Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 21-4-2022

Date: 19-4-2022

Date: 17-5-2022

|

Reflection: What are you inferring?

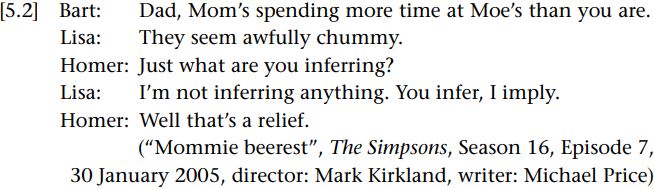

Consider the following conversation from an episode of The Simpsons.

In this example, Bart and Lisa can be understood to be implying that Marge (Homer’s wife) might be having an affair with Moe. This latter proposition counts as an implicature, and it is drawn through a process of inference. Homer, being Homer, next commits the classic mistake of conflating implicature with inference, to which Lisa responds with the well-worn dictum that speakers imply, while hearers infer. Disputes about the distinction between implicature and inference, however, are not restricted to popular discourse. Horn (2004) and Bach (2006), for instance, contend that treating implicature and inference as synonymous constitutes a conceptual and analytical error.

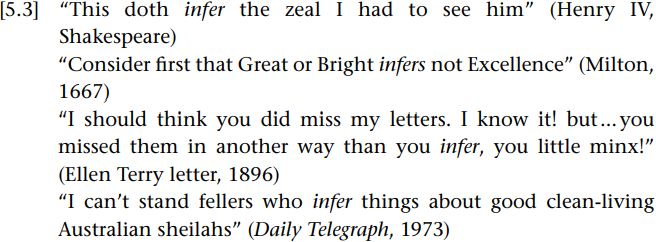

However, there is reason to suspect that Homer may not be entirely wrong in inadvertently mixing up what is implied with what is inferred. First, infer has been used for almost five centuries in the sense of “imply” or “convey” (Horn 2012). Consider the following examples taken from the Oxford English Dictionary Online (2013):

In all of the examples above, infer is used in the sense of “to involve as a consequence” or “to imply”. Second, his claim that Lisa (and Bart) are inferring something here is actually quite correct. They have both inferred from their mother’s recent behavior (e.g. spending a lot of time with Moe, getting on very well with Moe, and so on), along with real-world knowledge about how affairs involving married partners normally arise, that she might be having an affair with Moe. Moreover, they have also presumably inferred that, if they raise this behavior with their father, Homer might come to the same conclusion about the possible implications of Marge’s behavior. Everyone makes inferences, not just hearers. The distinction between imply (cf. implicature) and infer (cf. inference) therefore does not in itself help us distinguish between the speaker’s and hearer’s perspectives on speaker meaning.

Kecskes (2010) argues, however, that a hearer-centred account of pragmatic meaning neglects the speaker’s own perspective, which is perhaps somewhat ironic considering the Gricean roots from which such accounts have sprung. Following Saul’s (2002a) distinction between utterer and audience implicature, one solution to this might be that we must necessarily talk about utterer and recipient representations of speaker meaning. An utterer representation of speaker meaning is what the speaker understands he or she has meant through his or her own utterance. A recipient representation of speaker meaning is what the hearer(s) or other kinds of participants understand the speaker to have meant through his or her utterance. In this way, we can properly recognize, rather than confound, distinct perspectives on speaker meaning.

|

|

|

|

4 أسباب تجعلك تضيف الزنجبيل إلى طعامك.. تعرف عليها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أكبر محطة للطاقة الكهرومائية في بريطانيا تستعد للانطلاق

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تبحث مع العتبة الحسينية المقدسة التنسيق المشترك لإقامة حفل تخرج طلبة الجامعات

|

|

|