Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 25-7-2022

Date: 2024-01-04

Date: 2023-09-18

|

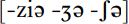

The fricatives  are made with a constriction that is further back than [s z]. Their place of articulation is variously described as palatoalveolar or postalveolar. The tongue has a wider channel than for [s z], and it is convex behind the groove, rather than concave as for [s z]. Like [s z],

are made with a constriction that is further back than [s z]. Their place of articulation is variously described as palatoalveolar or postalveolar. The tongue has a wider channel than for [s z], and it is convex behind the groove, rather than concave as for [s z]. Like [s z],  can be produced with the tongue tip either up or down.

can be produced with the tongue tip either up or down.

[ʃ] is usually accompanied in English by a secondary articulation of labialization (lip-rounding). If you compare the words ‘lease’ – ‘leash’, and ‘said’ – ‘shed’, you will probably notice quite different lip postures. For the alveolar sounds, the lips have the same shape as for the vowel; but for the postalveolars, the lips are rounded, even though the vowels are not. So a narrower transcription would be  . One possible reason for this secondary articulation is that the postalveolars have friction at a lower frequency than the alveolars. If the lips are rounded, then the friction sounds as though it has a lower pitch. Try this for yourself: isolate the

. One possible reason for this secondary articulation is that the postalveolars have friction at a lower frequency than the alveolars. If the lips are rounded, then the friction sounds as though it has a lower pitch. Try this for yourself: isolate the  sound of ‘shed’ and then unround and round the lips so you can hear the acoustic effect.

sound of ‘shed’ and then unround and round the lips so you can hear the acoustic effect.

Figure 8.9 shows a spectrogram of an Australian male speaker saying the words ‘sigh’ and ‘shy’. Note that the centre of the energy in the fricative portion is lower for [ʃ] than for [s], having significant energy at 2000 Hz and above. Lip-rounding for [ʃ] can be thought of as enhancing one of the acoustic differences between [s] and [ʃ].

Not all [ʃ] sounds in English are rounded. This reflects one source of the sound [ʃ] historically, which is a combination of [s]+[i] or [j]. Many words across varieties of English can vary between the alveolar +palatal sequence and the postalveolar sound: ‘tissue’,  , illustrates this. In some words one or the other possibility has become lexicalized, that is, it has become the normative pronunciation of the word: examples include ‘sugar’, where modern English has [ʃ], but the spelling indicates that it was originally [sj-], and ‘suit’, which is usually [su:t], can be [sju:t] but cannot be [ʃu:t].

, illustrates this. In some words one or the other possibility has become lexicalized, that is, it has become the normative pronunciation of the word: examples include ‘sugar’, where modern English has [ʃ], but the spelling indicates that it was originally [sj-], and ‘suit’, which is usually [su:t], can be [sju:t] but cannot be [ʃu:t].

In the words with the alveolar+ palatal sequence, the rounding does not start till the frication ends. In words like ‘tissue’, the rounding can start later during the fricative, so that the last syllable of ‘tissue’ is not homophonous with the word ‘shoe’. For some speakers, there are the odd pairs like ‘fisher’  and ‘fissure’

and ‘fissure’  , where in the first case there is rounding throughout the friction and in the second syllable ([ɵ] stands for a rounded version of [ə]), while in ‘fissure’ the friction is slightly longer than in ‘fisher’ and has a palatal off-glide and lip-rounding with a later onset. These are small, subtle details which not all speakers of English have in their speech.

, where in the first case there is rounding throughout the friction and in the second syllable ([ɵ] stands for a rounded version of [ə]), while in ‘fissure’ the friction is slightly longer than in ‘fisher’ and has a palatal off-glide and lip-rounding with a later onset. These are small, subtle details which not all speakers of English have in their speech.

Another place where there is some subtlety about the lip-rounding is across words, in phrases where in between [s] and [j] there is a word boundary, as in ‘I miss you’. Here, a wide range of possibilities occurs, from [s j] through to articulations that are more like [ʃ] throughout.

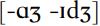

The fricative  in many instances derives historically from [z]+[i], which makes it somewhat parallel to [ʃ] (which has other sources as well). It has a much more restricted distribution than [ʃ], however: the main difference is that

in many instances derives historically from [z]+[i], which makes it somewhat parallel to [ʃ] (which has other sources as well). It has a much more restricted distribution than [ʃ], however: the main difference is that  cannot be word initial or word final in native English words.

cannot be word initial or word final in native English words.  often alternates with [ʃ] and/or [zi]: ‘Parisian’

often alternates with [ʃ] and/or [zi]: ‘Parisian’  , ‘nausea’, ‘anaesthesia’,

, ‘nausea’, ‘anaesthesia’,  ; also with

; also with  in some loanwords like ‘garage’, whose last syllable can be

in some loanwords like ‘garage’, whose last syllable can be  ). The other main source of

). The other main source of  is indeed loanwords, such as ‘negligée’, ‘beige’, ‘rouge’. It does not occur, however, at the boundary of morphemes where the rightmost morpheme is <-er>: words like ‘rosy’, ‘cosy’, ‘cheesy’ have comparative forms with [-zi-], and not

is indeed loanwords, such as ‘negligée’, ‘beige’, ‘rouge’. It does not occur, however, at the boundary of morphemes where the rightmost morpheme is <-er>: words like ‘rosy’, ‘cosy’, ‘cheesy’ have comparative forms with [-zi-], and not  (so, e.g.,

(so, e.g.,  , not

, not  ).

).

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ينظم دورة عن آليات عمل الفهارس الفنية للموسوعات والكتب لملاكاته

|

|

|