Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 4-5-2022

Date: 1-6-2022

Date: 27-5-2022

|

Sender’s meaning3 is the meaning that the speaker or writer intends to convey by means of an utterance. Sender’s meaning is something that addressees are continually having to make informed guesses about. Addressees can give indications, in their own next utterances, of their interpretation (or by performing other actions, like Harry Potter extending his right arm between the two utterances in Example (1.1)). The sender or fellow addressees or even bystanders will sometimes offer confirmation, corrections or elaborations, along the lines of “Yes, that’s part of what I meant, but I’m also trying to tell you …” or “You’ve misunderstood me” or “The real point of what she said was …” or “Yes, and from that we can tell that he wanted you to know that …” or “The way I understand the last sentence in this paragraph is different”. Sender’s meanings, then, are the communicative goals of senders and the interpretational targets for addressees. They are rather private, however. Senders will sometimes not admit that they intended to convey selfish or hurtful implicatures and, at times, may be unable to put across the intention behind an utterance of theirs any better than they have already done by producing the utterance.

Sender’s thoughts are private, but utterances are publicly observable. Typed or written utterances can be studied on paper or on the screens of digital devices. Spoken utterances can be recorded and played back. Other people who were present when an utterance was produced can be asked what they heard, or saw being written. We cannot be sure that sender meaning always coincides with addressee interpretation, so there is a dilemma over what to regard as the meaning of an utterance. Is it sender’s meaning or the interpretation that is made from the utterance, in context, by the addressee(s)? We cannot know exactly what either of these is. However, as language users, we gain experience as both senders and addressees and develop intuitions about the meaning an utterance is likely to carry in a given context. So utterance meaning is a necessary fiction that linguists doing semantics and pragmatics have to work with. It is the meaning – explicature and implicatures – that an utterance would likely be understood as conveying when interpreted by people who know the language, are aware of the context, and have whatever background knowledge the sender could reasonably presume to be available to the addressee(s).

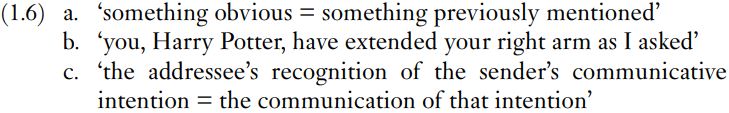

Utterances are the data for linguistics, so linguists interested in meaning want to explain utterance meaning. But, because utterances are instances of sentences in use, an important first step is an account of the meanings of sentences. I will take sentence meaning to be the same as literal meaning (already introduced in Section 1.1.2: the meanings that people familiar with the language can agree on for sentences considered in isolation). As an illustration of how utterance meaning relates to sentence meaning, consider the sentence That’s it, the basis for part of (1.1). I hope you agreed that, when context is ignored, the sentence has the meaning shown in (1.6a), but that, after learning that it was used for an utterance by Mr Ollivander while measuring up Harry Potter for a wand, you agreed that its explicature (the basic utterance meaning) could reasonably be represented as in (1.6b).

When I was discussing Table 1.1 – in the paragraph that also introduced the terms addressee and sender – I used the same sentence as the basis for an utterance “that’s it” in the text. That utterance – also based on the sentence meaning represented in (1.6a) – had as its explicature (1.6c), considerably different from (1.6b). (What could the implicatures have been? Mr O. was probably conveying ‘stop moving now’, Harry by then having moved his arm out to the desired angle, and he was giving Harry a nod of approval, somewhat like calling him “a good boy”. With my utterance, I wanted you to see that the addressee’s recognition of the sender’s intention brings sudden closure to what otherwise looks like a complicated process.)

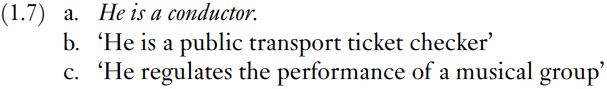

Ordinary language users have readily accessible intuitions about sentences. Among other items of information that people proficient in English can easily come to realize on the basis of their knowledge of the language is that the sentence in example (1.7a) has two meanings (it is ambiguous), shown in (1.7b) and (1.7c).

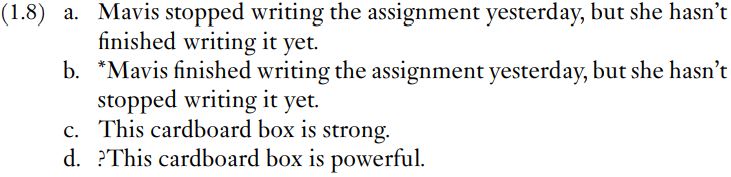

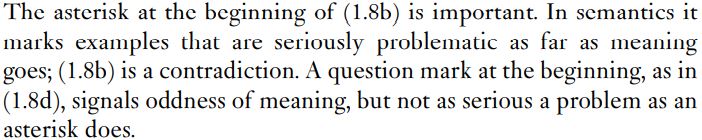

Ordinary language users’ access to the meanings of words is less direct. The meaning of a word is the contribution it makes to the meanings of sentences in which it appears. Of course people know the meanings of words in their language in the sense that they know how to use the words, but this knowledge is not immediately available in the form of reliable intuitions. Ask non-linguists whether strong means the same as powerful or whether finish means the same as stop and they might well say Yes. They would be at least partly wrong. To have a proper feeling for what these words mean, it is best to consider sentences containing them, as in (1.8a–d). (All four are sentences, so there is no need to distinguish them from utterances or meanings, which is why I have not put them in italics.)

Examples (1.8a, b) are evidence that finishing is a special kind of stopping: ‘stopping after the goal has been reached’. Examples (1.8c, d) are part of the evidence showing that strong is an ambiguous word, meaning either ‘durable’ or ‘powerful’. Only one of the two meanings is applicable to cardboard boxes.

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

في مستشفى الكفيل.. نجاح عملية رفع الانزلاقات الغضروفية لمريض أربعيني

|

|

|