Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-09-22

Date: 2023-05-20

Date: 28-1-2022

|

The overall conclusion to be drawn from our discussion is that all finite clauses (whether main clauses or complement clauses) are CPs headed by an (overt or null) complementizer which marks the force of the clause. But what about non-finite clauses? It seems clear that for-to infinitive clauses such as that bracketed in (64) below are CPs since they are introduced by the infinitival complementizer for:

But what about the type of (bracketed) infinitive complement clause found after verbs like want in sentences such as (65) below?

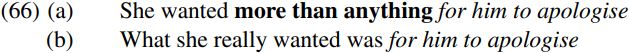

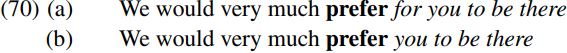

At first sight, it might seem as if the bracketed complement clause in sentences like (65) can’t be a CP, since it isn’t introduced by the infinitival complementizer for. However, it is interesting to note that the complement of want is indeed introduced by for when the infinitive complement is separated from the verb want in some way – e.g. when there is an intervening adverbial expression like more than anything as in (66a) below, or when the complement of want is in focus position in a pseudo-cleft sentence as in (66b):

(Pseudo-cleft sentences are sentences such as ‘What John bought was a car’, where the italicized expression is said to be focused and to occupy focus position within the sentence.) This makes it plausible to suggest that the complement of want in structures like (65) is a CP headed by a null variant of for (below symbolized as  ), so that (65) has the skeletal structure (67) below (simplified by showing only those parts of the structure immediately relevant to the discussion at hand):

), so that (65) has the skeletal structure (67) below (simplified by showing only those parts of the structure immediately relevant to the discussion at hand):

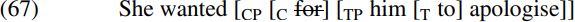

We can then say that the infinitive subject him is assigned accusative case by the complementizer  in structures like (67) in exactly the same way as the accusative subject them is assigned accusative case by the complementizer for in the bracketed complement clause in (64). (How case-marking works will be discussed) One way of accounting for why the complementizer isn’t overtly spelled out as for in structures like (67) is to suppose that it is given a null spellout (and thereby has its phonetic features deleted) when introducing the complement of a verb like want: we can accordingly refer to verbs like want as for-deletion verbs. For speakers of varieties of English such as mine, for-deletion is obligatory when the for-clause immediately follows a verb like want, but cannot apply when the for-clause is separated from want in some way – as the examples below illustrate:

in structures like (67) in exactly the same way as the accusative subject them is assigned accusative case by the complementizer for in the bracketed complement clause in (64). (How case-marking works will be discussed) One way of accounting for why the complementizer isn’t overtly spelled out as for in structures like (67) is to suppose that it is given a null spellout (and thereby has its phonetic features deleted) when introducing the complement of a verb like want: we can accordingly refer to verbs like want as for-deletion verbs. For speakers of varieties of English such as mine, for-deletion is obligatory when the for-clause immediately follows a verb like want, but cannot apply when the for-clause is separated from want in some way – as the examples below illustrate:

It would seem, therefore, that for-deletion is subject to much the same strict adjacency requirement as that-deletion. Since have-cliticisation is subject to much the same conditions, it may be that for-deletion somehow involves the complementiser cliticising to the verb want and thereby being given a null spellout (in much the same way as in African American English/AAE sentences like (25) He gonna be there, I know he is, the form is has a null spellout only in contexts where in Standard English/SE it would cliticise to a host, so that SE He’s gonna corresponds to AAE He gonna).

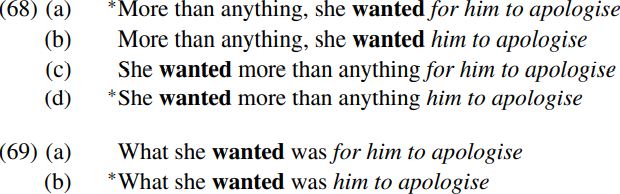

Interestingly, not all for-deletion verbs behave exactly like want: for example, in my variety of English the verb prefer optionally (rather than obligatorily) allows deletion of for when it immediately follows prefer – cf.:

The precise conditions on when for can or cannot be deleted are unclear: there are complex lexical factors at work here (in that e.g. words like want and prefer may behave differently in a particular variety of English) and also complex sociolinguistic factors (in that there is considerable dialectal variation with respect to the use of for in infinitive complement clauses).

