النبات

النبات

الحيوان

الحيوان

الأحياء المجهرية

الأحياء المجهرية

علم الأمراض

علم الأمراض

التقانة الإحيائية

التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

علم الأجنة

علم الأجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

الأحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

الغدد

المضادات الحيوية

المضادات الحيوية| Organelle Genomes Are Circular DNAs That Encode Organelle Proteins |

|

|

|

Read More

Date: 22-3-2021

Date: 21-4-2016

Date: 30-12-2015

|

Organelle Genomes Are Circular DNAs That Encode Organelle Proteins

KEY CONCEPTS

-Organelle genomes are usually (but not always) circular molecules of DNA.

-Organelle genomes encode some, but not all, of the proteins used in the organelle.

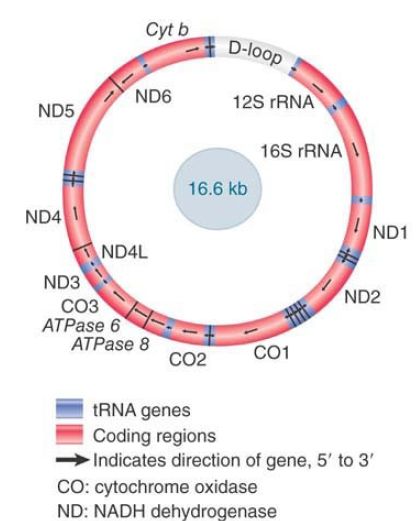

-Animal cell mitochondrial DNA is extremely compact and typically encodes 13 proteins, 2 rRNAs, and 22 tRNAs.

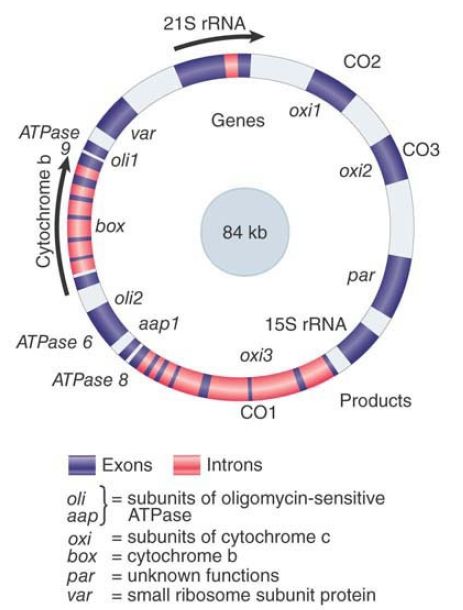

-Yeast mitochondrial DNA is five times longer than animal cell mtDNA because of the presence of long introns.

Most organelle genomes take the form of a single circular molecule of DNA of unique sequence (denoted mtDNA in the mitochondrion and ctDNA or cpDNA in the chloroplast). There are a few exceptions in unicellular eukaryotes for which mitochondrial DNA is a linear molecule.

Usually there are several copies of the genome in the individual organelle. There are multiple organelles per cell; therefore, there are many organelle genomes per cell, so the organelle genome can be considered a repetitive sequence.

Chloroplast genomes are relatively large, usually about 140 kb in higher plants and less than 200 kb in unicellular eukaryotes. This is comparable to the size of a large bacteriophage genome, such as that of T4 at about 165 kb. There are multiple copies of the genome per organelle, typically 20 to 40 in a higher plant, and multiple copies of the organelle per cell, typically 20 to 40.

Mitochondrial genomes vary in total size by more than an order of magnitude. Animal cells have small mitochondrial genomes (approximately 16.6 kb in mammals). There are several hundred mitochondria per cell and each mitochondrion has multiple copies of the DNA. The total amount of mitochondrial DNA relative to nuclear DNA is small; it is estimated to be less than 1%.

In yeast, the mitochondrial genome is much larger. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the exact size varies among different strains but averages about 80 kb. There are about 22 mitochondria per cell, which corresponds to about 4 genomes per organelle. In dividing cells, the proportion of mitochondrial DNA can be as high as 18%. See TABLE .1 and FIGURE 1. for information about the content of the mitochondrial genome and a map of the human mitochondrial genome.

FIGURE 1. Human mitochondrial DNA has 22 tRNA genes, 2 rRNA genes, and 13 protein-coding regions. Fourteen of the 15 proteincoding and rRNA-coding regions are transcribed in the same direction. Fourteen of the tRNA genes are expressed in the clockwise direction and 8 are read counterclockwise.

