Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 3-2-2022

Date: 2023-06-08

Date: 2023-09-26

|

We noted that theoretical considerations lead us to conclude that, if transitive vPs are phases, wh-movement must involve movement through intermediate spec-vP positions in transitive clauses. An important question to ask, therefore, is whether there is any empirical evidence of wh-movement through spec-vP. We shall see that there is.

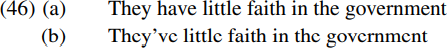

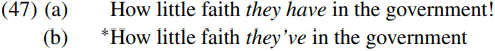

One such piece of evidence comes from observations about have-cliticisation. In varieties of English such as my own, have when used as a main verb marking possession can contract onto an immediately adjacent pronoun ending in a vowel or diphthong, e.g. in sentences such as (46) below:

However, cliticisation is blocked when the object of have undergoes wh-movement, as we see from sentences like those below:

To see why this should be, let’s take a closer look at the derivation of (47).

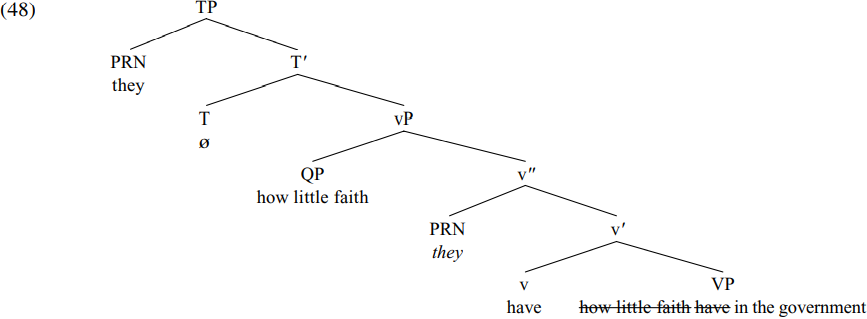

The verb have merges with the prepositional phrase in the government to form the V-bar have in the government. This is then merged with the QP how little faith to form the VP how little faith have in the government. The resulting VP is merged with a null light verb forming a v-bar which is in turn merged with its subject they, and the verb have raises to adjoin to the light verb. Being transitive, the light verb assigns accusative case to how little faith. Since a transitive light verb is a phase head, the light verb will carry [WH, EPP] features which trigger movement of the wh-marked QP how little faith to spec-vP. The resulting vP is merged with a T constituent which agrees with, case-marks and triggers movement to spec-TP of the subject they, so that on the TP cycle we have the structure shown in simplified form in (48) below:

Since a finite T is generally able to attract possessive have to move from V to T, we might expect have to move from v to T at this point. But if have moves to T, it will then be adjacent to the subject they, leading us to expect have to be able to cliticise onto they in the PF component, so wrongly predicting that (47b) is grammatical. How can we prevent have cliticisation in such structures? One answer is to suppose that movement of have from v to T is blocked in structures like (48) by the intervening raised object how little faith in the outer spec-vP position. This would mean that the verb have remains in the head v position of vP rather than moving into T; and if have cannot move into T, it will not be adjacent to (and so cannot cliticise onto) the subject they in spec-TP. As should be obvious, this kind of account is crucially dependent on the assumption that the preposed wh-phrase how little faith moves through spec-vP before moving into spec-CP.

Interestingly, it would seem that an intervening non-object constituent does not block movement of have from v to T, as we see from the fact that have-cliticisation is possible in sentences such as:

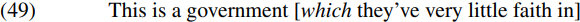

If transitive vPs are phases and trigger wh-movement to spec-vP, at the stage of derivation corresponding to that in (48) above, the bracketed relative clause in (49) will have the structure shown in simplified form in (50) below:

However, since which is not the object of have in (50) but rather is the object of the preposition in, it does not prevent have raising from v to T, and thereafter cliticising onto the subject they in spec-TP. So it would seem that (for reasons which are not clear) have is prevented from raising to T across its own object, but not across other intervening constituents.

