Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-03-30

Date: 2024-03-27

Date: 2024-03-02

|

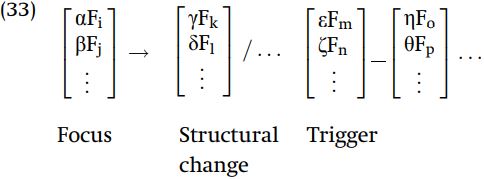

Many aspects of rule theory were introduced in our informal approach to rule writing , and they carry over in obvious ways to the formal theory that uses features. The general form of a phonological rule is:

where Fi, Fj, Fk ... are features and α, β, γ ... are plus or minus values. The arrow means “becomes,” slash means “when it is in the context,” and the dash refers to the position of the focus in that context. The matrix to the left of the arrow is the segment changed by the rule; that segment is referred to as the focus or target of the rule. The matrix immediately to the right of the arrow is the structural change, and describes the way in which the target segment is changed. The remainder of the rule constitutes the trigger (also known as the determinant or environment), stating the conditions outside the target segment which are necessary for application of the rule. Instead of the slash, a rule can be formulated with the mirror-image symbol “%,” which means “before or after,” thus “X ! Y% __Z” means “X becomes Y before or after Z.”

Each element is given as a matrix, which expresses a conjunction of features. The matrices of the target and trigger mean “all segments of the language which have the features [αFi] as well as [βFj]...” The matrix of the structural change means that when a target segment undergoes a rule, it receives whatever feature values are specified in that matrix.

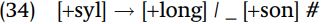

There are a few special symbols which enter into rule formulation. One which we have encountered is the word boundary, symbolized as “#.” A rule which lengthens a vowel before a word-final sonorant would be written as follows:

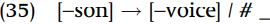

A rule which devoices a word-initial consonant would be written as:

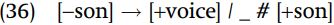

A word boundary can come between the target and the trigger segments, in which case it means “when the trigger segment is in the next word.” Such processes are relatively infrequent, but, for example, there is a rule in Sanskrit which voices a consonant at the end of a word when it is followed by a sonorant in the next word, so /tat#aham/ becomes [tad#aham] ‘that I’; voicing does not take place strictly within the word, and thus /pata:mi/ ‘I fly’ does not undergo voicing. This rule is formulated as in (36).

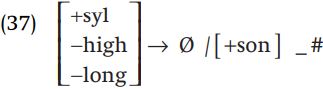

Another symbol is the null, Ø, used in the focus or structural change of a rule. As the focus, it means that the segment described to the right of the arrow is inserted in the stated context; and as the structural change, it means that the specified segment is deleted. Thus a rule that deletes a word-final short high vowel which is preceded by a sonorant would be written as follows:

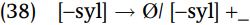

There are occasions where it is necessary to restrict a rule to apply only when a sequence occurs in different morphemes, but not within a morpheme. Suppose you find a rule that deletes a consonant after a consonant, but only when the consonants are in separate morphemes: thus the bimorphemic word /tap-ta/ with /p/ at the end of one morpheme and /t/ at the beginning of another becomes [tapa], but the monomorphemic word /tapta/ does not undergo deletion. Analogous to the word boundary, there is also a morpheme boundary symbolized by “+,” which can be used in writing rules. Thus the rule deleting the second of two consonants just in case the consonants are in different morphemes (hence a morpheme boundary comes between the consonants) is stated as:

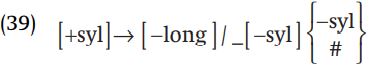

You may encounter other conventions of formalism. One such notation is the brace notation. Whereas the standard matrix [...] refers to a conjunction of properties – segments which are A and B and C all at once – braces {...} express disjunctions, that is, segments which are A or B or C. One of the most frequent uses of braces is exemplified by a rule found in a number of languages which shortens a long vowel if it is followed by either two consonants or else one consonant plus a word boundary, i.e. followed by a consonant that is followed by a consonant or #. Such a rule can be written as (39).

