تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 3-3-2017

Date: 22-2-2017

Date: 3-3-2017

|

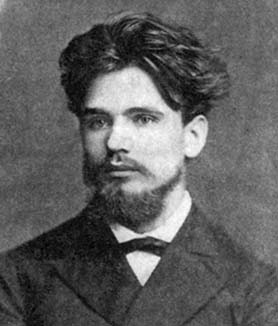

Died: 8 November 1940 in Leningrad, Russia

Andrei Petrovich Kiselev's name is sometimes transliterated as Kiselyov. His father Petr Kiselev was born around 1815 and his mother Anna N was born around 1818. It was a family of merchants who were quite poor. Andrei was the youngest of his parents' six children having older siblings Nicholas (born about 1838), Pelagia (born about 1848), Petr (born about 1848), Mari (born about 1850), and Alexandr (born about 1851). Kiselev attended the district school in Mtsensk and from there he went to the Gymnasium in Oryol, the main city in the region. There is no way that Kiselev's family could have afforded to give him this high quality school education but he was able to attend these school partly through the generosity of merchant friends who helped support him and partly through scholarships he was awarded by the schools because of his outstanding performance. It is worth recording at this point that at least two of the mathematics teachers who taught Kiselev during his school years taught from textbooks that they had written themselves. Perhaps this influenced Kiselev to become a writer of textbooks when he himself became a school teacher. He graduated from this Gymnasium in 1871 having won the gold medal and, in the same year, entered the Physics and Mathematics Faculty of St Petersburg University.

At St Petersburg University, Kiselev was taught by a number of world-class mathematicians. He attended lectures by Pafnuty Lvovich Chebyshev, Aleksandr Nikolaevich Korkin, Egor Ivanovich Zolotarev, Osip Ivanovich Somov and others. In 1874, while an undergraduate, he married Mari Edwardovna Schultz; they had three children. Their son Vladimir graduated from St Petersburg State University and then joined the Navy, their daughter Elena began training to become a mathematics teacher but was forced to give up because of illness, and their other daughter graduated from the St Petersburg Women's Medical Institute. Kiselev graduated in 1875 from the Physics and Mathematics Faculty of St Petersburg University with a degree which entitled him to teach in Gymnasia. After graduating, he taught mathematics, mechanics and drawing at the 'real school' in Voronezh which had recently opened. A real school, which followed the German model, trained people to enter technical higher education while a Gymnasium trained people to enter the university system. Despite the Gymnasium being the higher quality institution, nevertheless the real schools on the whole taught their pupils more mathematics.

Kiselev taught at the 'real school' in Voronezh until July 1891 when he spent a year teaching at a Gymnasium in Kursk before returning to Voronezh to teach at the Voronezh cadet corps. This was not the first time he had taught there for during his years teaching at the real school he had also done some part-time teaching at the cadet corps. He continued to teach at the Voronezh cadet corps until he retired in 1901. He ended up a rich man because of his textbooks which became classics and were used in Russia for a great many years. Let us now list these texts.

Here are the most important of Kiselev's textbooks: Systematic arithmetic course for secondary schools (1884); Elementary Algebra (1888); Elementary Geometry (1892-1893); Additional topics in algebra (a course of the 7th grade real schools) (1893); Quick arithmetic for urban schools (1895); A Brief algebra for girls' schools and seminaries (1896); An elementary physics for secondary schools with a number of exercises and problems (1902); Physics (two volumes) (1908); Elements of the differential and integral calculus (1908); The initial study of derivatives for the 7th grade real schools (1911); Graphical representation of some of the features discussed in elementary algebra (1911); On topics in elementary geometry, which are usually solved by means of limits (1916); Brief algebra (1917); Brief arithmetic for urban county schools (1918); Irrational numbers, considered as infinite non-periodic fractions (1923); andElements of algebra and analysis (2 volumes) (1930-1931).

It was the first three of these books which were the main school mathematics texts in Russia for many years. Many of the other books were simply adaptations of these three to different types of educational establishments. However, books on other subjects such as Physics, which went through 13 editions, andElements of the differential and integral calculus which also went through multiple editions were also popular but never came near to matching the incredible popularity of Systematic arithmetic course for secondary schools, Elementary Algebra and Elementary Geometry. The following gives a good indication of the sales of these books [7]:-

A surviving notebook of Kiselev's indicates that, for example, in 1915 alone his earnings from 'Arithmetic' and 'Algebra' were ten times greater than his annual pension (which was, it should be noted, almost a general's pension).

A review of Elementary Geometry written in 1893, the year after the book was published, states quite correctly that it was:-

... structured in accordance with the views on the exposition of this subject that have been expressed by the authors of the latest French and German handbooks, particularly the former.

This was clearly the case for, in the Preface to the first edition of this book, Kiselev quotes ten geometry courses in French and German published in the previous decade. What made these books so successful? Here is the reasons given by a Russian educator in 1941 [7]:-

Kiselev's textbooks came out on top because they were exemplars of a teacher's common sense and experience. The well-known Russian mathematics educator Ivan Andronov (1941) once wrote that Kiselev knew his strengths and did not undertake that for which his strengths might not have been sufficient. Kiselev's textbooks are well-organized and logical (later, they were found to contain not a few logical gaps, but all of these were beyond the understanding of the ordinary student). In the course in geometry - Kiselev's most popular course - practically all of the assertions are grounded and proved. But Kiselev never tried to offer a strict axiomatic course with complete indication of axioms and all of the references that a professional mathematician would have considered necessary.

