Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-11-07

Date: 2024-10-26

Date: 2024-10-17

|

The words vowel and consonant are very familiar ones, but when we study the sounds of speech scientifically we find that it is not easy to define exactly what they mean. The most common view is that vowels are sounds in which there is no obstruction to the flow of air as it passes from the larynx to the lips. A doctor who wants to look at the back of a patient's mouth often asks them to say "ah"; making this vowel sound is the best way of presenting an unobstructed view. But if we make a sound like s, d it can be clearly felt that we are making it difficult or impossible for the air to pass through the mouth. Most people would have no doubt that sounds like s, d should be called consonants. However, there are many cases where the decision is not so easy to make. One problem is that some English sounds that we think of as consonants, such as the sounds at the beginning of the words 'hay' and 'way', do not really obstruct the flow of air more than some vowels do. Another problem is that different languages have different ways of dividing their sounds into vowels and consonants; for example, the usual sound produced at the beginning of the word 'red' is felt to be a consonant by most English speakers, but in some other languages (e.g. Mandarin Chinese) the same sound is treated as one of the vowels.

If we say that the difference between vowels and consonants is a difference in the way that they are produced, there will inevitably be some cases of uncertainty or disagreement; this is a problem that cannot be avoided. It is possible to establish two distinct groups of sounds (vowels and consonants) in another way. Consider English words beginning with the sound h; what sounds can come next after this h? We find that most of the sounds we normally think of as vowels can follow (e.g. e in the word 'hen'), but practically none of the sounds we class as consonants, with the possible exception of j in a word such as 'huge' hju:ʤ. Now think of English words beginning with the two sounds bI; we find many cases where a consonant can follow (e.g. d in the word 'bid', or l in the word 'bill'), but practically no cases where a vowel may follow. What we are doing here is looking at the different contexts and positions in which particular sounds can occur; this is the study of the distribution of the sounds, and is of great importance in phonology. Study of the sounds found at the beginning and end of English words has shown that two groups of sounds with quite different patterns of distribution can be identified, and these two groups are those of vowel and consonant. If we look at the vowel-consonant distinction in this way, we must say that the most important difference between vowel and consonant is not the way that they are made, but their different distributions. It is important to remember that the distribution of vowels and consonants is different for each language.

We begin the study of English sounds in this course by looking at vowels, and it is necessary to say something about vowels in general before turning to the vowels of English. We need to know in what ways vowels differ from each other. The first matter to consider is the shape and position of the tongue. It is usual to simplify the very complex possibilities by describing just two things: firstly, the vertical distance between the upper surface of the tongue and the palate and, secondly, the part of the tongue, between front and back, which is raised highest. Let us look at some examples:

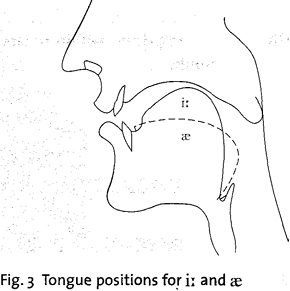

i) Make a vowel like the i: in the English word 'see' and look in a mirror; if you tilt your head back slightly you will be able to see that the tongue is held up close to the roof of the mouth. Now make an { vowel (as in the word 'cat') and notice how the distance between the surface of the tongue and the roof of the mouth is now much greater. The difference between i: and as is a difference of tongue height, and we would describe i: as a relatively close vowel and as as a relatively open vowel. Tongue height can be changed by moving the tongue up or down, or moving the lower jaw up or down. Usually we use some combination of the two sorts of movement, but when drawing side-of-the-head diagrams such as Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 it is usually found simpler to illustrate tongue shapes for vowels as if tongue height were altered by tongue movement alone, without any accompanying jaw movement. So we would illustrate the tongue height difference between i: and æ as in Fig. 3.

ii) In making the two vowels described above, it is the front part of the tongue that is raised. We could therefore describe i: and æ as comparatively front vowels. By changing the shape of the tongue we can produce vowels in which a different part of the tongue is the highest point. A vowel in which the back of the tongue is the highest point is called a back vowel. If you make the vowel in the word 'calm', which we write phonetically as ɑ:, you can see that the back of the tongue is raised. Compare this with { in front of a mirror; as is a front vowel and a: is a back vowel. The vowel in 'too' (u:) is also a comparatively back vowel, but compared with a: it is close.