Most such rules use the notation to encode syllable-related properties, so in this case the generalization can be restated as “shorten a long vowel followed by a syllable-final consonant.” Using [.] as the symbol for a syllable boundary, this rule could then be reformulated as:

Although the brace notation has been a part of phonological theory, it has been viewed with considerable skepticism, partly because it is not well motivated for more than a handful of phenomena that may have better explanations (e.g. the syllable), and partly because it is a powerful device that undermines the central claim that rules operate in terms of natural classes (conjunctions of properties).

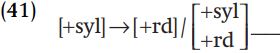

Some rules need to refer to a variably sized sequence of elements. A typical example is vowel harmony, where one vowel assimilates a feature from another vowel, and ignores any consonants that come between. Suppose we have a rule where a vowel becomes round after a round vowel, ignoring any consonants. We could not just write the rule as (41), since that incorrectly states that only vowels strictly next to round vowels harmonize.

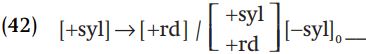

We can use the subscript-zero notation, and formalize the rule as in (42).

The expression “[-syl]0” means “any number of [-syl] segments,” from none to an infinite sequence of them.

A related notation is the parenthesis, which surrounds elements that may be present, but are not required. A rule of the form X ! Y / _ (WZ)Q means that X becomes Y before Q or before WZQ, that is, before Q ignoring WZ. The parenthesis notation essentially serves to group elements together. This notation is used most often for certain kinds of stress-assignment rules, and advancements in the theory of stress have rendered parenthesis unnecessary in many cases.

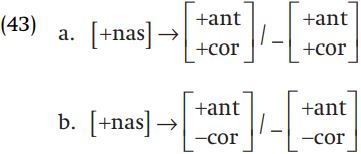

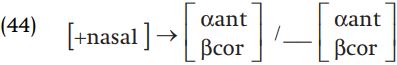

One other very useful bit of notation is the feature variable notation. So far, it has actually been impossible to formalize one of the most common phonological rules in languages, the rule which assimilates a nasal in place of articulation to the following consonant, where /mk/ ! [ŋk], /np/ ! [mp] and so on. While we can write a rule which makes any nasal become [+ant, +cor] before a [+ant, +cor] consonant – any nasal becomes [n] before /t/ – and we can write a rule to make any nasal [+ant, -cor] before a [+ant, -cor] consonant – nasals become [m] before [p] – we cannot express both changes in one rule.

The structural change cannot be “![+cor]” because when a nasal becomes [m] it becomes [-cor]. For the same reason the change cannot be “ ! [-cor]” since making a nasal become [n] makes it become [+cor]. One solution is the introduction of feature variables, notated with Greek letters α, β, γ, etc. whose meaning is “the same value.” Thus a rule which makes a nasal take on whatever values the following consonant has for place of articulation would be written as follows:

Thus when the following consonant has the value [+cor] the nasal becomes [+cor] and when the following consonant has the value [-cor] the nasal becomes [-cor]. We will return to issues surrounding this notation.

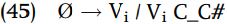

There are a couple of commonly used informal shorthand practices which you need to recognize. Many rules refer to “consonants” versus “vowels,” meaning [-syllabic] and [+syllabic] segments, and the shorthand “C” and “V” are often used in place of [-syllabic] and [+syllabic]. Also, related to the feature variable notation, it is sometimes necessary to write rules which refer to the entire set of features. A typical example would be in a rule “insert a vowel which is a copy of the preceding vowel into a word-final cluster.” Rather than explicitly listing every feature with an associated variable, such a rule might be written as:

meaning “insert a copy of the preceding vowel.”

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

معهد الكفيل للنطق والتأهيل: أطلقنا برامج متنوعة لدعم الأطفال وتعزيز مهاراتهم التعليمية والاجتماعية

|

|

|