تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 19-2-2017

Date: 25-2-2017

Date: 25-2-2017

|

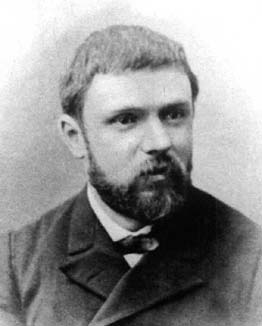

Died: 17 July 1912 in Paris, France

Henri Poincaré's father was Léon Poincaré and his mother was Eugénie Launois. They were 26 and 24 years of age, respectively, at the time of Henri's birth. Henri was born in Nancy where his father was Professor of Medicine at the University. Léon Poincaré's family produced other men of great distinction during Henri's lifetime. Raymond Poincaré, who was prime minister of France several times and president of the French Republic during World War I, was the elder son of Léon Poincaré's brother Antoine Poincaré. The second of Antoine Poincaré's sons, Lucien Poincaré, achieved high rank in university administration.

Henri was [2]:-

... ambidextrous and was nearsighted; during his childhood he had poor muscular coordination and was seriously ill for a time with diphtheria. He received special instruction from his gifted mother and excelled in written composition while still in elementary school.

In 1862 Henri entered the Lycée in Nancy (now renamed the Lycée Henri Poincaré in his honour). He spent eleven years at the Lycée and during this time he proved to be one of the top students in every topic he studied. Henri was described by his mathematics teacher as a "monster of mathematics" and he won first prizes in the concours général, a competition between the top pupils from all the Lycées across France.

Poincaré entered the École Polytechnique in 1873, graduating in 1875. He was well ahead of all the other students in mathematics but, perhaps not surprisingly given his poor coordination, performed no better than average in physical exercise and in art. Music was another of his interests but, although he enjoyed listening to it, his attempts to learn the piano while he was at the École Polytechnique were not successful. Poincaré read widely, beginning with popular science writings and progressing to more advanced texts. His memory was remarkable and he retained much from all the texts he read but not in the manner of learning by rote, rather by linking the ideas he was assimilating particularly in a visual way. His ability to visualise what he heard proved particularly useful when he attended lectures since his eyesight was so poor that he could not see the symbols properly that his lecturers were writing on the blackboard.

After graduating from the École Polytechnique, Poincaré continued his studies at the École des Mines. His [21]:-

... meticulous notes taken on field trips while a student there exhibit a deep knowledge of the scientific and commercial methods of the mining industry; a subject that interested him throughout his life.

After completing his studies at the École des Mines Poincaré spent a short while as a mining engineer at Vesoul while completing his doctoral work. As a student of Charles Hermite, Poincaré received his doctorate in mathematics from the University of Paris in 1879. His thesis was on differential equations and the examiners were somewhat critical of the work. They praised the results near the beginning of the work but then reported that the (see for example [21]):-

... remainder of the thesis is a little confused and shows that the author was still unable to express his ideas in a clear and simple manner. Nevertheless, considering the great difficulty of the subject and the talent demonstrated, the faculty recommends that M Poincaré be granted the degree of Doctor with all privileges.

Immediately after receiving his doctorate, Poincaré was appointed to teach mathematical analysis at the University of Caen. Reports of his teaching at Caen were not wholly complimentary, referring to his sometimes disorganised lecturing style. He was to remain there for only two years before being appointed to a chair in the Faculty of Science in Paris in 1881. In 1886 Poincaré was nominated for the chair of mathematical physics and probability at the Sorbonne. The intervention and the support of Hermite was to ensure that Poincaré was appointed to the chair and he also was appointed to a chair at the École Polytechnique. In his lecture courses to students in Paris [2]:-

... changing his lectures every year, he would review optics, electricity, the equilibrium of fluid masses, the mathematics of electricity, astronomy, thermodynamics, light, and probability.

Poincaré held these chairs in Paris until his death at the early age of 58.

