Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-06-05

Date: 25-3-2022

Date: 2024-06-22

|

Noun stems fall in two groups in terms of phonological processes: those which begin with a consonant, and those beginning with a vowel. Examples of stems which begin with a consonant are -tesi (cf. mu-tesi, va-tesi) and -lagusi (cf. mu-lagusi, va-lagusi); examples of stems which begin with vowels are -iimbi (cf. mw-iimbi, v-iimbi) and -eendi (mw-eendi, v-eendi). The best phonological information about the nature of the prefix is available from its form before a consonant, so our working hypothesis is that the underlying form of the noun prefix is that found before a consonant it preserves more information.

As we try to understand the phonological changes found with vowel initial stems, it is helpful to look for a general unity behind these changes. One important generalization about the language, judging from the data, is that there are no vowel sequences (what may seem to be sequences such as ii, ee are not sequences, but are the orthographic representation of single long-vowel segments). Given the assumption that the prefixes for classes 1 and 2 are respectively /mu/ and /va/, the expected underlying forms of the words for ‘singer’ and ‘singers’ would be /muiimbi/ and /vaiimbi/. These differ from the surface forms [mw-iimbi] and [v-iimbi]: in the case of /mu-iimbi/, underlying /u/ has become [w], and in the case of underlying /va-iimbi/, underlying [a] has been deleted. In both cases, the end result is that an underlying cluster of vowels has been eliminated.

Glide formation versus vowel deletion. Now we should ask, why is a vowel deleted in one case but turned into a glide in another case? The answer lies in the nature of the prefix vowel. The vowel /u/ becomes the glide [w], and the only difference between u and w is that the former is syllabic (a vowel) where the latter is nonsyllabic. The low vowel /a/, on the other hand, does not have a corresponding glide in this language (or in any language). In other words, a rule of glide formation simply could not apply to /a/ and result in a segment of the language.

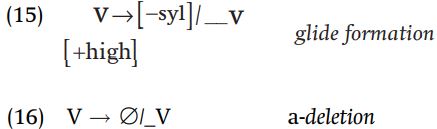

To make progress in solving the problem, we need to advance hypotheses and test them against the data. We therefore assume the following rules of glide formation and vowel deletion.

By ordering (16) after (15), we can make (16) very general, since (15) will have already eliminated other vowel sequences. At this point, we can simply go through the data from top to bottom, seeing whether we are able to account for the examples with no further rules – or, we may find that other rules become necessary.

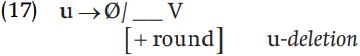

For nouns in class 1, the examples mw-iimbi, mw-eendi, and mw-aasi are straightforward, deriving from /mu-iimbi/, /mu-eendi/, and /mu-aasi/. The forms m-oogofi, m-oofusi, and m-uuci presumably derive from /mu-oogofi/ and /mu-oofusi/ and /mu-uuci/. The vowel /u/ has been deleted, which seems to run counter to our hypothesis that high vowels become glides before vowels. It is possible that there is another rule that deletes /u/ before a round vowel.

We could also consider letting the glide formation rule apply and then explain the difference /mu-aasi/ ! mw-aasi vs. /mu-oofusi/ ! m-oofusi by subjecting derived mw-oofusi to a rule deleting w before a round vowel.

Thus we must keep in mind two hypotheses regarding /u+o/ and /u+u/ sequences.

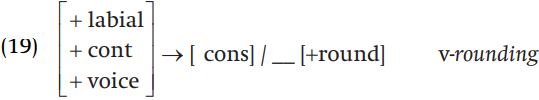

v-rounding. Now consider class 2. In stems beginning with a vowel, we easily explain v-iimbi, v-eendi, and v-aasi from va-iimbi, va-eendi, and va-aasi, where a-deletion applies. Something else seems to be happening in w-oogofi, w-oofusi, and w-uuci from va-oogofi, va-oofusi, and va-uuts i. Application of a-deletion would yield v-oogofi, v-oofusi, and v-uuts i, which differ from the surface forms only in the replacement of v by w. Since this process takes place before a round vowel, we conjecture that there may be an assimilation rule such as the following.

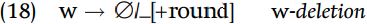

If there is such a rule in the language, it would eliminate any sequences vu, vo: and the data contain no such sequences. There is still a problem to address, that w-deletion (18) should apply to woogofi but it does not – the surface form is not *[oogofi]. Two explanations are available. One is that v-rounding is ordered after w-deletion, so at the stage where w-deletion would apply, this word has the shape voogofi and not woogofi (so w-deletion cannot apply). The other is that (18) needs to be revised, so that it only deletes a postconsonantal w before a round vowel.

Our decision-making criteria are not stringent enough that we can definitively choose between these solutions, so we will leave this question open for the time being.

Moving to other classes, the nouns in class 3 present no problems. Glide formation applies to this prefix, so /mu-iina/ ! [mw-iina], and before a round vowel derived w deletes, so /mu-ooto/ ! mw-ooto which then becomes [m-ooto].

Front vowels and glides. The nouns in class 4 generally conform to the predictions of our analysis. Note in particular that underlying /mi-uuɲu/ and /mi-ooto/ undergo glide formation before a round vowel. Such examples show that it was correct to state the glide formation rule in a more general way, so that all high vowels (and not just /u/) become glides before any vowel (not just nonround vowels).

