Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

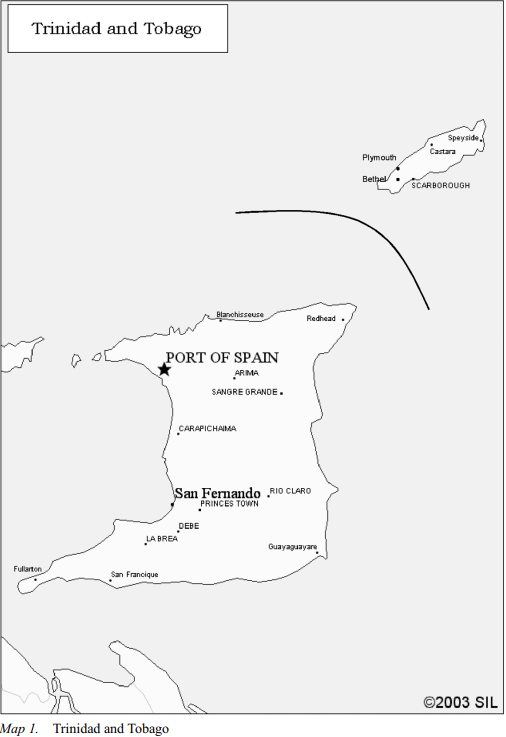

Reading Comprehension| The creoles of Trinidad and Tobago: phonology Sociohistorical background |

|

|

|

Read More

Date: 2025-03-12

Date: 2024-05-15

Date: 2024-12-31

|

The histories of the islands of Trinidad and Tobago are divergent, and although the two have comprised a single political entity since 1889, they must be considered as separate entities for the purposes of describing both their histories and the distinct linguistic elements in their language varieties. This need has been under-stated in the literature on Trinidad and Tobago, since the two islands have hardly been treated differentially in any detail in survey texts (e.g., Holm 1989/90; Winford 1993).

Solomon (1993: 2) mentions a paucity of information available on Tobago, but there has been work (e.g. James 1974; Minderhout 1979; Southers 1977) which has simply drawn less attention to itself because of the political ascendancy of the larger island. It is hoped that a new publication on Tobagonian will redress the balance (James and Youssef 2002), since the basilectal variety peculiar to Tobago alone merits attention in its own right, and the interplay among varieties in the island is also unique. For phonology, this is undisputably the most comprehensive source. The best sources on the phonology of Trinidad are Winford (1972, 1978), Winer (1993) and Solomon (1993).

Broadly it can be said that the history of conquest, exploitation and migration was different for Trinidad and Tobago, notwithstanding their common Amerindian indigenous base and initial Spanish incursions. Both were claimed by Columbus in 1498, but Tobago was sighted and not invaded at this time. However, Trinidad remained officially Spanish until 1797, with a strong French presence up to the late-eighteenth century, while Tobago was continuously squabbled over until 1763, but with no lasting linguistic impact either from Spanish or French. The difference was one of skirmishes in Tobago versus long-lasting settlement in Trinidad, with the latter having more far-reaching linguistic results on the lexicon.

With regard to the history and development of Caribbean creole languages generally, there is likely to have been a spectrum of language varieties from the outset. A full language continuum ranging from the basilectal creole to the standard is likely to have developed in early slave societies according to the extent of exposure of different sub-groups in the society to the Standard. House slaves are likely to have developed near-acrolectal varieties, whereas the field slaves would have developed and continued to use the basilect. Field slaves were cut off from real social contact with the ruling class or from any motivation to move towards its language. Children born into the society would have heard their parents’ native African languages as well as interlanguage varieties adopted by the adults as they made more or less accommodation to the superstrate languages. In some measure, it would have been these children who would have augmented their parents’ language creation, becoming the ultimate architects of the new creole language.

|

|

|

|

دخلت غرفة فنسيت ماذا تريد من داخلها.. خبير يفسر الحالة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ثورة طبية.. ابتكار أصغر جهاز لتنظيم ضربات القلب في العالم

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

سماحة السيد الصافي يؤكد ضرورة تعريف المجتمعات بأهمية مبادئ أهل البيت (عليهم السلام) في إيجاد حلول للمشاكل الاجتماعية

|

|

|