تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 13-6-2017

Date: 7-6-2017

Date: 5-6-2017

|

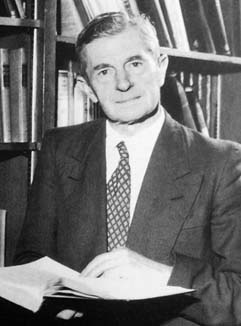

Died: 16 June 1970 in Boulder, Colorado, USA

Sydney Chapman's mother was Sarah Gray and her father was Joseph Chapman who was the chief cashier with a Manchester textile firm called Rylands. Sydney was his parents' second son and he was brought up in a very strict fashion by his Nonconformist parents.

He attended Green Lane school in Patricroft up to the age of 14. This was a good school of its type for there he learnt a little Latin and was introduced to some science subjects such as chemistry and physiology. After Sydney left school, Joseph, his father, took him to see a friend of the family who worked in engineering with the idea that his son should become an apprentice with the firm. The friend advised that he study for two further years at technical school before taking up an engineering apprenticeship.

Following this advice, Chapman entered the Royal Technical Institute, Salford (which is now the University of Salford). It was still his intention to enter the engineering industry but he performed so well at the Institute that his teachers encouraged him to sit the Lancashire Scholarship examinations. Again he had been fortunate to have been taught science subjects, although at a very low level, having a particularly good chemistry teacher. After two years at the Institute he sat the county scholarship examinations to Manchester University and was placed fifteenth, the bottom place for the award of a scholarship. He used to say in later life:-

I sometimes wonder what would have happened if I'd hit one place lower.

In 1904, at the age of 16, Sydney entered the University of Manchester and there he studied engineering in the department headed by Osborne Reynolds. In mathematics he was taught by Lamb, the professor of mathematics, and J E Littlewood who arrived from Cambridge in Chapman's final year at Manchester. Graduating with an engineering degree, he had become so fond of mathematics that he stayed on at Manchester for one further year to take a mathematics degree. At Lamb's suggestion Chapman tried for a scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge and, being successful, entered Trinity in 1908. At first he was a sizar (meaning that he obtained financial support by acting as a servant to the older boys) but from his second year onwards he received a full scholarship. Cambridge stimulated his interest more than anything had done before and perhaps this is not surprising since there he met Hardy, Whitehead and Russell [5]:-

The beauty of the place and its unspoilt surroundings came on him as a revelation, even though with his background he sometimes felt out of place. He later said that he felt that he first began to live at Cambridge.

Chapman's progress was so remarkable that he was able to start research while still an undergraduate but he was unsure whether to go in the direction of pure or applied mathematics. His first research was on summable series and he wrote two papers on this topic, one of them a joint paper with Hardy. However Larmor suggested he look at problems in the kinetic theory of gases and, despite not being very happy with the applied mathematics which Lamb had taught him, his interest soon turned in this direction.

After Chapman graduated from Cambridge in 1910 the astronomer royal, Frank Dyson, offered him the position of senior assistant at Greenwich Observatory. He accepted and continued to work there until the beginning of World War I. At first he supervised the installation of new instruments to measure magnetism, but was disappointed to find that the scientists were only interested in collecting data and were making no real attempts to interpret it. To counter this trend, Chapman began to analyse data relating to the way that the Sun and Moon influence terrestrial phenomena. His success is measured by the award of the first Smith's prize in 1913, and with this topic he began a research interest that he would continue through the rest of his life.

Chapman, however, was not entirely happy with devoting himself to astronomy as is pointed out in [5]:-

... he did not feel he was a good observer, and he did not want to subordinate all his other interests to astronomy; in particular, he wanted to complete the work he had begun on the kinetic theory of gases. Also he did not relish the prospect of the administrative work which might ultimately have fallen on him at Greenwich.

He left the Greenwich observatory and returned to Cambridge as a lecturer in 1914, with a reduced salary, around the time that World War I broke out. His religious principles made him a pacifist so he was exempted from military service and remained at Cambridge. In 1916 he was asked to return to working at the Greenwich observatory in an honorary capacity, which he did until December 1918. Once back at Cambridge after the war ended, however, he was made to feel very unhappy and unwelcome because of his pacifist views and, as a consequence, he suffered depression for a number of years.