Before looking briefly at the many contributions that Poincaré made to mathematics and to other sciences, we should say a little about his way of thinking and working. He is considered as one of the great geniuses of all time and there are two very significant sources which study his thought processes. One is a lecture which Poincaré gave to l'Institute Général Psychologique in Paris in 1908 entitled Mathematical invention in which he looked at his own thought processes which led to his major mathematical discoveries. The other is the book [30] by Toulouse who was the director of the Psychology Laboratory of l'École des Hautes Études in Paris. Although published in 1910 the book recounts conversations with Poincaré and tests on him which Toulouse carried out in 1897.

In [30] Toulouse explains that Poincaré kept very precise working hours. He undertook mathematical research for four hours a day, between 10 am and noon then again from 5 pm to 7 pm. He would read articles in journals later in the evening. An interesting aspect of Poincaré's work is that he tended to develop his results from first principles. For many mathematicians there is a building process with more and more being built on top of the previous work. This was not the way that Poincaré worked and not only his research, but also his lectures and books, were all developed carefully from basics. Perhaps most remarkable of all is the description by Toulouse in [30] of how Poincaré went about writing a paper. Poincaré:-

... does not make an overall plan when he writes a paper. He will normally start without knowing where it will end. ... Starting is usually easy. Then the work seems to lead him on without him making a wilful effort. At that stage it is difficult to distract him. When he searches, he often writes a formula automatically to awaken some association of ideas. If beginning is painful, Poincaré does not persist but abandons the work.

Toulouse then goes on to describe how Poincaré expected the crucial ideas to come to him when he stopped concentrating on the problem:-

Poincaré proceeds by sudden blows, taking up and abandoning a subject. During intervals he assumes ... that his unconscious continues the work of reflection. Stopping the work is difficult if there is not a sufficiently strong distraction, especially when he judges that it is not complete ... For this reason Poincaré never does any important work in the evening in order not to trouble his sleep.

As Miller notes in [21]:-

Incredibly, he could work through page after page of detailed calculations, be it of the most abstract mathematical sort or pure number calculations, as he often did in physics, hardly ever crossing anything out.

Let us examine some of the discoveries that Poincaré made with this method of working. Poincaré was a scientist preoccupied by many aspects of mathematics, physics and philosophy, and he is often described as the last universalist in mathematics. He made contributions to numerous branches of mathematics, celestial mechanics, fluid mechanics, the special theory of relativity and the philosophy of science. Much of his research involved interactions between different mathematical topics and his broad understanding of the whole spectrum of knowledge allowed him to attack problems from many different angles.

Before the age of 30 he developed the concept of automorphic functions which are functions of one complex variable invariant under a group of transformations characterised algebraically by ratios of linear terms. The idea was to come in an indirect way from the work of his doctoral thesis on differential equations. His results applied only to restricted classes of functions and Poincaré wanted to generalise these results but, as a route towards this, he looked for a class functions where solutions did not exist. This led him to functions he named Fuchsian functions after Lazarus Fuchs but were later named automorphic functions. The crucial idea came to him as he was about to get onto a bus, as he relates in Science and Method (1908):-

At the moment when I put my foot on the step the idea came to me, without anything in my former thoughts seeming to have paved the way for it, that the transformation that I had used to define the Fuchsian functions were identical with those of non-euclidean geometry.

In a correspondence between Klein and Poincaré many deep ideas were exchanged and the development of the theory of automorphic functions greatly benefited. However, the two great mathematicians did not remain on good terms, Klein seeming to become upset by Poincaré's high opinions of Fuchs' work. Rowe examines this correspondence in [149].

Poincaré's Analysis situs , published in 1895, is an early systematic treatment of topology. He can be said to have been the originator of algebraic topology and, in 1901, he claimed that his researches in many different areas such as differential equations and multiple integrals had all led him to topology. For 40 years after Poincaré published the first of his six papers on algebraic topology in 1894, essentially all of the ideas and techniques in the subject were based on his work. Even today the Poincaré conjecture remains as one of the most baffling and challenging unsolved problems in algebraic topology.