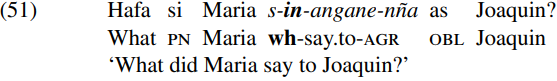

A very different kind of evidence in support of wh-movement through spec-vP in transitive clauses comes from wh-marking of verbs (in languages with a richer verb morphology than English). We saw that a complementizer is wh-marked (in languages like Irish and Chamorro) if it has [EPP, WH] features and attracts a wh-marked goal. Chung (1994, 1998) presents evidence that whmovement out of a transitive verb phrase likewise triggers wh-marking of the verb in Chamorro. We can illustrate this phenomenon of wh-marking of transitive verbs in terms of the following example (from Chung 1998, p. 242):

(PN denotes a person/number marker, AGR an agreement marker, and OBL an oblique case marker.) The crucial aspect of the example in (51) is that the direct object hafa ‘what’ has been moved out of the transitive verb phrase in which it originates, and that this movement triggers wh-marking of the italicized verb, which therefore ends up carrying the wh-infix in. This suggests that a transitive light verb carrying [EPP, WH] features attracts a wh-marked goal and undergoes agreement with the goal, resulting in the verb which is adjoined to the light verb being overtly wh-marked (though see Dukes 2000 for an alternative perspective on the relevant affixes in Chamorro). For further examples of wh-marking of intermediate verbs in long-distance wh-movement structures, see Branigan and MacKenzie (2002) on Innu-aimˆun, and den Dikken (2001) on Kilega.

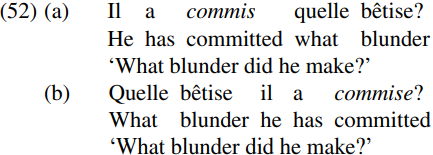

A related piece of evidence comes from participle agreement in French in transitive clauses such as (52b) below (discussed in Kayne 1989, Branigan 1992, Ura 1993, 2001, Boˇskovi´c 1997, Richards 1997 and Sportiche 1998):

The participle commis ‘committed’ is in the default (masculine-singular) form in (52a), and does not agree with the feminine-singular in-situ wh-object quelle betise ˆ ‘what blunder’ (the final -e in these words can be taken to be an orthographic marker of a feminine-singular form). However, the participle commise in (52b) contains the feminine-singular marker -e and agrees with its preposed feminine-singular object quelle betise ˆ ‘what blunder’ and consequently rhymes with betise ˆ . What’s going on here?

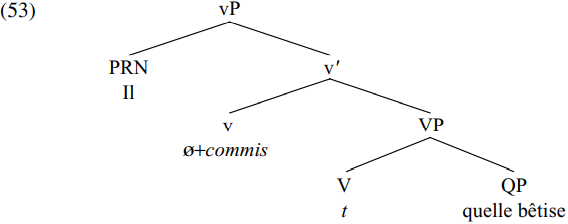

Let’s look first at the derivation of (52a). The QP quelle betise ˆ ‘what blunder’ in (52a) is merged as the complement of the verb commis ‘committed’ forming the VP commis quelle betise ˆ ‘committed what blunder’. The resulting VP is then merged with a null transitive light verb whose external AGENT argument is the pronoun il ‘he’; since the light verb is affixal, it triggers movement of the verb commis ‘committed’ to adjoin to the light verb, so that at the end of the vP phase we have the structure (53) below:

The light verb agrees in person/number  -features with the object quelle betise ˆ ‘what blunder’ and assigns it accusative case. By hypothesis, the light verb has no [EPP] feature in wh-in-situ questions, so there is no movement of the wh-phrase quelle betise ˆ ‘what blunder’ to spec-vP. Subsequently the vP (53) is merged as the complement of the auxiliary a ‘has’ which agrees in person/number

-features with the object quelle betise ˆ ‘what blunder’ and assigns it accusative case. By hypothesis, the light verb has no [EPP] feature in wh-in-situ questions, so there is no movement of the wh-phrase quelle betise ˆ ‘what blunder’ to spec-vP. Subsequently the vP (53) is merged as the complement of the auxiliary a ‘has’ which agrees in person/number  - features with (and triggers movement to spec-TP of) the subject il ‘he’. Merging the resulting TP with a null complementizer which likewise has no [EPP] feature derives the structure associated with (52a) Il a commis quelle betise? ˆ (literally ‘He has committed what blunder?’).

