Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-03-16

Date: 2024-05-29

Date: 9-4-2022

|

The basic tool for converting the continuous stream of speech sound into discrete units is the phonetic transcription. The idea behind a transcription is that the variability and continuity of speech can be reduced to sequences of abstract symbols whose interpretation is predefined, a symbol standing for all of the concrete variants of the sound. Phonology then is the study of higher-level patterns of language sound, conceived in terms of discrete mental symbols, whereas phonetics is the study of how those mental symbols are manifested as continuous muscular contractions and acoustic waveforms, or how such waveforms are perceived as the discrete symbols that the grammar acts on.

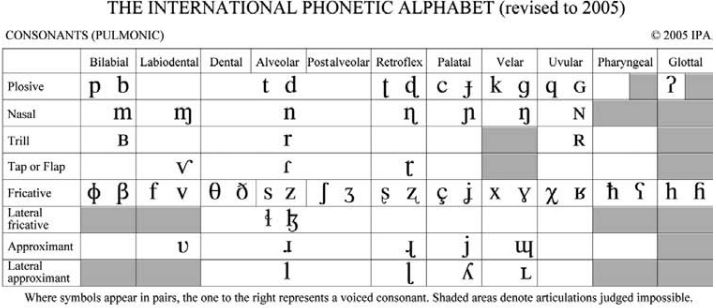

The idea of reducing an information-rich structure such as an acoustic waveform to a small repertoire of discrete symbols is based on a very important assumption, one which has proven to have immeasurable utility in phonological research, namely that there are systematic limits on possible speech sounds in human language. At a practical level, this assumption is embodied in systems of symbols and associated phonetic properties such as the International Phonetic Alphabet of figure 6. Ashby and Maidment (2005) give an extensive introduction to phonetic properties and corresponding IPA symbols, which you should consult for more information on phonetic characteristics of language sound.

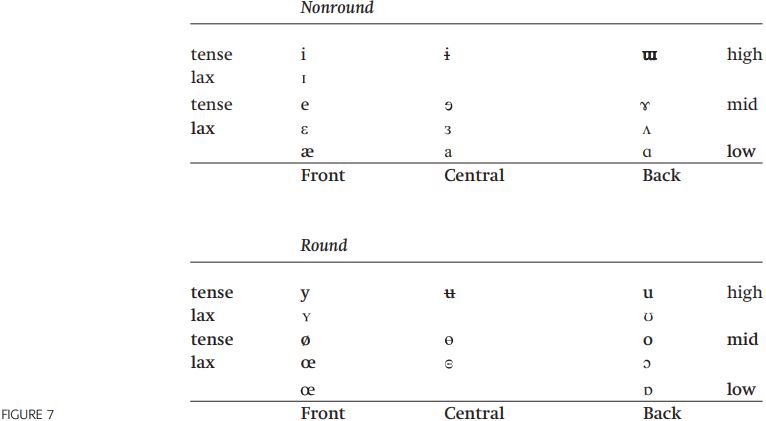

The IPA chart is arranged to suit the needs of phonetic analysis. Standard phonological terminology and classification differ somewhat from this usage. Phonetic terminology describes [p] as a “plosive,” where that sound is phonologically termed a “stop”; the vowel [i] is called a “close” vowel in phonetics, but a “high” vowel in phonology. Figure 7 gives the important IPA vowel letters with their phonological descriptions, which are used to stand for the mental symbols of phonological analysis.

The three most important properties for defining vowels are height, backness, and roundness. The height of a vowel refers to the fact that the tongue is higher when producing [i] than it is when producing [e] (which is higher than when producing [æ]), and the same holds for the relation between [u], [o], and [a].

Three primary heights are generally recognized, namely high, mid, and low, augmented with the secondary distinction tense/lax for nonlow vowels which distinguishes vowel pairs such as [i] (seed) vs. [ɪ] (Sid), [e] (late) vs. [ε] (let), or [u] (food) vs. [ʊ] (foot), where [i, ε, ʊ] are tense and [ɪ, ε, ʊ] are lax. Tense vowels are higher and articulated further from the center of the vocal tract compared to their lax counterparts. It is not clear whether the tense/lax distinction extends to low vowels.

Independent of height, vowels can differ in relative frontness of the tongue. The vowel [i] is produced with a front tongue position, whereas [u] is produced with a back tongue position. In addition, [u] is produced with rounding of the lips: it is common but by no means universal for back vowels to also be produced with lip rounding. Three phonetic degrees of horizontal tongue positioning are generally recognized: front, central, and back. Finally, any vowel can be pronounced with protrusion (rounding) of the lips, and thus [o], [u] are rounded vowels whereas [i], [æ] are unrounded vowels.

With these independently controllable phonetic parameters – five degrees of height, three degrees of fronting, and rounding versus non-rounding – we have the potential for up to thirty vowels, which is many more vowels than are found in English. Many of these vowels are lacking in English, but can be found in other languages. This yields a fairly symmetrical system of symbols and articulatory classifications, but there are gaps such as the lack of tense/lax distinctions among central high vowels.

The major consonants and their classificatory analysis are given in figure 8.

Where the IPA term for consonants like [p b] is “plosive,” these are referred to phonologically as “stops.” Lateral and rhotic consonants are termed “liquids,” and non-lateral “approximants” are referred to as “glides.” Terminology referring to the symbols for implosives, ejectives, diacritics, and suprasegmentals is generally the same in phonological and phonetic usage.

Other classificatory terminology is used in phonological analysis to refer to the fact that certain sets of sounds act together for grammatical purposes. Plain stops and affricates are grouped together, by considering affricates to be a kind of stop (one with a special fricative-type release). Fricatives and stops commonly act as a group, and are termed obstruents, while glides, liquids, nasals, and vowels likewise act together, being termed sonorants.

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جمعية العميد تناقش التحضيرات النهائية لمؤتمر العميد الدولي السابع

|

|

|