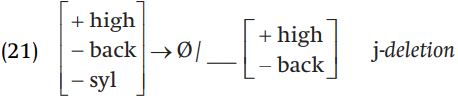

We cannot yet fully explain what happens with noun stems beginning with the vowel i, as in m-iina, m-iigiigi. Given /mi-iina/, /mi-iigiigi/, we predict surface *mj-iina, *mj-iigiigi. This is reminiscent of the problem of /mu-oogofi/ and /mu-uuci/ and we might want to generalize the rule deleting a glide, to include deleting a front glide before a front vowel (analogous to deleting a round glide before a round vowel). What prevents us from doing this is that while w deletes before both u and o, y only deletes before i and not e, as we can see from mj-eenda. It might be more elegant or symmetrical for round glides to delete before round vowels of any height and front glides to delete before front vowels of any height, but the facts say otherwise: a front glide only deletes before a front high vowel.

Checking other classes: discovering a palatalization rule. The class 6 prefix ma- presents no surprises at all: it appears as ma- before a consonant, and its vowel deletes before another vowel, as in m-iino from ma-iino. The class 7 prefix, on the other hand, is more complex. Before a consonant it appears as ki-, and it also appears as k(i)- before i. Before other vowels, it appears as tʃ , as in tʃ -uula, tʃ -aanga, tʃ -ooto, and tʃ -eenda. Again, we continue the procedure of comparing the underlying and predicted surface forms (predicted by mechanically applying the rules which we have already postulated to the underlying forms we have committed ourselves to), to see exactly what governs this discrepancy. From underlying ki-uula, kiaanga, ki-ooto, and ki-eenda we would expect kj-uula, kj-aanga, kj-ooto, and kjeenda, given glide formation. The discrepancy lies in the fact that the predicted sequence kj has been fused into tʃ , a process of palatalization found in many languages. Since kj is nowhere found in the data, we can confidently posit the following rule.

Since /ki/ surfaces as [tʃ ] when attached to a vowel-initial noun stem, the question arises as to what has happened in k-iiho, k-iina, and k-iigiigi. The glide formation rule should apply to /ki-iiho/, /ki-iina/, and /ki-iigiigi/

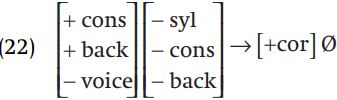

giving kj-iiho, kj-iina, and kj-iigiigi, which we would expect to undergo (22). But there is a rule deleting j before i. If j is deleted by that rule, it could not condition the change of k to tʃ , so all that is required is the ordering statement that j-deletion precedes palatalization (22). Thus /ki-iina/ becomes kj-iina by glide formation, and before the palatalization rule can apply, the j-deletion rule (21) deletes the glide that is crucial for (22).

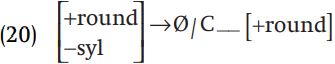

Deciding on the form of w-deletion; degemination. At this point, we can quickly check the examples in classes 8, 11, 12, and 13 and verify that our analysis explains all of these forms as well. The final set of examples are those in class 14, which has the prefix /wu/. This prefix raises a question in terms of our analysis: why do we have the sequence [wu], which is eliminated by a rule elsewhere? One explanation is the statement of the rule itself: if (20) is the correct rule, then this w could not delete because it is not preceded by a consonant. The other possibility is that [wu] actually comes from /vu/ by applying v-rounding (19), which we assumed applies after w-deletion. While both explanations work, the analysis where [wu] is underlying /vu/ has the disadvantage of being rather abstract, in positing an underlying segment in the prefix which never appears as such. This issue was presaged and will be discussed in more detail: for the moment we will simply say that given a choice between a concrete analysis where the underlying form of a morpheme is composed only of segments which actually appear as such in some surface manifestation of the morpheme, and an abstract form with a segment that never appears on the surface, the concrete analysis is preferable to the abstract one, all other things being comparable. On that basis, we decide that the underlying form of the class 14 prefix is /wu/, which means that the proper explanation for failure of w-deletion lies in the statement of w-deletion itself, as (20).

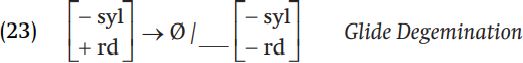

Still analyzing this class of nouns, we now focus on examples where the prefix precedes a vowel-initial stem, e.g. w-eelu, w-uumi, w-oogofu, w-iijooga, and w-aangufu from underlying /wu-eelu/, /wu-uumi/, /wu-oogofu/, /wuiijooga/, and /wu-aangufu/. Applying glide formation would give the surface forms *ww-eelu, *ww-uumi, *ww-oogofu, *ww-iijooga, and *ww-aangufu, which differ from the surface form in a simple way, that they have two w’s where the actual form has only a single w, which allows us to posit the following degemination rule.

|

|

|

|

دور في الحماية من السرطان.. يجب تناول لبن الزبادي يوميا

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العلماء الروس يطورون مسيرة لمراقبة حرائق الغابات

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ضمن أسبوع الإرشاد النفسي.. جامعة العميد تُقيم أنشطةً ثقافية وتطويرية لطلبتها

|

|

|