Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 1-2-2022

Date: 2023-12-06

Date: 2023-11-25

|

We have argued that phrases and sentences are formed by a series of binary merger operations, and that the resulting structures can be represented in the form of tree diagrams. Because they mark the way that words are combined together to form phrases of various types, tree diagrams are referred to in the relevant technical literature as phrase-markers (abbreviated to P-markers). They show us how a phrase or sentence is built up out of constituents of various types: hence, a tree diagram provides a visual representation of the constituent structure of the corresponding expression. Each node in the tree (i.e. each point in the tree which carries a category label like  etc.) represents a different constituent of the sentence; hence, there are as many different constituents in any given phrase-marker as there are nodes carrying category labels. Nodes at the very bottom of the tree are called terminal nodes, and other nodes are non-terminal nodes: so, for example, all the D, N, T, V and P nodes in (44) are terminal nodes, and all the DP, PP, VP,

etc.) represents a different constituent of the sentence; hence, there are as many different constituents in any given phrase-marker as there are nodes carrying category labels. Nodes at the very bottom of the tree are called terminal nodes, and other nodes are non-terminal nodes: so, for example, all the D, N, T, V and P nodes in (44) are terminal nodes, and all the DP, PP, VP,  and TP nodes are non-terminal nodes. The topmost node in any tree structure (i.e. TP in the case of (44) above) is said to be its root. Each terminal node in the tree carries a single lexical item (i.e. an item from the lexicon/dictionary, like dog or go etc.): lexical items are sets of phonological, semantic and grammatical features (with category labels like N, V, T, C etc. being used as shorthand abbreviations for the set of grammatical features carried by the relevant items).

and TP nodes are non-terminal nodes. The topmost node in any tree structure (i.e. TP in the case of (44) above) is said to be its root. Each terminal node in the tree carries a single lexical item (i.e. an item from the lexicon/dictionary, like dog or go etc.): lexical items are sets of phonological, semantic and grammatical features (with category labels like N, V, T, C etc. being used as shorthand abbreviations for the set of grammatical features carried by the relevant items).

It is useful to develop some terminology to describe the syntactic relations between constituents, since these relations turn out to be central to syntactic description. Essentially, a P-marker is a graph comprising a set of po

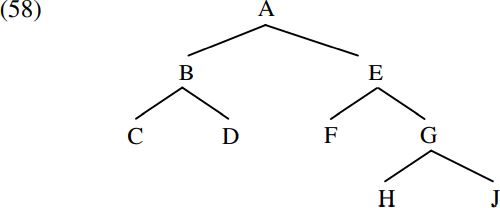

(= labelled nodes), connected by branches (= solid lines) representing containment relations (i.e. telling us which constituents contain or are contained within which other constituents). We can illustrate what this means in terms of the following abstract tree structure (where A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H and J are different nodes in the tree, representing different constituents):

In (58), G immediately contains H and J (and conversely H and J are the two constituents immediately contained within G, and hence are the two immediate constituents of G): this is shown by the fact that H and J are the two nodes immediately beneath G which are connected to G by a branch (solid line). Likewise, E immediately contains F and G; B immediately contains C and D; and A immediately contains B and E. We can also say that E contains F, G, H and J; and that A contains B, C, D, E, F, G, H and J (and likewise that G contains H and J; and B contains C and D). Using equivalent kinship terminology, we can say that A is the mother of B and E (and conversely B and E are the two daughters of A); B is the mother of C and D; E is the mother of F and G; and G is the mother of H and J. Likewise, B and E are sisters (by virtue of both being daughters of A) – as are C and D; F and G; and H and J.

