Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 7-2-2022

Date: 16-2-2022

Date: 24-1-2023

|

Traditional grammars posit a category of pronoun (which we can abbreviate as PRN) to denote a class of words which are said to ‘stand in place of’ (the meaning of the prefix pro-) or ‘refer back to’ noun expressions. However, there are reasons to think that there are a number of different types of pronoun found in English and other languages (see D´echaine and Wiltschko 2002). One such type is represented by the word one in the use illustrated below:

From a grammatical perspective, one behaves like a regular count noun here in that it has the s-plural form ones and occurs in a position (after an adjective like blue/red) in which a count noun could occur. However, it is a pronoun in the sense that it has no descriptive content of its own, but rather takes its descriptive content from its antecedent (e.g. one in (26a) refers back to the noun car and so one is interpreted as meaning ‘car’). Let’s refer to this kind of pronoun as an N-pronoun (or pronominal noun).

By contrast, in the examples in (27) below, the bold-printed pronoun seems to serve as a pronominal quantifier. In the first (italicized) occurrence in each pair of examples, it is a prenominal(i.e. noun-preceding) quantifier which modifies a following noun expression(viz. guests/miners/protesters/son/cigarettes/bananas); in the second (bold-printed) occurrence it has no noun expression following it and so functions as a pronominal quantifier:

We might therefore refer to pronouns like those bold-printed in (27) as Q-pronouns (or pronominal quantifiers). If question words like which?/what? in expressions like which books?/what idea? are interrogative quantifiers, it follows that interrogative pronouns like those italicized in the examples below:

are also Q-pronouns.

A third type of pronoun are those bold-printed in the examples below:

Since the relevant words can also serve (in the italicized use) as prenominal determiners which modify a following noun, we can refer to them as D-pronouns (i.e. as pronominal determiners).

A further type of pronoun posited in traditional grammar are so-called personal pronouns like I/me/we/us/you/he/him/she/her/it/they/them. These are called personal pronouns not because they denote people (the pronoun it is not normally used to denote a person), but rather because they encode the grammatical property of person. In the relevant technical sense, I/me/my/we/us/our are said to be first-person pronouns, in that they are expressions whose reference includes the person/s speaking; you/your are second-person pronouns, in that their reference includes the addressee/s (viz. the person/s being spoken to), but excludes the speaker/s; he/him/his/she/her/it/its/they/them/their are third-person pronouns in the sense that they refer to entities other than the speaker/s and addressee/s. Personal pronouns differ morphologically from nouns and other pronouns in modern English in that they generally have (partially) distinct nominative, accusative and genitive case forms, whereas nouns have a common nominative/accusative form and a distinct genitive ’s form – as we see from the contrasts below:

Personal pronouns like he/him/his and nouns like John/John’s change their morphological form according to the position which they occupy within the sentence, so that the nominative forms he/John are required as the subject of a finite verb like snores, whereas the accusative forms him/John are required when used as the complement of a transitive verb like find (or when used as the complement of a transitive preposition), and the genitive forms his/John’s are required (inter alia) when used to express possession: these variations reflect different case forms of the relevant items.

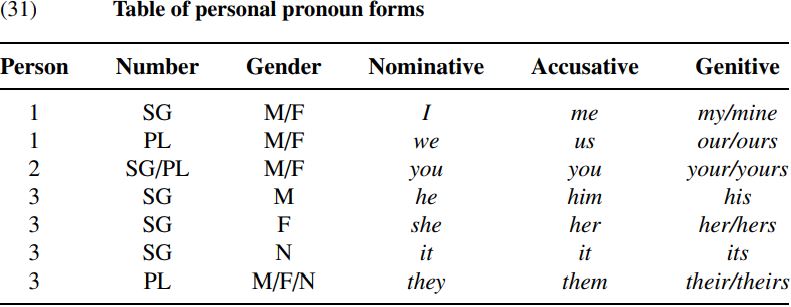

Personal pronouns are functors by virtue of lacking descriptive content: whereas a noun like dogs denotes a specific type of animal, a personal pronoun like they denotes no specific type of entity, but has to have its reference determined from the linguistic or non-linguistic context. Personal pronouns encode the grammatical properties of (first, second or third) person, (singular or plural) number, (masculine, feminine or neuter/inanimate) gender and (nominative, accusative or genitive) case, as shown in the table in (31) below:

(SG = singular; PL = plural; M = masculine; F = feminine; N = neuter. Note that some genitive pronouns have separate weak and strong forms, the weak form being used prenominally to modify a following noun expression – as in ‘Take my car’ – and the strong form being used pronominally – as in ‘Take mine’.) On the nature of gender features in English, see Namai (2000).

But what grammatical category do personal pronouns belong to? Studies by Postal (1966), Abney (1987), Longobardi (1994) and Lyons (1999) suggest that they are D-pronouns. This assumption would provide us with a unitary analysis of the syntax of the bold-printed items in the bracketed expressions in sentences such as (32a,b) below:

Since we and you in (32a) modify the nouns republicans/democrats and since determiners like the are typically used to modify nouns, it seems reasonable to suppose that we/you function as prenominal determiners in (32a). But if this is so, it is plausible to suppose that we and you also have the categorial status of determiners (i.e. D-pronouns) in sentences like (32b).

It would then follow that we/you have the categorial status of determiners in both (32a) and (32b), but differ in that they are used prenominally (i.e. with a following noun expression) in (32a), but pronominally (i.e. without any following noun expression) in (32b). Note, however, that third-person pronouns like he/she/it/they are typically used only pronominally – hence the ungrammaticality of expressions such as ∗they boys in standard varieties of English (though this is grammatical in some non-standard varieties of English – e.g. that spoken in Bristol in South-West England). Whether or not such items are used prenominally, pronominally or in both ways is a lexical property of particular items (i.e. an idiosyncratic property of individual words).

Although the D-pronoun analysis has become the ‘standard’ analysis of personal pronouns over the past three decades, it is not entirely without posing problems. For example, a typical D-pronoun like these/those can be premodified by the universal quantifier all, but a personal pronoun like they cannot:

Such a contrast is unexpected if personal pronouns like they are D-pronouns like those/these, and clearly raises questions about the true status of personal pronouns (an issue which we leave open here).

Because a number of aspects of the syntax of pronouns remain to be clarified and because the category pronoun is familiar from centuries of grammatical tradition, the label PRN/pronoun will be used throughout the rest of these topics to designate pronouns. It should, however, be borne in mind that there are a number of different types of pronoun (including N-pronouns, Qpronouns and D-pronouns), so that the term pronoun does not designate a unitary category. Some linguists prefer the alternative term proform (so that, for example, when used pronominally, one could be described as an N-proform or pro-N).

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ينظم دورة عن آليات عمل الفهارس الفنية للموسوعات والكتب لملاكاته

|

|

|