There were other reasons too which were not related to the quality of the texts but rather to Kiselev's skills as a salesman. He sent free copies of his books to teachers and to the offices of journals where he hoped a review might appear. These selling techniques are common today but in Kiselev's time these were new ways of selling books and they certainly added to the success of the books. However, success ultimately depends on having outstanding books and Kiselev seems to have produced books with just the right approach. Kiselev himself suggested that the properties required of a good textbook were precision, simplicity, and conciseness.

When the Russian Revolution took place in 1917 it looked at first as if Kiselev's good life, living off a good pension and royalties, would be over. He had retired in 1901 and after a while had moved to St Petersburg to be near his publishers. However, the city was badly affected by the Revolution and the civil war that followed. With food scarce and his pension and income from books taken away, Kiselev returned to Voronezh where he took up teaching again in the colleges there. Kiselev's books became irrelevant to the Communist ideas of education in the years following the Revolution where all textbooks were considered unnecessary. However, many teachers ignored the new ideas and continued to use Kiselev's books. Slowly they returned to full use after the Moscow Mathematical Society, at a meeting held on 9 April 1937, recommended that Kiselev's Geometry should be, for the time being, the book used by schools. By the 1950s the book was still in widespread use and most Russian mathematicians who were at school in the early 1960s said that they had used Kiselev's books.

We give an idea of the style of Kiselev's Geometry by quoting from Alex Bogomolny's review of Planimetry [4]:-

The most shining example is Kiselev's treatment of the circumference and π. Circumference is defined as the limit of the perimeters of regular polygons inscribed into the circle when the number of sides is doubled indefinitely. Doesn't that sound impressive? But consider then that Kiselev precedes the definition with a reasonably developed theory of limits. The book gives a very clear introduction into the theory of limits which, although not 100% rigorous, neither noticeably cuts corners. For example, the book does prove that the limit (which is the circumference) exists. This comes after a thorough discussion of similarity. In particular, he proves that regular polygons with the same number of sides are similar, and their sides have the same ratio as their radii. Combining this with the theory of limits he derives the fact that the ratio of the circumference to the diameter is the same for all circles and thus introduces π.

Here is another example of Kiselev's style, this time from Alex Bogomolny's review of Stereometry [5]:-

On the whole, the economy of presentation is nothing short of remarkable. Just to take one example: Cavalieri's Principle. Kiselev rightly observes that to justify it one needs methods that would go beyond elementary mathematics. However, the principle is elegant and useful and mentioning it supplies an engaging historical background along with a viable demonstration of the continuity of the evolution of mathematics over time. So, based on the theory of limits developed in the first part (Planimetry), Kiselev proves (although without ever employing the symbol lim) the principle for triangular pyramids and uses the occasion to mention Hilbert's third problem. Later on, he applies the principle to determine the volume of a ball (but now without proof) and makes use of the opportunity to mention the work of Archimedes and of the recovery of his tomb by Cicero.

He was able to return to St Petersburg, by then known as Leningrad, towards the end of his life. It was around this time that Kiselev said:-

I am happy that I lived to see the days when mathematics became the property of the broad masses. Is it possible to compare the meagre circulation of pre-revolutionary times to the present. And it's not surprising. After all, the whole country is now studying. I am glad that in my old age I can be useful to their great motherland.

We should say a little about two further aspects of Kiselev's life, namely his ideas as a teacher and his involvement in politics. We know a little about his ideas on teaching through a report he wrote in 1907. We quote from [7]:-

At that time, the liberally-minded public took a decisive stand against examinations as a practice that constrained students, engendered a regime of rigid control, and so on. Kiselev spoke about the various "aberrations" in the schools: the fact that classes were overcrowded, the fact that there was not enough time properly to interview and assess all of the students in a class, the fact that school schedules were poorly designed, as a result of which there were "empty" lessons at the end of the year, which students spent playing games. He spoke about the importance of independent work and examinations as a means of instigating students to engage in such work, and he pointed out that an examination is often the teacher's only opportunity thoroughly to evaluate the students. He concluded his report, however, not by urging that examinations be preserved, but merely by recommending that no support be given to petitions for their elimination, leaving the decision to others.

Rather than give details of his political career, suffice to say that for many years he sat on the Voronezh city council. He also served on the boards of many educational institutions. In the time before the Revolution, he stood for the Russian National Duma on a fairly right-wing policy. He argued that the most pressing problem was agriculture. He did not agree with policies to take land away from the landowners but argued that peasants should be settled on unoccupied lands. He was not elected to the Russian National Duma but continued to play a big role in local Voronezh politics.

He has been honoured in a number of ways. During his lifetime Kiselev was awarded the Order of St Anne 3rd degree (1894), the Order of St Stanislaus 2nd degree (1896), the Order of St Anne 2nd degree (1899), and the Order of the Red Banner of Labour (1934). After his death more honours were given to him: in his native town of Mtsensk the Gymnasium No 3 has been named after him; also in Voronezh there is a school named after him; and the building which houses the history department of Oryol State University is named after him.

He taught several pupils who went on to have top careers as mathematicians. For example Sergei Alekseevich Chaplygin was taught in Voronezh by Kiselev. A great many others, such as Iossif Vladimirovich Ostrovskii, were turned on to mathematics by reading Kiselev's books. But perhaps the greatest compliment of all was from Vladimir Igorevich Arnold. When asked what textbook was best to use in schools, he replied, "I would go back to Kiselev".

After his death in Leningrad, Kiselev was buried in the Volkov cemetery, in an area reserved for academics. His grave is next to that of the famous chemist Dmitry Ivanovich Mendeleev who produced the periodic table.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

5 علامات تحذيرية قد تدل على "مشكل خطير" في الكبد

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

لحماية التراث الوطني.. العتبة العباسية تعلن عن ترميم أكثر من 200 وثيقة خلال عام 2024

|

|

|