Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 4-5-2022

Date: 13-5-2022

Date: 21-5-2022

|

Presuppositions

We have, in fact, already met the most frequent kind of presupposition in English, namely, that achieved through definite noun phrases (NPs) like the book or Michael. The primary idea is that such referring expressions invite participant(s) to identify a particular referent from a specific context which is assumed to be shared by the interlocutors, but that idea could not work if those referents were not assumed to exist. Presuppositions are assumptions that are typically taken for granted in a conversation – they are often part of the common ground – and are conventionally associated with particular linguistic expressions. The term presupposition should not be confused with its everyday usage, where it is taken as near enough synonymous with the term assumption, meaning that something is taken as being true without any explicit evidence, as illustrated by [3.7]:

This is not to say that the everyday notion of assumptions is not within the scope of pragmatics; we dealt with. However, the technical usage of the term presupposition is more restricted. For example, Levinson (1983: 168) writes that it pertains to “certain pragmatic inferences or assumptions that seem at least to be built into linguistic expressions and which can be isolated using specific linguistic tests”. We will examine both those linguistic expressions and some of those tests.

Much of the literature on presuppositions has been written by language philosophers (e.g. Gottlob Frege, Peter Strawson) or semanticists (e.g. Lauri Karttunen, Paul and Carol Kiparsky) (see the references in Beaver 1997). As much of this literature is populated by analyses of decontextualised constructed sentences, often sentences that people are never likely to use, it would not seem promising for a fruitful discussion of the distinctive or variational pragmatic characteristics of the English language. However, there are two areas that can be usefully explored: (1) the particular array of linguistic forms used in English for presuppositions; and (2) the particular contexts in which presuppositions appear, along with presuppositional functions in those contexts.

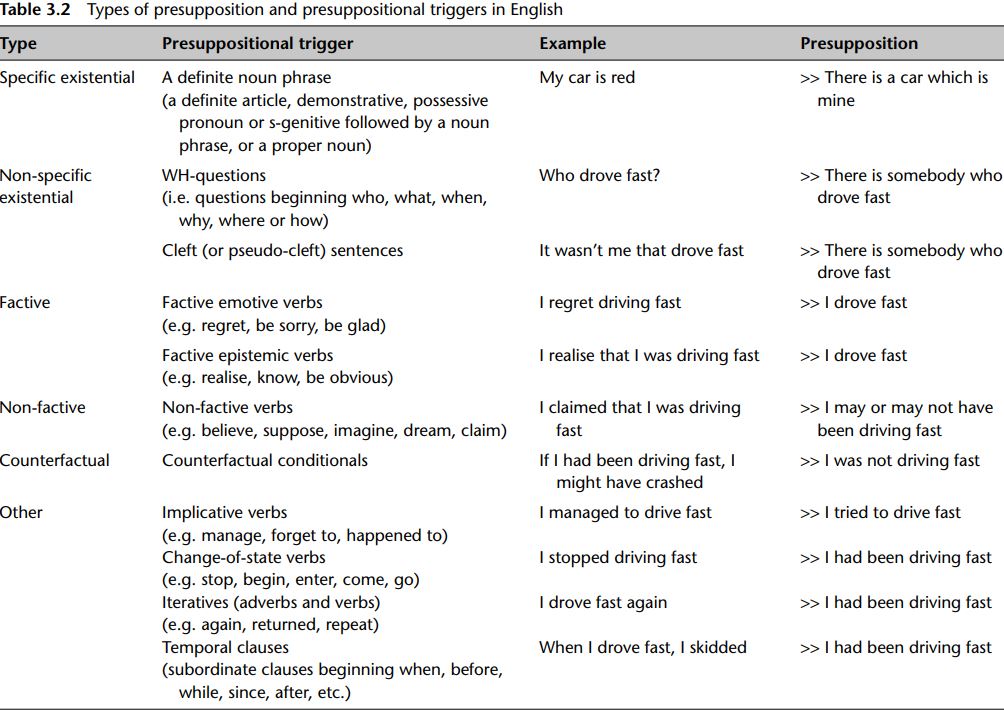

The kind of presupposition exemplified by the book and Michael in the first sentence of this section is an existential presupposition. These arise when the speaker seems to assume, and invites the hearer to assume, the existence of the entity to which they refer. Such presuppositions are discussed in early work by, for example, Frege (e.g. 1892), Russell (1905) and thoroughly by Strawson (1950). The classic, and somewhat bizarre, example Russell, Strawson and many others discuss is: The king of France is bald.

They were fascinated by the fact that the sentence is not simply true or false according to the baldness of the king. The additional issue is that it presupposes the existence of a king of France, which we know not to be the case in this modern age. Later scholars broadened the notion to include other kinds of presupposition. Consider this example: We are glad to have written this topic. Being glad about something presupposes that that something truly happened (i.e. it is true that we wrote this). This is a factive presupposition. The classic work on factivity, Kiparsky and Kiparsky (1970), discusses verbs (e.g. regret, know, realize) that presuppose the truth of their complements (the complement of our example being: to have written this topic). Some verbs, such as believe, suppose, intend and claim, seem to push the truth status of their complements into a twilight zone where we are not sure about whether they are true or not. Hence, we believe we have written this topic leaves the truth of whether we wrote it lingering in the air. These verbs trigger non-factive presuppositions. Some other structures do the opposite of factive presuppositions, that is, they presuppose that some proposition is not true. An example might be If the computer had crashed, we might have lost our book manuscript. Fortunately, this sentence does not report a calamity, because the presupposition triggered by the conditional structure suggests that the state of affairs in the first clause is not true – this is a counterfactive presupposition. With all these types of presupposition the presupposition is conventionally associated with particular linguistic forms – a definite noun phrase (the book), a particular emotive verb expression (are glad) and so on. Such linguistic forms are called presuppositional triggers. They invite a pragmatic inference to be made; that is, they invite the hearer to supply the assumptions associated with the linguistic form in its context of use.

Table 3.2 summarizes the types of presupposition and presuppositional triggers that are generally discussed in the literature (see, in particular, Levinson 1983: 181–184, also Beaver 1997: 943–944). It should not be taken as a complete list, not least because there is disagreement in the literature about types of presupposition, presuppositional triggers and whether particular items are presuppositions at all. It is also worth noting, especially with regard to the items listed under “other”, that there is some leakage into the category of conventional implicatures (see Karttunen and Peters 1979), which will be discussed briefly.

|

|

|

|

للعاملين في الليل.. حيلة صحية تجنبكم خطر هذا النوع من العمل

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"ناسا" تحتفي برائد الفضاء السوفياتي يوري غاغارين

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي يقيم ورشة تطويرية ودورة قرآنية في النجف والديوانية

|

|

|