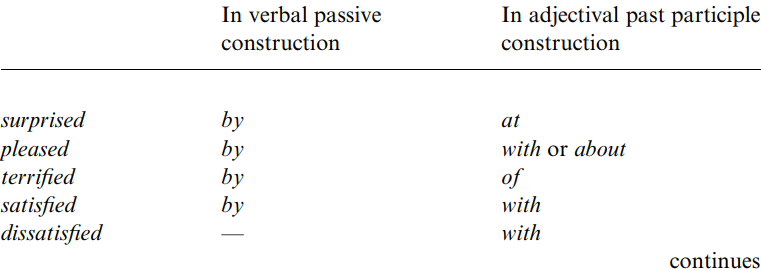

Sentences (1b) and (2b) have the syntactic appearance of passives except that the preposition may be at or by (carrying a slight meaning difference) whereas in a normal passive the underlying A can only be introduced with by. Note that we can have at or by after surprised, about or with or by after pleased, in or by after interested, of or by after terrified, etc. There is in each case a meaning difference, e.g. terrified by a noise (something specific), terrified of strangers (a general phenomenon). By is always one possibility, suggesting that this alternative could constitute a passive construction, with the other alternative (featuring at or about or with or of or in, etc.) marking an adjectival construction.

Adjectives from the ANGRY and HAPPY subtypes of HUMAN PROPENSITY have similar meanings to past participles of some ANNOYING verbs. These can introduce the Stimulus role by a preposition, e.g. angry about, jealous of, sorry about, ashamed of. It appears always to be a preposition other than by, lending support for the position that (1b) and (2b) with surprised by are passives, while (1b) and (2b) with surprised at are not passives but parallel to a construction with copula plus HMAN PROPENSITY adjective.

One syntactic test for distinguishing between verbal and adjectival forms is that only the latter can be modified by very, e.g. we can say This hat is very squashed—where squashed is a derived adjective—but not *This hat was very squashed by Mary or *Jane was very seen by her brother—where squashed and seen are passive verbal forms. Most speakers accept very with surprised at, pleased with, interested in (supporting our contention that these are adjectival constructions) but are less happy when very is used with surprised by, pleased by, interested by (supporting our treatment of these as passive constructions).

There is one apparent counter-example. The prefix un- can be added to some verbs from the AFFECT type with a reversative meaning (e.g. untie, uncover), and to some adjectives from HUMAN PROPENSITY, QUALIFICATION, VALUE, SIMILARITY and PHYSICAL PROPERTY forming an antonym (e.g. unkind, impossible, unlike). The antonymic sense of un- never occurs with a verb. Thus we get verb impress, derived adjective impressed, and negative adjective unimpressed (but not a negative verb *un-impress). However, unimpressed can be followed with by, e.g. I was (very) unimpressed by his excuses. How can it be that by occurs with unimpressed, something that is not a verbal form?

This apparent counter-example can be explained. We have seen that a passive construction takes by, whereas a derived adjective (the past participle) may take one of an extensive set of prepositions; which preposition is chosen depends on the meaning of the past participle and of the preposition. This set of prepositions does include by, and it is this which is used with the adjectival forms impressed and unimpressed. Thus:

We see that dissatisfied, uninterested and unimpressed (which must be adjectival forms) take the same preposition, in the right-hand column, as satisfied, interested and impressed (which can be verbal or adjectival). It is just that impressed and unimpressed take by in the right-hand column, the same preposition that occurs with all verbs in a passive construction, as shown in the left-hand column. Unimpressed is an adjective, which takes by in the same way that uninterested takes in.

Since impressed has by in both columns, a sentence such as John was impressed by the report is ambiguous between passive and past participle interpretations. We also encounter ambiguity when a THAT or Modal (FOR) TO complement clause is involved. Compare:

(3a) That John won the race surprised me/It surprised me that John won the race

(3b) I was surprised that John won the race

Sentence (3a) is a normal active construction with an ANNOYING verb; (3b) could be either the passive of (3a) or a copula-plus-past-participle construction. Since, by a general rule of English, a preposition is automatically dropped before complementiser that (or for or to) we cannot tell, in the case of (3b), whether the underlying preposition is by or at.

Past participles of many ANNOYING verbs may—like adjectives—occur in construction with a verb of the MAKE type, e.g. make confused, make depressed. It is instructive to compare:

(4a) The pistol shot in the airport frightened me

(4b) The stories I’ve heard about pistol shots in airports have made me frightened (of ever visiting an airport)

The transitive verb frighten, in (4a), refers to the Stimulus putting the Experiencer directly in a fright. Make-plus-past-participle-frightened, in (4b), refers to the Stimulus causing the Experiencer, less directly, to get into a fright.

Some verbs of the ANNOYING type are morphologically derived from adjectives, e.g. madden and sadden, from mad and sad, members of the ANGRY subtype of HUMAN PROPENSITY (here we would say make mad/sad, parallel to make frightened in (4b); we would not say make maddened/saddened). Quite a number of verbs from this type also function as nouns, with the same form, e.g. scare, shock, upset, surprise, delight, concern, trouble, worry, puzzle, interest, bore, bother. Some have nouns derived from them, e.g. amusement, offence, satisfaction, confusion; and a few are verbs derived from nouns, e.g. frighten from fright, terrify from terror.

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اتحاد كليات الطب الملكية البريطانية يشيد بالمستوى العلمي لطلبة جامعة العميد وبيئتها التعليمية

|

|

|