Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-08-10

Date: 2024-07-17

Date: 14-2-2022

|

We have dealt with the syntactic repercussions of factivity in sentential complementation. This is really an artificially delimited topic (as almost all topics in linguistics necessarily are). Factivity is relevant to much else in syntax besides sentential complementation, and on the other hand, the structure of sentential complementation is naturally governed by different semantic factors which interact with factivity. That is one source of the painful gaps in the above presentation which the reader will surely have noticed. We conclude by listing summarily a couple of possible additional applications of factivity, and some additional semantic factors which determine the form of complements, in order at least to hint at some ways in which the gaps can be filled, and to suggest what seem to us promising extensions of the approach we have taken.

(1) There is a syntactic and semantic correspondence between truth and specific reference. The verbs which presuppose that their sentential object expresses a true proposition also presuppose that their non-sentential object refers to a specific thing. For example, in the sentences

I ignored an ant on my plate

I imagined an ant on my plate

the factive verb ignore presupposes that there was an ant on my plate, but the non-factive verb imagine does not. Perhaps this indicates that at some sufficiently abstract level of semantics, truth and specific reference are reducible to the same concept. Frege’s speculations that the reference of a sentence is its truth value would thereby receive some confirmation.

Another indication that there is a correspondence between truth of propositions and specific reference of noun phrases is the following. We noted that extraposition is obligatory for non-factive subject complements. Compare -

That John has come makes sense (factive)

*That John has come seems (non-factive)

where the second sentence must become

It seems that John has come

unless it undergoes subject-raising. This circumstance appears to reflect a more general tendency for sentence-initial clauses to get understood factively. For example, in saying

The UPI reported that Smith had arrived

It was reported by the UPI that Smith had arrived

the speaker takes no stand on the truth of the report. But

The Smith had arrived was reported by the UPI

normally conveys the meaning that the speaker assumes the report to be true. A non-factive interpretation of this sentence can be teased out in various ways, for example by laying contrastive stress on the agent phrase (by the UPI, not the AP). Still, the unforced sense is definitely factive. These examples are interesting because they suggest that the factive vs. non-factive senses of the complement do not really correspond to the application of any particular transformation, but rather to the position of the complement in the surface structure. The interpretation can be non-factive if both passive and extraposition have applied, or if neither of them has applied; if only the passive has applied, we get the factive interpretation. This is very hard to state in terms of a condition on transformations. It is much easier to say that the initial position itself of a clause is in such cases associated with a factive sense.

This is where the parallelism between truth and specific reference comes in. The problem with the well-known pairs like

Everyone in this room speaks two languages

Two languages are spoken by everyone in this room

is exactly that indefinite noun phrases such as two languages are understood as referring to specific objects when placed initially (‘ there are two languages such that. . . ’). Again, it is not on the passive itself that the meaning depends. In the sentence

Two languages are familiar to everyone in this room

the passive has not applied, but two languages is again understood as specific because of its initial position.

(2) We also expect that factivity will clarify the structure of other types of subordinate clauses. We have in mind the difference between purpose clauses (non-factive) and result clauses (factive), and different types of conditional and concessive clauses.

(3) There are languages which distinguish factive and non-factive moods in de¬ clarative sentences. For example, in Hidatsa (Matthews 1964) there is a factive mood whose use in a sentence implies that the speaker is certain that the sentence is true, and a range of other moods indicating hearsay, doubt, and other judgments of the speaker about the sentence. While this distinction is not overt in English, it seems to us that it may be sensed in an ambiguity of declarative sentences. Consider the statement

He’s an idiot.

There is an ambiguity here which may be resolved in several ways. For example, the common question

Is that a fact or is that just your opinion?

(presumably unnecessary in Hidatsa) is directed exactly at disambiguating the statement. The corresponding why-question -

Why is he an idiot?

may be answered in two very different ways, e.g.