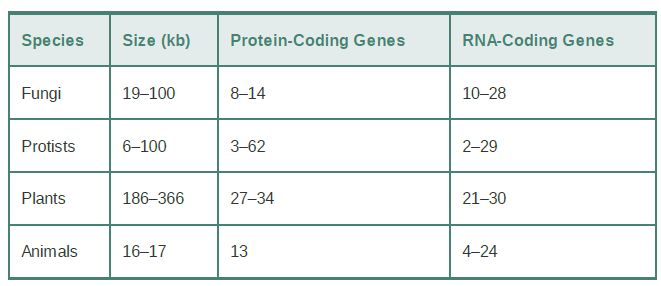

TABLE .1 Mitochondrial genomes have genes encoding (mostly complex I–IV) proteins, rRNAs, and tRNAs.

Plants show an extremely wide range of variation in mitochondrial DNA size, with a minimum size of about 100 kb. The size of the genome makes it difficult to isolate, but restriction mapping in several plants suggests that the mitochondrial genome is usually a single sequence that is organized as a circle. Within this circle there are multiple copies of short homologous sequences. Recombination between these elements generates smaller, subgenomic circular

molecules that coexist with the complete “master” genome—a good example of the apparent complexity of plant mitochondrial DNAs.

With mitochondrial genomes sequenced from many organisms, we can now see some general patterns in the representation of functions in mitochondrial DNA. Table .1 summarizes the distribution of genes in mitochondrial genomes. The total number of protein-coding genes is rather small and does not correlate with the size of the genome. The 16.6-kb mammalian mitochondrial genomes encode 13 proteins, whereas the 60- to 80-kb yeast mitochondrial genomes encode as few as 8 proteins. The much larger plant mitochondrial genomes encode more proteins. Introns are found in most mitochondrial genes, although not in the very small mammalian genomes.

The two major rRNAs are always encoded by the mitochondrial genome. The number of tRNAs encoded by the mitochondrial genome varies from none to the full complement (25 to 26 in mitochondria). This accounts for the variation in Table 1. The major part of the protein-coding activity is devoted to the components of the multisubunit assemblies of respiration complexes I–IV. Many ribosomal proteins are encoded in protist and plant mitochondrial genomes, but there are few or none in fungiand animal gen omes. There are genes encoding proteins involved in cytoplasm-to-mitochondrion import in many protist mitochondrial genomes.

Animal mitochondrial DNA is extremely compact. There are extensive differences in the detailed gene organization found in different animal taxonomic groups, but the general principle of a small genome encoding a restricted number of functions is maintained. In mammalian mitochondria, the genome is particularly compact. There are no introns, some genes actually overlap, and almost every base pair can be assigned to a gene. With the exception of the D-loop, a region involved with the initiation of DNA replication, no more than 87 of the 16,569 bp of the human mitochondrial genome lie in intergenic regions.

The complete nucleotide sequences of animal mitochondrial genomes show extensive homology in organization. The map of the human mitochondrial genome is shown in Figure 1. There are 13 protein-coding regions. All of the proteins are components of the electron transfer system of cellular respiration. These include cytochrome b, three subunits of cytochrome oxidase, one of the subunits of ATPase, and seven subunits (or associated proteins) of NADH dehydrogenase.

The fivefold discrepancy in size between the S. cerevisiae (84 kb) and mammalian (16.6 kb) mitochondrial genomes alone alerts us to the fact that there must be a great difference in their genetic organization in spite of their common function. The number of endogenously synthesized products concerned with mitochondrial enzymatic functions appears to be similar. Does the additional genetic material in yeast mitochondria encode other proteins, perhaps concerned with regulation, or is it unexpressed?

The map in FIGURE 2 accounts for the major RNA and protein products of the yeast mitochondrion. The most notable feature is the dispersion of loci on the map.

FIGURE 2. The mitochondrial genome of S. cerevisiae contains both interrupted and uninterrupted protein-coding genes, rRNA genes, and tRNA genes (positions not indicated). Arrows indicate direction of transcription.

The two largest loci are the interrupted genes box (encoding cytochrome b) and oxi3 (encoding subunit 1 of cytochrome oxidase). Together these two genes are almost as long as the entire mitochondrial genome in mammals! Many of the long introns in these genes have ORFs in register with the preceding exon . This adds several proteins, all synthesized in low amounts, to the complement of the yeast mitochondrion.

The remaining genes are uninterrupted. They correspond to the other two subunits of cytochrome oxidase encoded by the mitochondrion, to the subunit(s) of the ATPase, and (in the case of var1) to a mitochondrial ribosomal protein. The total number of yeast mitochondrial protein-coding genes is unlikely to exceed about 25.

|

|

|

|

4 أسباب تجعلك تضيف الزنجبيل إلى طعامك.. تعرف عليها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أكبر محطة للطاقة الكهرومائية في بريطانيا تستعد للانطلاق

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم السياحة الدينية: نحو 100 عجلةٍ ستشارك بنقل طلبة الجامعات خلال حفل التخرّج المركزيّ

|

|

|