تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 11-10-2015

Date: 11-10-2015

Date: 11-10-2015

|

The use of trigonometric functions arises from the early connection between mathematics and astronomy. Early work with spherical triangles was as important as plane triangles.

The first work on trigonometric functions related to chords of a circle. Given a circle of fixed radius, 60 units were often used in early calculations, then the problem was to find the length of the chord subtended by a given angle. For a circle of unit radius the length of the chord subtended by the angle x was 2sin (x/2). The first known table of chords was produced by the Greek mathematician Hipparchus in about 140 BC. Although these tables have not survived, it is claimed that twelve books of tables of chords were written by Hipparchus. This makes Hipparchus the founder of trigonometry.

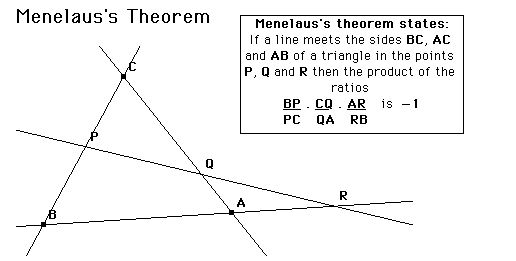

The next Greek mathematician to produce a table of chords was Menelaus in about 100 AD. Menelaus worked in Rome producing six books of tables of chords which have been lost but his work on spherics has survived and is the earliest known work on spherical trigonometry. Menelaus proved a property of plane triangles and the corresponding spherical triangle property known the regula sex quantitatum.

Ptolemy was the next author of a book of chords, showing the same Babylonian influence as Hipparchus, dividing the circle into 360° and the diameter into 120 parts. The suggestion here is that he was following earlier practice when the approximation 3 for π was used. Ptolemy, together with the earlier writers, used a form of the relation sin2 x + cos2 x = 1, although of course they did not actually use sines and cosines but chords.

Similarly, in terms of chords rather than sin and cos, Ptolemy knew the formulas

sin(x + y) = sinx cos y + cosx sin y

a/sin A = b/sin B = c/sin C.

Ptolemy calculated chords by first inscribing regular polygons of 3, 4, 5, 6 and 10 sides in a circle. This allowed him to calculate the chord subtended by angles of 36°, 72°, 60°, 90° and 120°. He then found a method of finding the cord subtended by half the arc of a known chord and this, together with interpolation allowed him to calculate chords with a good degree of accuracy. Using these methods Ptolemy found that sin 30' (30' = half of 1°) which is the chord of 1° was, as a number to base 60, 0 31' 25". Converted to decimals this is 0.0087268 which is correct to 6 decimal places, the answer to 7 decimal places being 0.0087265.

The first actual appearance of the sine of an angle appears in the work of the Hindus. Aryabhata, in about 500, gave tables of half chords which now really are sine tables and used jya for our sin. This same table was reproduced in the work of Brahmagupta (in 628) and detailed method for constructing a table of sines for any angle were give by Bhaskara in 1150.

The Arabs worked with sines and cosines and by 980 Abu'l-Wafa knew that

sin 2x = 2 sin x cos x

although it could have easily have been deduced from Ptolemy's formula sin(x + y) = sin x cos y + cos x sin y with x = y.

The Hindu word jya for the sine was adopted by the Arabs who called the sine jiba, a meaningless word with the same sound as jya. Now jiba became jaib in later Arab writings and this word does have a meaning, namely a 'fold'. When European authors translated the Arabic mathematical works into Latin they translated jaib into the word sinus meaning fold in Latin. In particular Fibonacci's use of the term sinus rectus arcus soon encouraged the universal use of sine.

Chapters of Copernicus's book giving all the trigonometry relevant to astronomy was published in 1542 by Rheticus. Rheticus also produced substantial tables of sines and cosines which were published after his death. In 1533 Regiomontanus's work De triangulis omnimodis was published. This contained work on planar and spherical trigonometry originally done much earlier in about 1464. The book is particularly strong on the sine and its inverse.

The term sine certainly was not accepted straight away as the standard notation by all authors. In times when mathematical notation was in itself a new idea many used their own notation. Edmund Gunter was the first to use the abbreviation sin in 1624 in a drawing. The first use of sin in a book was in 1634 by the French mathematician Hérigone while Cavalieri used Si and Oughtred S.

It is perhaps surprising that the second most important trigonometrical function during the period we have discussed was the versed sine, a function now hardly used at all. The versine is related to the sine by the formula

versin x = 1 - cos x.

It is just the sine turned (versed) through 90°.

The cosine follows a similar course of development in notation as the sine. Viète used the term sinus residuae for the cosine, Gunter (1620) suggested co-sinus. The notation Si.2 was used by Cavalieri, s co arc by Oughtred and S by Wallis.

Viète knew formulas for sin nx in terms of sin x and cos x. He gave explicitly the formulas (due to Pitiscus)

sin 3x = 3 cos 2x sin x - sin 3 x

cos 3x = cos 3x - 3 sin 2x cos x.

The tangent and cotangent came via a different route from the chord approach of the sine. These developed together and were not at first associated with angles. They became important for calculating heights from the length of the shadow that the object cast. The length of shadows was also of importance in the sundial. Thales used the lengths of shadows to calculate the heights of pyramids.

The first known tables of shadows were produced by the Arabs around 860 and used two measures translated into Latin as umbra recta and umbra versa. Viète used the terms amsinus and prosinus. The name tangent was first used by Thomas Fincke in 1583. The term cotangens was first used by Edmund Gunterin 1620.

Abbreviations for the tan and cot followed a similar development to those of the sin and cos. Cavalieri used Ta and Ta.2, Oughtred used t arc and t co arc while Wallis used T and t. The common abbreviation used today is tan by we write tan whereas the first occurrence of this abbreviation was used by Albert Girard in 1626, but tan was written over the angle tan A

cot was first used by Jonas Moore in 1674.

The secant and cosecant were not used by the early astronomers or surveyors. These came into their own when navigators around the 15th Century started to prepare tables. Copernicus knew of the secant which he called the hypotenusa. Viète knew the results

cosec x/sec x = cot x = 1/tan x

1/cosec x = cos x/cot x = sin x.

The abbreviations used by various authors were similar to the trigonometric functions already discussed. Cavalieri used Se and Se.2, Oughtred used se arc and sec co arc while Wallis used s and σ. Albert Girard used sec, written above the angle as he did for the tan.

The term 'trigonometry' first appears as the title of a book Trigonometria by B Pitiscus, published in 1595. Pitiscus also discovered the formulas for sin 2x, sin 3x, cos 2x, cos 3x.

The 18th Century saw trigonometric functions of a complex variable being studied. Johann Bernoulli found the relation between sin-1z and log z in 1702 while Cotes, in a work published in 1722 after his death, showed that

ix = log(cos x + i sin x ).

De Moivre published his famous theorem

(cos x + i sin x )n = cos nx + i sin nx

in 1722 while Euler, in 1748, gave the formula (equivalent to that of Cotes)

exp(ix) = cos x + i sin x .

The hyperbolic trigonometric functions were introduced by Lambert.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي ينظّم ندوة حوارية حول مفهوم العولمة الرقمية في بابل

|

|

|