(a) Because his brain lacks oxygen

(b) Because he failed this simple test for the third time.

There are thus really two kinds of why-questions: requests for explanation, which pre¬ suppose the truth of the underlying sentence, and requests for evidence, which do not. The two may be paraphrased

(a) Why is it a fact that he is an idiot?

(b) Why do you think that he is an idiot?

(4) Consider the sentences

John’s eating them would amaze me

I would like John’s doing so.

These sentences do not at all presuppose that the proposition in the complement is true. This indicates a further complexity of the fact postulated in the deep structure of factive complements. Like verbs, 01 predicates in general, it appears to take various tenses or moods. Note that there correspond to the above sentences:

If he were to eat them it would amaze me

I would like it if John were to do so.

These can also be construed as

If it were a fact that he ate them it would amaze me.

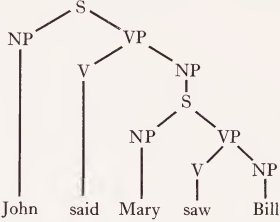

A second oversimplification may be our assumption that sentences are embedded in their deep structure form. A case can be made for rejecting this customary approach in favor of one where different verbs take complements at different levels of representation. Consider direct quotation, which appears not to have been treated in generative grammar. The fundamental fact is that what one quotes are surface structures and not deep structures. That is, if John’s words were ‘Mary saw Bill’, then we can correctly report

John said: ‘Mary saw Bill’

but we shall have misquoted him if we say

John said: ‘Bill was seen by Mary’

If we set up the deep structure of both sentences simply as

then we have not taken account of this fact. We should be forced to add to this deep structure the specification that the complement either must or cannot undergo the passive, depending on which of the sentences we are quoting. Since sentences of any complexity can be quoted, to whose deep structures the passive and other optional transformations may be applicable an indefinite number of times, it is not enough simply to mark the embedded deep structure of the quoted sentence as a whole for applicability of transformations. What has to be indicated according to this solution is the whole transformational history of the quoted sentence.

A more natural alternative is to let the surface structure itself of the quoted sentence be embedded. This would be the case in general for verbs taking direct quotes. Other classes of verbs would take their complements in different form. We then notice that the initial form of a complement can in general be selected at a linguistically functional level of representation in such a way that the truth value of the whole sentence will not be altered by any rules which are applicable to the complement. Assuming a generative semantics, the complements of verbs of knowing and believing are then semantic representations. From

John thinks that the McCavitys are a quarrelsome bunch of people

it follows that

John thinks that the McCavitys like to pick a fight.

That is, one believes propositions and not sentences. Believing a proposition in fact commits one to believing what it implies: if you believe that Mary cleaned the room you must believe that the room was cleaned. (Verbs like regret, although their objects are also propositions, differ in this respect. If you regret that Mary cleaned the room you do not necessarily regret that the room was cleaned.)

At the other extreme would be cases of phonological complementation, illustrated by the context

John went ‘ — ’.

The object here must be some actual noise or a conventional rendering thereof such as ouch or plop.

A good many verbs can take complements at several levels. A verb like scream, which basically takes phonological complements, can be promoted to take direct quotes. Say seems to take both of these and propositions as well.

Are there verbs which require their complement sentences to be inserted in deep structure form (in the sense of Chomsky) ? Such a verb X would have the property that

John Xed that Bill entered the house,

would imply that

John Xed that the house was entered by Bill

but would not imply that

John Xed that Bill went into the house.

That is, the truth of the sentence would be preserved if the object clause underwent a different set of optional transformations, but not if it was replaced by a paraphrase with another deep structure source. It is an interesting question whether such verbs exist. We have not been able to find any. Unless further search turns up verbs of this kind, we shall have to conclude that, if the general idea proposed here is valid, the levels of semantics, surface structure, and phonology, but not the level of deep structure, can function as the initial representation of complements.

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يختتم مسابقة دعاء كميل

|

|

|