Despite his depression Chapman's research did not suffer. During the war, between 1915 and 1917, he completed a series of important papers on thermal diffusion and the fundamentals of gas dynamics. He developed systematic approximations to the Maxwell - Boltzmann formulation for the velocity distribution function for interacting particles under general force laws. Between 1913 and 1919 he published another important series of papers, this time on terrestrial magnetism which we comment on below.

In 1919 he was appointed to the chair at Manchester where he succeeded Lamb. He married Katharine Nora Steinthal, who came from Manchester, in 1922 and they had one daughter and three sons. His career continued to go from strength to strength and he was appointed to the chair of mathematics at Imperial College London in 1924 succeeding Whitehead.

Long before the start of World War II Chapman had seen the dangers of the Nazi rise to power in Germany. His pacifist views had changed (with some considerable influence from Hitler) so that by the start of World War II he was ready to undertake war service and he worked on military operational research and incendiary bomb problems.

In 1945, at the end of World War II, he returned to his chair in London but was now less happy than he had been, so, in 1946, he readily accepted the offer of the Sedleian Chair of Natural Philosophy at Oxford, also becoming a fellow of Queen's College at this time. The next few years turned out to be the least productive period in Chapman's research career. Science was considered of secondary importance in Oxford at the time, and he worked hard to convince non-scientists of its importance by teaching special lecture courses for non-scientists.

He resigned his position in Oxford in 1953 at age 65, rather than waiting to retire at age 70, and began to visit many places throughout the world. In particular he took a research post in Alaska in 1953 and in addition took on a similar post at the High Altitude Observatory in Boulder, Colorado, two years later. These became his two main bases, but his visits to other places included Michigan and Minnesota in the USA, Istanbul, Ibadan, Cairo, Prague, Tokyo and Russia.

Chapman's main area of research was the Earth's magnetic field and for his work in this area he was elected to the Royal Society in 1919, and awarded the Society's Copley Medal in 1966:-

... in recognition of his theoretical contributions to terrestrial and interplanetary magnetism, the ionosphere and the aurora borealis.

He had begun work on geomagnetism in 1913 and between then and 1915 had published three papers on the topic. These interpreted magnetic variations using a dynamo theory driven by tidal flows in the ionosphere resulting from the influence of the Sun and Moon. In 1919 he produced the first theory which attempted to explain magnetic storms, but he soon found that it was unsound. He received the Adams Prize in 1928 for an essay on geomagnetism. Other work which he did around this time was undertaken in collaboration with Milne.

Between 1928 and 1932 Chapman returned to work on gas dynamics, extending the methods he had developed earlier. He also undertook important research on plasmas. In 1931 he gave the Royal Society Bakerian lecture which was a classic in which he developed the now standard layer theory for the lower ionosphere. He was honoured in 1957 by being elected president of the Special Commission of the International Geophysical Year. In fact he played a major role in initiating and guiding the International Geophysical Year which has been the greatest international geophysics cooperation of the twentieth century.

Chapman, when asked shortly before his death which work he had undertaken since retiring he had found most interesting, replied that it was his work on thermal diffusion in highly ionised gases, his work on magnetic storms, his work on instability along magnetic neutral lines, and his work on noctilucent clouds.

Cowling writes in [5] about his lecturing style:-

His lecturing style tended to be pedestrian, though workmanlike. ... Thus when I first heard Chapman lecture at the British Association in 1931, I was at first disappointed; not until later did I appreciate how packed with relevant information his talk had been. There was a simple directness about his mode of expression, which often concealed deep thought.

His personal characteristics are described in [5] as follows:-

Those who knew Chapman all testify to his kindness, persistence, simplicity and integrity. His kindliness was appreciated by successive generations of research students and junior colleagues, in times of difficulty one could always turn to him for helpful advice.

His character and interests are also described in [3]:-

Chapman's mild manner veiled a strong will and great determination; his tastes and habits were simple. He was an enthusiastic cyclist, swimmer and walker, and both on his visits to foreign universities or to international conferences, however varied the available modes of transport might be, Chapman could always be relied on to arrive on a bicycle. He rode from Montreal to Washington in 1939 to attend the meeting of the International Geophysical Union.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتبة أمّ البنين النسويّة تصدر العدد 212 من مجلّة رياض الزهراء (عليها السلام)

|

|

|