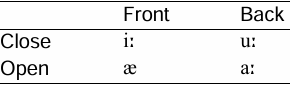

So now we have seen how four vowels differ from each other; we can show this in a simple diagram.

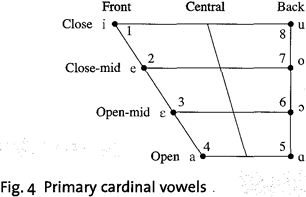

However, this diagram is rather inaccurate. Phoneticians need a very accurate way of classifying vowels, and have developed a set of vowels which are arranged in a close-open, front-back diagram similar to the one above but which are not the vowels of any particular language. These cardinal vowels are a standard reference system, and people being trained in phonetics at an advanced level have to learn to make them accurately and recognize them correctly. If you learn the cardinal vowels, you are not learning to make English sounds, but you are learning about the range of vowels that the human vocal apparatus can make, and also learning a useful way of describing, classifying and comparing vowels. They are recorded on Track 21 of CD 2.

It has become traditional to locate cardinal vowels on a four-sided figure (a quadrilateral of the shape seen in Fig. 4 - the design used here is the one recommended by the International Phonetic Association). The exact shape is not really important - a square would do quite well - but we will use the traditional shape. The vowels in Fig. 7 are the so- called primary cardinal vowels; these are the vowels that are most familiar to the speakers of most European languages, and there are other cardinal vowels (secondary cardinal vowels) that sound less familiar. In this course cardinal vowels are printed within square brackets [ ] to distinguish them clearly from English vowel sounds.

Cardinal vowel no. 1 has the symbol [i], and is defined as the vowel which is as close and as front as it is possible to make a vowel without obstructing the flow of air enough to produce friction noise; friction noise is the hissing sound that one hears in consonants like s or f. Cardinal vowel no. 5 has the symbol [a] and is defined as the most open and back vowel that it is possible to make. Cardinal vowel no. 8 [u] is fully close and back and no. 4 [a] is fully open and front. After establishing these extreme points, it is possible to put in intermediate points (vowels no. 2, 3, 6 and 7). Many students when they hear these vowels find that they sound strange and exaggerated; you must remember that they are extremes of vowel quality. It is useful to think of the cardinal vowel framework like a map of an area or country that you are interested in. If the map is to be useful to you it must cover all the area; but if it covers the whole area of interest it must inevitably go a little way beyond that and include some places that you might never want to go to.

When you are familiar with these extreme vowels, you have (as mentioned above) learned a way of describing, classifying and comparing vowels. For example, we can say that the English vowel { (the vowel in 'cat') is not as open as cardinal vowel no. 4 [a]. We have now looked at how we can classify vowels according to their tongue height and their frontness or backness. There is another important variable of vowel quality, and that is lip-position. Although the lips can have many different shapes and positions, we will at this stage consider only three possibilities. These are:

i) Rounded, where the corners of the lips are brought towards each other and the lips pushed forwards. This is most clearly seen in cardinal vowel no. 8 [u].

ii) Spread, with the corners of the lips moved away from each other, as for a smile. This is most clearly seen in cardinal vowel no. 1 [i].

iii) Neutral, where the lips are not noticeably rounded or spread. The noise most English people make when they are hesitating (written 'er') has neutral lip position.

Now, using the principles that have just been explained, we will examine some of the English vowels.

|

|

|

|

لخفض ضغط الدم.. دراسة تحدد "تمارين مهمة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

طال انتظارها.. ميزة جديدة من "واتساب" تعزز الخصوصية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مشاتل الكفيل تزيّن مجمّع أبي الفضل العبّاس (عليه السلام) بالورد استعدادًا لحفل التخرج المركزي

|

|

|