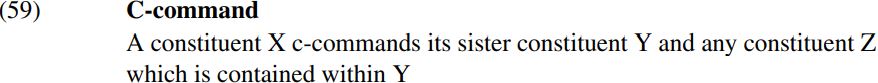

A particularly important syntactic relation is c-command (a conventional abbreviation of constituent-command), which provides us with a useful way of determining the relative position of two different constituents within the same tree (in particular, whether one is lower in the tree than the other or not). We can define this relation informally as follows (where X, Y and Z are three different nodes):

Amore concrete way of visualizing this is to think of a tree diagram as representing a network of train stations, with each of the labelled nodes representing the name of a different station in the network, and the branches representing the rail tracks linking the stations. We can then say that one node X c-commands another node Y if you can get from X to Y on the network by taking a northbound train, getting off at the first station, changing trains there and then travelling one or more stops south on a different line.

Amore concrete way of visualizing this is to think of a tree diagram as representing a network of train stations, with each of the labelled nodes representing the name of a different station in the network, and the branches representing the rail tracks linking the stations. We can then say that one node X c-commands another node Y if you can get from X to Y on the network by taking a northbound train, getting off at the first station, changing trains there and then travelling one or more stops south on a different line.

In the light of the definition of c-command given above, let’s consider which constituents each of the nodes in (58) c-commands. A doesn’t c-command any of the other nodes, since A has no sister. B c-commands E, F, G, H and J because B’s sister is E, and E contains F, G, H and J. C c-commands only D, because C’s sister is D, and D does not contain any other constituent; likewise, D c-commands only C. E c-commands B, C and D because B is the sister of E and B contains C and D. F c-commands G, H and J, because G is the sister of F and G contains H and J. G c-commands only F, because G’s sister is F, and F does not contain any other constituents. H and J likewise c-command only each other because they are sisters which have no daughters of their own.

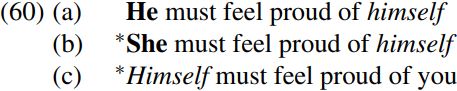

We can illustrate the importance of the c-command relation in syntactic description by looking at the distribution of a class of expressions which are known as anaphors. These include reflexives (i.e. self/selves forms like myself/yourself/themselves etc.) and reciprocals like each other and one another. Such anaphors have the property that they cannot be used to refer directly to an entity in the outside world, but rather must be bound by (i.e. take their reference from) an antecedent elsewhere in the same phrase or sentence. Where an anaphor has no (suitable) antecedent to bind it, the resulting structure is ungrammatical – as we see from contrasts such as those in (60) below:

In (60a), the third-person-masculine-singular anaphor himself is bound by a suitable third-person-masculine-singular antecedent (he), with the result that (60a) is grammatical. But in (60b), himself has no suitable antecedent (the feminine pronoun she is not a suitable antecedent for the masculine anaphor himself), and so is unbound (with the result that (60b) is ill-formed). In (60c), there is no antecedent of any kind for the anaphor himself, with the result that the anaphor is again unbound and the sentence ill-formed.

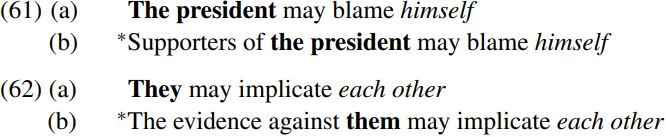

There are structural restrictions on the binding of anaphors by their antecedents, as we see from:

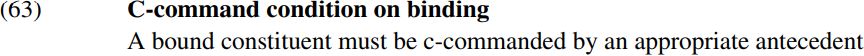

As a third-person-masculine-singular anaphor, himself must be bound by a third-person-masculine-singular antecedent like the president; similarly, as a plural anaphor, each other must be bound by a plural antecedent like they/them. However, it would seem from the contrasts above that the antecedent must occupy the right kind of position within the structure in order to bind the anaphor or else the resulting sentence will be ungrammatical. The question of what is the right position for the antecedent can be defined in terms of the following structural condition:

