Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-01-10

Date: 2024-01-16

Date: 2023-12-09

|

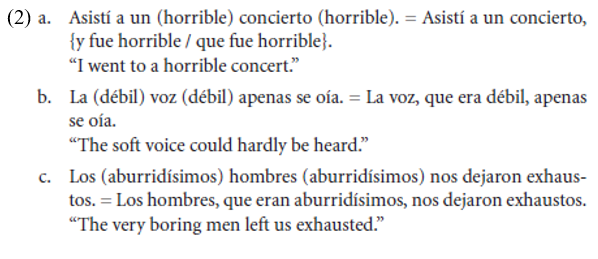

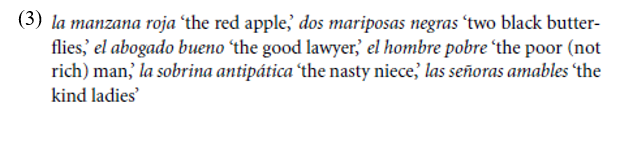

Expressing an extreme property (d)

In (16) we have the logical type of what I call “extreme degree adjectives: certain of Dixon’s human disposition adjectives (horrible ‘horrible,’ necio ‘stupid,’ espantoso ‘awful’) and qualitative superlative adjectives (maravilloso ‘wonderful,’ hermosísimo ‘very beautiful,’ magnífico ‘magnificent’) correspond to this type.1 Considering their function we may call them “appositive” because they serve to express a distinctive or central property of N, as if it were added as a supplement to its denotation.

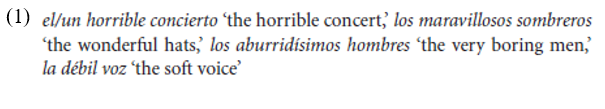

My assertion is that these adjectives are predicative nonrestrictive modifiers, different in this sense from the three preceding types. This is so because in all syntactic contexts in which they occur they do not refer to a subset of the class of objects denoted by N. Moreover, they can be paraphrased as parenthetical or as nonrestrictive relatives. The examples in (1) can be paraphrased as in (2):

Superlative nonrestrictive adjectives like maravillosos in sus/los maravillosos sombreros are usually prenominal in definite expressions; #Sus sombreros maravillosos is less frequent. The reason is that, by default, superlative evaluative adjectives do not serve to delimit a subset of objects; they cannot classify objects in the world since they express not objective properties but rather subjective evaluations. Note that the DP los sombreros maravillosos (where the superlative adjective is postnominal) is acceptable especially when it refers to a set of hats that has not previously been mentioned. In my view, these adjectives fall under the subsidiary generalization I established in the first section: there are semantic and pragmatic reasons which sometimes cause the shifting from the expected R to an NR interpretation when these adjectives are found in postnominal position. I will come back to these, explaining this in terms of focalization as external predicates to the right of NP.

Summarizing, the adjectives in the first three subgroups, from (a) to (c), can be argued to form a single group from a semantic and syntactic point of view. This unification is supported by the assumption that they scope over subparts of the meaning of N, a question to which I will return briefly later on. In contrast to the three subgroups just mentioned, postnominal adjectives (as in 3) normally modify “the individuals determined by all the properties of N” (Bouchard 1998: 143).

Briefly summarizing what we have seen up to this point: the distinction R– NR in interpretation correlates with syntactic position in two senses. First, a reduced set of adjectives are assigned either a restrictive or a nonrestrictive interpretation depending on their position (pobre, completo, simple, antiguo, etc.): I refer to the contrast between el pobre hombre, where the prenominal adjective means “pitiable” vs. el hombre pobre, where pobre is “not rich.” Second, most adjectives are interpreted one way or another depending on their position.

1 Knittel (2005: 193) names these “subjective comment” adjectives. She rightly asserts that these adjectives can be both prenominal and postnominal, and they can be modified by subjective adverbs like verdaderamente ‘truly’ or realmente ‘really.’

|

|

|

|

للعاملين في الليل.. حيلة صحية تجنبكم خطر هذا النوع من العمل

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"ناسا" تحتفي برائد الفضاء السوفياتي يوري غاغارين

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

بمناسبة مرور 40 يومًا على رحيله الهيأة العليا لإحياء التراث تعقد ندوة ثقافية لاستذكار العلامة المحقق السيد محمد رضا الجلالي

|

|

|