Homotopy theory reduces topological questions to algebra by associating with topological spaces various groups which are algebraic invariants. Poincaré introduced the fundamental group (or first homotopy group) in his paper of 1894 to distinguish different categories of 2-dimensional surfaces. He was able to show that any 2-dimensional surface having the same fundamental group as the 2-dimensional surface of a sphere is topologically equivalent to a sphere. He conjectured that this result held for 3-dimensional manifolds and this was later extended to higher dimensions. Surprisingly proofs are known for the equivalent of Poincaré's conjecture for all dimensions strictly greater than three. No complete classification scheme for 3-manifolds is known so there is no list of possible manifolds that can be checked to verify that they all have different homotopy groups.

Poincaré is also considered the originator of the theory of analytic functions of several complex variables. He began his contributions to this topic in 1883 with a paper in which he used the Dirichlet principle to prove that a meromorphic function of two complex variables is a quotient of two entire functions. He also worked in algebraic geometry making fundamental contributions in papers written in 1910-11. He examined algebraic curves on an algebraic surface F(x, y, z) = 0 and developed methods which enabled him to give easy proofs of deep results due to Émile Picard and Severi. He gave the first correct proof of a result stated by Castelnuovo, Enriques and Severi, these authors having suggested a false method of proof.

His first major contribution to number theory was made in 1901 with work on [1]:-

... the Diophantine problem of finding the points with rational coordinates on a curve f (x, y) = 0, where the coefficients of f are rational numbers.

In applied mathematics he studied optics, electricity, telegraphy, capillarity, elasticity, thermodynamics, potential theory, quantum theory, theory of relativity and cosmology. In the field of celestial mechanics he studied the three-body-problem, and the theories of light and of electromagnetic waves. He is acknowledged as a co-discoverer, with Albert Einstein and Hendrik Lorentz, of the special theory of relativity. We should describe in a little more detail Poincaré's important work on the 3-body problem.

Oscar II, King of Sweden and Norway, initiated a mathematical competition in 1887 to celebrate his sixtieth birthday in 1889. Poincaré was awarded the prize for a memoir he submitted on the 3-body problem in celestial mechanics. In this memoir Poincaré gave the first description of homoclinic points, gave the first mathematical description of chaotic motion, and was the first to make major use of the idea of invariant integrals. However, when the memoir was about to be published in Acta Mathematica, Phragmen, who was editing the memoir for publication, found an error. Poincaré realised that indeed he had made an error and Mittag-Leffler made strenuous efforts to prevent the publication of the incorrect version of the memoir. Between March 1887 and July 1890 Poincaré and Mittag-Leffler exchanged fifty letters mainly relating to the Birthday Competition, the first of these by Poincaré telling Mittag-Leffler that he intended to submit an entry, and of course the later of the 50 letters discuss the problem concerning the error. It is interesting that this error is now regarded as marking the birth of chaos theory. A revised version of Poincaré's memoir appeared in 1890.

Poincaré's other major works on celestial mechanics include Les Méthodes nouvelles de la mécanique céleste in three volumes published between 1892 and 1899 and Leçons de mecanique céleste (1905). In the first of these he aimed to completely characterise all motions of mechanical systems, invoking an analogy with fluid flow. He also showed that series expansions previously used in studying the 3-body problem were convergent, but not in general uniformly convergent, so putting in doubt the stability proofs of Lagrange and Laplace.

He also wrote many popular scientific articles at a time when science was not a popular topic with the general public in France. As Whitrow writes in [2]:-

After Poincaré achieved prominence as a mathematician, he turned his superb literary gifts to the challenge of describing for the general public the meaning and importance of science and mathematics.

Poincaré's popular works include Science and Hypothesis (1901), The Value of Science (1905), and Science and Method (1908). A quote from these writings is particularly relevant to this archive on the history of mathematics. In 1908 he wrote:-

The true method of foreseeing the future of mathematics is to study its history and its actual state.

Finally we look at Poincaré's contributions to the philosophy of mathematics and science. The first point to make is the way that Poincaré saw logic and intuition as playing a part in mathematical discovery. He wrote in Mathematical definitions in education (1904):-

It is by logic we prove, it is by intuition that we invent.