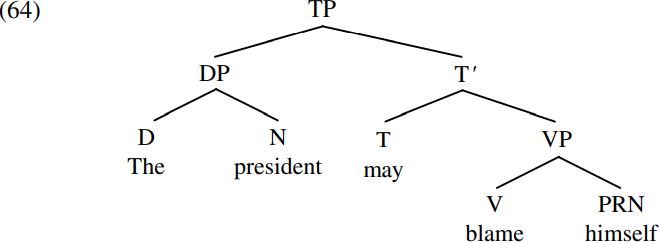

The relevant bound constituent is the reflexive anaphor himself in (61), and its antecedent is the president; the bound constituent in (62) is the reciprocal anaphor each other, and its antecedent is they/them. Sentence (61a) has the structure (64) below:

The relevant bound constituent is the reflexive anaphor himself in (61), and its antecedent is the president; the bound constituent in (62) is the reciprocal anaphor each other, and its antecedent is they/them. Sentence (61a) has the structure (64) below:

The reflexive pronoun himself can be bound by the DP the president in (64) because the sister of the DP node is the T-bar node, and the pronoun himself is contained within the relevant T-bar node (by virtue of being one of the grand children of T-bar): consequently, the DP the president c-commands the anaphor himself and the binding condition (63) is satisfied. We therefore correctly specify that (61a) The president may blame himself is grammatical, with the president interpreted as the antecedent of himself.

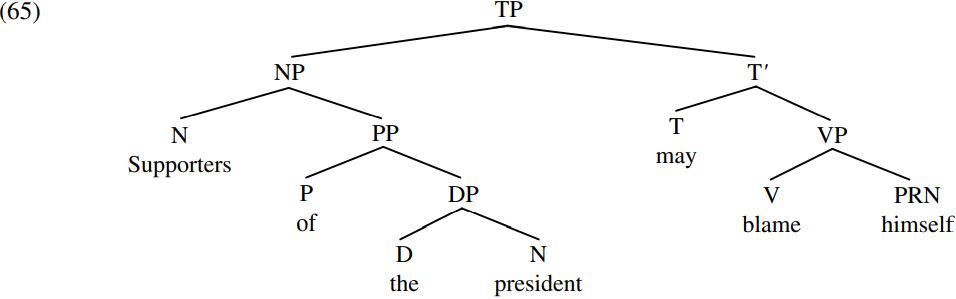

But now consider why a structure like (65) below is ungrammatical (cf. (61b) above):

The answer is that the DP node containing the president doesn’t c-command the PRN node containing himself, because the sister of the DP node is the P node of, and himself is not contained within (i.e. not a daughter, granddaughter, or great-granddaughter etc. of) the preposition of. Since there is no other appropriate antecedent for himself within the sentence (e.g. although the NP supporters of the president c-commands himself, it is not a suitable antecedent because it is a plural expression, and himself requires a singular antecedent), the anaphor himself remains unbound – in violation of the binding requirement on anaphors.

The answer is that the DP node containing the president doesn’t c-command the PRN node containing himself, because the sister of the DP node is the P node of, and himself is not contained within (i.e. not a daughter, granddaughter, or great-granddaughter etc. of) the preposition of. Since there is no other appropriate antecedent for himself within the sentence (e.g. although the NP supporters of the president c-commands himself, it is not a suitable antecedent because it is a plural expression, and himself requires a singular antecedent), the anaphor himself remains unbound – in violation of the binding requirement on anaphors.

This is the reason why (61b) ∗Supporters of the president may blame himself is ungrammatical.

Our brief discussion of anaphor binding here highlights the fact that the relation c-command has a central role to play in syntax. It also provides further evidence for positing that sentences have a hierarchical constituent structure, in that the relevant restriction on the binding of anaphors in (63) is characterized in structural terms. There’s much more to be said about binding, though we shan’t pursue the relevant issues here: for technical discussion, see Reuland (2001a) and Reuland and Everaert (2001).

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اتحاد كليات الطب الملكية البريطانية يشيد بالمستوى العلمي لطلبة جامعة العميد وبيئتها التعليمية

|

|

|