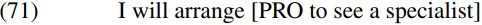

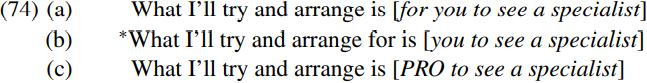

Having looked at for-deletion verbs which select an infinitival complement with an accusative subject, let’s now consider the syntax of control infinitive clauses with a null PRO subject like that bracketed in (71) below:

What we shall argue here is that control clauses which have a null PRO subject are introduced by a null infinitival complementizer. However, the null complementizer introducing control clauses differs from the null complementizer found in structures like want/prefer someone to do something in that it never surfaces as an overt form like for, and hence is inherently null. There is, however, parallelism between the structure of a for infinitive clause like that bracketed in (64) above, and that of a control infinitive clause like that bracketed in (71), in that they are both CPs and have a parallel internal structure, as shown in (72a,b) below (simplified by not showing the internal structure of the verb phrase see a specialist):

The two types of clause thus have essentially the same CP+TP+VP structure, and differ only in that a for infinitive clause like (72a) has an overt for complementizer and an overt accusative subject like them, whereas a control infinitive clause like (72b) has a null ø complementizer and a null PRO subject.

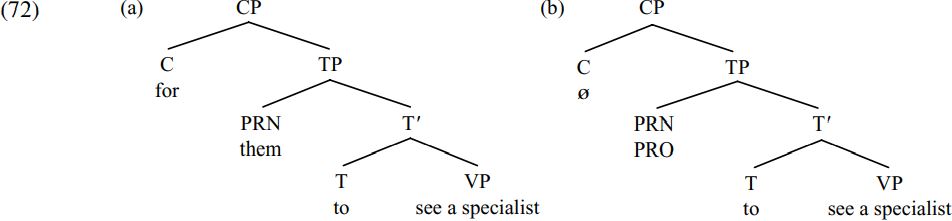

Some evidence in support of claiming that a control clause with a null PRO subject is introduced by a null complementizer comes from coordination facts in relation to sentences such as the following:

The fact that the italicized control infinitive can be conjoined with the bold-printed CP headed by for suggests that control infinitives must be CPs (if only the same types of constituent can be conjoined).

Further evidence in support of the CP status of control infinitives comes from the fact that they can be focused in pseudo-cleft sentences. In this connection, consider the contrast below:

The grammaticality of (74a) suggests that a CP like for you to see a specialist can occupy focus position in a pseudo-cleft sentence, whereas conversely the ungrammaticality of (74b) suggests that a TP like you to see a specialist cannot. If CP can be focused in pseudo-clefts but TP cannot, then the fact that a control infinitive like PRO to see a specialist can be focused in a pseudo-cleft like (74c) suggests that it must have the same CP status as (74a) – precisely as the analysis in (74b) above claims.

Overall, the conclusion which our analysis leads us to is that infinitive complements containing the complementizer for (or its null counterpart  ) are CPs, and so are control infinitives (which contain a null complementizer ø as well as a null PRO subject).

) are CPs, and so are control infinitives (which contain a null complementizer ø as well as a null PRO subject).

|

|

|

|

للعاملين في الليل.. حيلة صحية تجنبكم خطر هذا النوع من العمل

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"ناسا" تحتفي برائد الفضاء السوفياتي يوري غاغارين

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

بمناسبة مرور 40 يومًا على رحيله الهيأة العليا لإحياء التراث تعقد ندوة ثقافية لاستذكار العلامة المحقق السيد محمد رضا الجلالي

|

|

|