In a later article Poincaré emphasised the point again in the following way:-

Logic, therefore, remains barren unless fertilised by intuition.

McLarty [119] gives examples to show that Poincaré did not take the trouble to be rigorous. The success of his approach to mathematics lay in his passionate intuition. However intuition for Poincaré was not something he used when he could not find a logical proof. Rather he believed that formal arguments may reveal the mistakes of intuition and logical argument is the only means to confirm insights. Poincaré believed that formal proof alone cannot lead to knowledge. This will only follow from mathematical reasoning containing content and not just formal argument.

It is reasonable to ask what Poincaré meant by "intuition". This is not straightforward, since he saw it as something rather different in his work in physics to his work in mathematics. In physics he saw intuition as encapsulating mathematically what his senses told him of the world. But to explain what "intuition" was in mathematics, Poincaré fell back on saying it was the part which did not follow by logic:-

... to make geometry ... something other than pure logic is necessary. To describe this "something" we have no word other than intuition.

The same point is made again by Poincaré when he wrote a review of Hilbert's Foundations of geometry (1902):-

The logical point of view alone appears to interest [Hilbert]. Being given a sequence of propositions, he finds that all follow logically from the first. With the foundations of this first proposition, with its psychological origin, he does not concern himself.

We should not give the impression that the review was negative, however, for Poincaré was very positive about this work by Hilbert. In [181] Stump explores the meaning of intuition for Poincaré and the difference between its mathematically acceptable and unacceptable forms.

Poincaré believed that one could choose either euclidean or non-euclidean geometry as the geometry of physical space. He believed that because the two geometries were topologically equivalent then one could translate properties of one to the other, so neither is correct or false. for this reason he argued that euclidean geometry would always be preferred by physicists. This, however, has not proved to be correct and experimental evidence now shows clearly that physical space is not euclidean.

Poincaré was absolutely correct, however, in his criticism that those like Russell who wished to axiomatise mathematics; they were doomed to failure. The principle of mathematical induction, claimed Poincaré, cannot be logically deduced. He also claimed that arithmetic could never be proved consistent if one defined arithmetic by a system of axioms as Hilbert had done. These claims of Poincaré were eventually shown to be correct.

We should note that, despite his great influence on the mathematics of his time, Poincaré never founded his own school since he did not have any students. Although his contemporaries used his results they seldom used his techniques.

Poincaré achieved the highest honours for his contributions of true genius. He was elected to the Académie des Sciences in 1887 and in 1906 was elected President of the Academy. The breadth of his research led to him being the only member elected to every one of the five sections of the Academy, namely the geometry, mechanics, physics, geography and navigation sections. In 1908 he was elected to the Académie Francaise and was elected director in the year of his death. He was also made chevalier of the Légion d'Honneur and was honoured by a large number of learned societies around the world. He won numerous prizes, medals and awards.

Poincaré was only 58 years of age when he died [3]:-

M Henri Poincaré, although the majority of his friends were unaware of it, recently underwent an operation in a nursing home. He seemed to have made a good recovery, and was about to drive out for the first time this morning. He died suddenly while dressing.

His funeral was attended by many important people in science and politics [3]:-

The President of the Senate and most of the members of the Ministry were present, and there were delegations from the French Academy, the Académie des Sciences, the Sorbonne, and many other public institutions. The Prince of Monaco was present, the Bey of Tunis was represented by his two sons, and Prince Roland Bonaparte attended as President of the Paris Geographical Society. The Royal Society was represented by its secretary, Sir Joseph Larmor, and by the Astronomer Royal, Mr F W Dyson.

Let us end with a quotation from an address at the funeral:-

[M Poincaré was] a mathematician, geometer, philosopher, and man of letters, who was a kind of poet of the infinite, a kind of bard of science.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتبة أمّ البنين النسويّة تصدر العدد 212 من مجلّة رياض الزهراء (عليها السلام)

|

|

|