Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-11-20

Date: 2023-04-26

Date: 2023-11-24

|

Semantic features

The terminology above provides a useful toolkit for the description of sense relations between lexemes, but does not amount to anything resembling a theory of semantics or to an understanding of how meaning is constructed at the lexical level. We have seen how sentences can be broken down into constituents, morphemes, and ultimately phonemes: might meaning, too, be analyzed in terms of more basic semantic components? This is the principle behind an approach to semantics known as componential analysis, which starts from the assumption that meanings can be decomposed into bundles of binary semantic features, comparable to the distinctive features of phonology. For example, dog and puppy might be distinguished by their specification for the feature ±[ADULT], dog being +[ADULT] and puppy –[ADULT]; similarly, the distinction between dog and bitch could be captured by a feature ±[MALE] or ±[FEMALE]. These features could be used to distinguish man/ woman/boy/girl; father/mother; duck/drake/duckling and so on, while ±[HUMAN] could be used to differentiate man, woman, grandmother from animals, all of which could be distinguished from non-living things, such as book, lamp, car, by ±[ANIMATE].

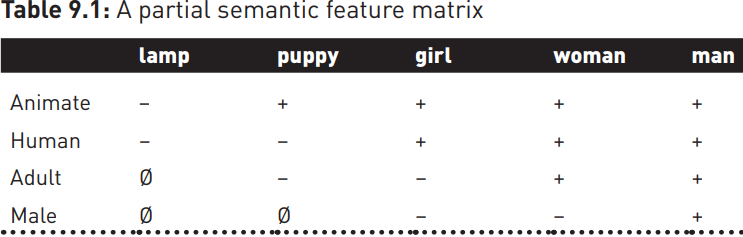

A partial feature matrix based on these features is illustrated below. Note that +[HUMAN] entails +[ANIMATE], and only items marked +[ANIMATE] can have a specification for +/-[ADULT] or +/-[MALE]. The symbol Ø indicates that a lexeme is unspecified for a particular feature.

This approach has a number of theoretical attractions. Firstly, it offers a technical definition for many of the sense relations we explored earlier. A hyponym, for example, can be said to contain all the features of its hypernym, and some more besides: while person, for example, is +[ANIMATE], +[HUMAN], woman is additionally –[MALE] or +[FEMALE] according to the feature system employed. Features can also capture common relationships between sets of lexemes in the same way as distinctive features in phonology capture the relationships between pairs of sounds. So, just as the members of the pairs /b/-/p/, /g/-/k/, /d/-/t/ differ in their specification for the feature ±[VOICE], so dog-puppy, woman-girl, horse-foal, pig-piglet differ in their specification for the semantic feature ±[ADULT], the former of each pair having a positive and the latter a negative value.

Semantic features can help refine our grammatical description, too. Consider the examples below:

1 *Much coins

2 ?Two muds

3 The pelican read the newspaper.

The ungrammaticality of the first example could be explained by a requirement that the quantifier much can only collocate with nouns having a negative value for the feature ±[COUNT]. Similarly, for example 2, nouns marked –[COUNT] cannot normally be collocated with numerals, or with many. Where they are, as in this case, the hearer will try where possible to reinterpret the noun itself as +[COUNT] and meaning ‘type of’ (hence ‘two good wines’, ‘my three favorite cheeses’). Finally, example 3 is perfectly grammatical according to the syntax of English, but pragmatically odd. The oddity could be explained by positing a specification for the verb to read that its subject will be marked +[HUMAN]: this requirement could only be overridden in a fictional or hypothetical world in which pelicans can and do read newspapers.

Similarly, we could posit within a grammar of English a feature ±[SOLID] associated with nouns such as timber, wood, paper, glass, and require of verbs like cut, sever, rip, knock, tap or drill that they collocate only with nouns with a positive value for this feature, thereby ruling out *he severed the water or *he knocked on the gas. Regularities between verbs such as kill, cultivate, incite, inspire might be explored using a meaning component ±[CAUSE]: kill, for example, has been analyzed as +[CAUSE] +[COME ABOUT] –[ALIVE]. Hopes were raised that, as in phonology, meaning might be reducible to a basic set of semantic features or meaning primes, applicable to all natural languages.

For all their initial promise, semantic features soon proved to be limited in their theoretical scope. Let us return again to nouns in our table above, which we noted were only partly specified. Puppy is +[ANIMATE], –[HUMAN], –[ADULT], but this specification would do also for kitten, duckling, foal, cub, and the young of other animals. Likewise, the specification –[ANIMATE], –[HUMAN], for lamp would fit any inanimate object we cared to name. To distinguish, for example, puppy and kitten we have to posit a specific feature for each, perhaps ±[CANINE] or ±[FELINE], but these begin to look more like ad hoc creations for the relevant lexical sets (dog/mongrel/bitch/spaniel… and cat/tabby/moggy/ tiger… respectively), rather than genuine semantic primes with explanatory power outside a restricted domain.

In similar vein, a partial feature analysis for the verb assassinate might be +[CAUSE], +[COME ABOUT] –[ALIVE] as suggested above for kill, but we would have to specify that its object be marked +[IMPORTANT PUBLIC FIGURE] or suchlike to capture, however approximately, the difference between the two verbs, which again looks a little contrived and is not obviously generalizable to other lexical items. More complex still would be a feature specification to distinguish the connotative meanings of sweat and perspiration, for example, or the distinction between the verbs demand, ask and request.

Extending the concept of semantic features beyond a promising but small number of putative semantic ‘primes’ leads to a proliferation of features applicable only to individual lexical items, and a feature set which is in fact almost as large as the lexicon itself. We are, in effect, doing little more than offering fancy formal definitions for the words involved. Semantics ultimately seems too culture-specific for a universal feature set to be applicable and semantic features which are important in one language may not be in another. As we saw, Dyirbal has a semantically motivated noun class for ‘women, fire and dangerous things’, while in Navajo, a native American language spoken in Southern USA, verbal suffixes vary according to whether the noun object is + or –[FLEXIBLE].

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتبة أمّ البنين النسويّة تصدر العدد 212 من مجلّة رياض الزهراء (عليها السلام)

|

|

|