- features with (and triggers movement to spec-TP of) the subject il ‘he’. Merging the resulting TP with a null complementizer which likewise has no [EPP] feature derives the structure associated with (52a) Il a commis quelle betise? ˆ (literally ‘He has committed what blunder?’).

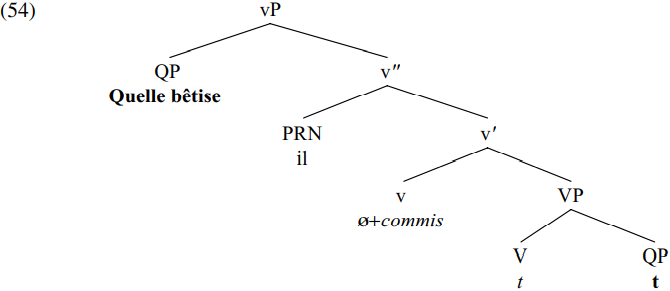

Now consider the derivation of (52b). This is similar in a number of respects to that of (52a), so that (as before) the light verb agrees in person and number with (and assigns accusative case to) its object quelle betise ˆ ‘what blunder’. But in addition, the light verb has [WH, EPP] features, and these attract the wh-marked object quelle betise ˆ ‘what blunder’ to move to become an additional (outer) specifier for the vP, so deriving the structure shown in (54) below:

The resulting vP (54) is then merged as the complement of the auxiliary a ‘has’ which agrees in  -features with (and triggers movement to spec-TP of) the subject il ‘he’. Merging the resulting TP with a null interrogative complementizer which has [EPP, WH]features triggers movement of the wh-phrase to spec-CP, so deriving the structure associated with (52b) Quelle betise il a commise? ˆ (literally ‘What blunder he has committed?’)

-features with (and triggers movement to spec-TP of) the subject il ‘he’. Merging the resulting TP with a null interrogative complementizer which has [EPP, WH]features triggers movement of the wh-phrase to spec-CP, so deriving the structure associated with (52b) Quelle betise il a commise? ˆ (literally ‘What blunder he has committed?’)

In the light of the assumptions made above, consider why the participle surfaces in the agreeing (feminine-singular) form commise ‘committed’ in (52b), but in the non-agreeing (default) form commis in (52a). Bearing in mind our earlier observation that (in languages like Irish) a complementizer only shows overt wh-marking if it has an [EPP] feature as well as a [WH] feature, a plausible suggestion to make is that French participles only overtly inflect for gender/number agreement with their object if they have an [EPP] feature which forces movement of the object through spec-vP. However, any such assumption requires us to suppose that wh-movement proceeds through spec-vP in transitive clauses, and hence lends further support for Chomsky’s claim that transitive vPs are phases. (The discussion here is simplified in a number of respects for expository purposes, e.g. by ignoring the specificity effect discussed by Richards 1997 pp. 158–60, and additional complications discussed by Ura 2001.)

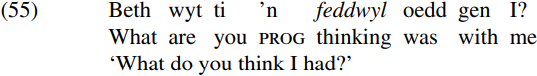

Further evidence in support of successive-cyclic wh-movement through spec-vP in transitive clauses comes from observations about mutation in Welsh made in Tallerman (1993). Tallerman claims that wh-traces trigger so-called soft mutation of the initial consonant of a following word. In this connection, consider the sentence in (55) below (where PROG denotes a progressive aspect marker):

What is particularly interesting here is that the italicized verb has undergone soft mutation, so that in place of the radical form meddwyl ‘thinking’, we find the mutated form feddwyl. Given independent evidence that Tallerman produces in support of claiming that wh-traces induce mutation, an obvious way of accounting for the use of the mutated verb-form feddwyl ‘thinking’ in (55) is to suppose that the wh-pronoun beth ‘what’ moves through spec-vP on its way to the front of the overall sentence, in much the same way as what moves in front of think in (24) above. We can then suppose that a wh-trace on the edge of vP triggers soft mutation on the lexical verb adjoined to the light verb heading the vP. (See Willis 2000 for a slightly different account of Welsh mutation.)

A further argument in support of wh-movement through spec-vP in transitive clauses comes from Spanish multiple-wh questions such as (56) below (discussed by Boˇskovi´c 1997):

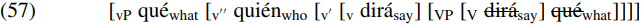

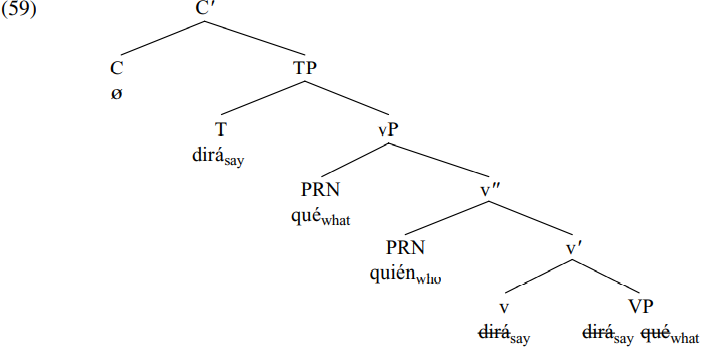

Adapting Boˇskovi´c’s account of this contrast to the framework presented here, let’s suppose that (56) is derived as follows. The verb (which ultimately surfaces in the form) dira´ ‘will.say’ (glossed simply as say in the numbered structures below, in order to save space) is merged with its complement que´ ‘what’ to form the VP dira qu´e´ ‘will.say what’. This in turn is merged with a transitive light verb which assigns accusative case to que´ ‘what’, triggers raising of the verb dira´ ‘will.say’ from V to v, and merges with its AGENT argument quien´ ‘who’. On the assumption that transitive vPs are phases, and that a wh-object which moves to spec-CP moves through spec-vP, the light verb will also have [EPP, WH] features which trigger raising of the closest wh-expression c-commanded by the light verb (namely the wh-object que´ ‘what’) to become a second (outer) specifier for vP, forming the structure shown in skeletal form below (with strikethrough used to indicate constituents which ultimately receive a null spellout after transfer):

The resulting vP in (57) is then merged with an abstract T constituent, to form a TP. Given that Su˜ner (1994) argues that postverbal subjects in Spanish remain in situ within the verb phrase but that verbs move to T in finite clauses, we can assume that the verb dira´ ‘will.say’ moves from v to T, but the subject quien´ ‘who’ remains in situ in spec-vP, so that at the end of the TP cycle we have formed the skeletal structure:

The resulting TP is then merged with a null interrogative complementizer, to form the structure below:

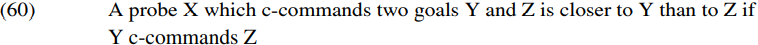

As in main-clause questions in English, C has [TNS, WH, EPP] features. The affixal [TNS] feature of C triggers raising of the verb dira´ ‘will.say’ from T to C. The Attract Closest Principle requires the [EPP, WH]features of C to attract the closest wh-expression to move to spec-CP. Suppose that (following Chomsky 1995, p. 358) we define closeness in terms of c-command, along the lines outlined below:

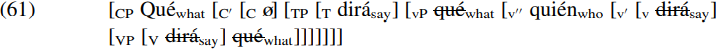

(Note, incidentally, that this is a different definition of closeness, raising obvious questions about precisely how closeness should be defined – but we’ll set this issue aside here.) It will then follow that (by virtue of having moved to the outer specifier position within vP) the wh-object que´ ‘what’ is closer to C than the wh-subject quien´ ‘who’. Accordingly, it is the former which moves to spec-CP, deriving the structure (61) below:

And (61) is the structure of (56) Que´ dira´ quien? ´ ‘What will who say?’ Note that a crucial plank in the argumentation is the assumption that a wh-object in a transitive clause like (56) moves to spec-CP through spec-vP. (However, see Fitzpatrick 2002, pp. 457–8 for discussion of a potential problem.)

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتبة أمّ البنين النسويّة تصدر العدد 212 من مجلّة رياض الزهراء (عليها السلام)

|

|

|