Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2025-04-09

Date: 2025-04-20

Date: 2024-01-20

|

Modifiers of state verbs

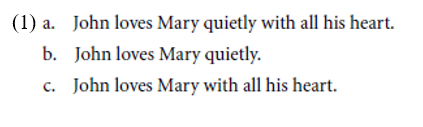

Typically, of course, modifiers of state verbs fail to evidence the Davidsonian entailment patterns. Consider, for example, (1) in which we have a doubly modified love.

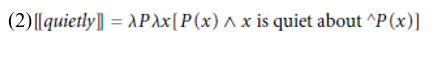

Clearly there is Drop, since (1a) entails (1b) and (1c). But since these modifiers fail to exhibit Non-Entailment – (1b) and (1c) together clearly do entail (1a) – they can be treated simply as predicate modifiers. A sketch of the interpretation of quietly is given in (2).

On such an analysis, the modifier restricts the extension of the predicate subsectively: the set of individuals who love Mary quietly is a subset of those who love Mary, as is the set of individuals who love Mary with all their heart. And the set of individuals who love Mary quietly with all their heart is simply the intersection of these two sets, as standard predicate-modificational accounts would predict (Thomason and Stalnaker 1973).

Returning to (6) in Manner adverbials, consider first the permutation facts: of the permutations given in (7) only (7a) seems perfectly natural; (7c) is quite awkward and (7b) is also somewhat degraded. Of course adverbial-ordering restrictions of this sort need not necessarily reflect any deep syntactic or semantic facts, and might reasonably be given a pragmatic or even prosodic account (Costa 1997). The more semantic Drop and Non-Entailment facts are clearly more central to the argument. It should be pointed out, incidentally, that the Drop facts are primary, since Non-Entailment without Drop doesn’t tell us much; Non- Entailment is to be expected if there is no Drop.

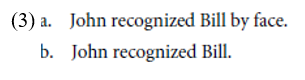

Unfortunately for Landman, the modifiers in (8) do not appear to genuinely have the Drop property. While it might be the case that (8) entails both (8a) and (8b), it is fairly clear that neither (8a) nor (8b) entails (8c). To know someone by face from television is not to know that person. It would simply be false for me to claim that I know Peter Jennings or David Letterman, although I know them both well by face from TV. If you know somebody, you typically know his or her name and some significant facts about that person. But you may know somebody by face without knowing much of anything about the person. The adverbial by face, then, appears to be a type of non-intersective modifier which has particular, lexically-specific entailments. We will have more to say about such modifiers below, suggesting that these readings are, in some sense “collocational.” Note that when the modifier by face combines with an event verb, it is droppable – the entailment from (3a) to (3b) certainly goes through.

This indicates that there is a qualitative semantic difference between state verb modification and event verb modification, even for modifiers such as by face that appear with both types of predicates.

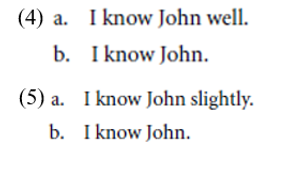

In contrast to by face, the modifiers well and from a party do seem be droppable. The fact that it is possible to drop well in (4) but not slightly in (5) shows us that the droppability is tied to the lexical semantics of this adverb.

It certainly doesn’t indicate that well is associated with an event predicate but slightly is not.1 As we shall see shortly, standard treatments of degree adverbial modification, which do not involve Davidsonian predication, make exactly the right predictions for (4) and (5).

Although the modifier from television is clearly droppable, the precise semantics of these adverbs makes it quite dubious that it is an event predicate. Such from-modifiers have a fairly broad distribution, appearing not only with verbs but also with nouns:

(6)

a. I remember you from our art class.

b. My coat smells very smoky from the barbecue last night.

c. I recognized you from the way you walk.

d. John owes Bill money from the last time they were out.

e. We have free tickets from when the game was rained out.

f. We just got our prize from when we won the competition.

(7)

a. The debris from when the bomb exploded is still being picked up.

b. I tripped over one of the bottles from last night on the way to the john.

In all cases, the from-modifier appears to have a general explanatory character. Thus (6a) seems to mean something like that our being at a dance class is causally related to the fact that I remember you. Like other causal clauses, from-modifiers are factive, and thus droppable (Kiparsky and Kiparsky 1971).2 Whether the causal relation is an event relation is, of course, the subject of hot debate (see, for example, Peterson (1997). There is much evidence that at least because-clauses relate propositional meanings, not event descriptions (Johnston 1994).

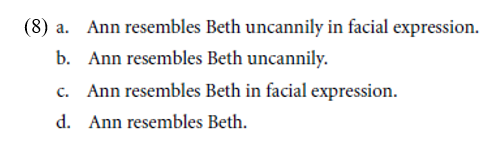

It is not at all clear, then, that indeed provides evidence for the Davidsonian account of the verb know. Equally dubious are a number of similar cases in which modifiers of state verbs appear to evidence Davidsonian-like entailment patterns. Mittwoch (2005), for example, suggests that (8a) entails (8b) and (8c), but that (8b) and (8c) taken together do not entail (8a).

While it is certainly true that (8b) and (8c) taken together do not entail (8a) and it might appear that (8a) would entail (8b–d), closer inspection calls this latter fact into question. If the only thing that Ann and Beth have in common is their facial expression – say Ann is tall, Beth short; Ann blonde, and Beth brunette – we would typically take (8a) to be true, but would certainly say that (8b) and (8d) are false.

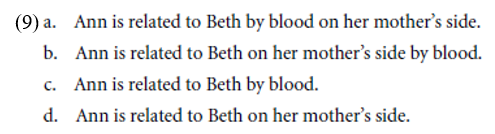

Next we will examine a case in which adverbial modifiers of a state verb clearly do exhibit the Davidsonian pattern. Mittwoch (2005) points out that the sentences in (9) have all three of the Davidsonian properties: Permutation, Drop, and Non-Entailment. As she notes, (9a) and (9b) are synonymous, each entails both (9c) and (9d), and neither is entailed by the conjunction of (9c) and (9d).

Beth may, after all, be Ann’s mother’s sister-in-law and Ann’s father’s sister. These examples raise interesting and important issues.3 In particular what they point out is that there is true relation modification (as discussed by McConnell-Ginet 1982). There is certainly no question that relations are objects in the domain of semantic interpretation. Transitive verbs and adjectives (and relational nouns) clearly denote relations, and relations can clearly have properties. My suggestion, then, is that the modifiers in (9) are, essentially, modifying a relation.

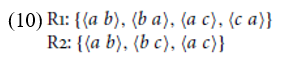

Let me give a mathematical example. We are familiar with a number of abstract properties that formal relations can have, such as transitivity, symmetry, reflexivity, and so on. These are second-order properties of relations. We are also familiar with the notion of a subrelation. It is, then, easy to define the notion of a relational modifier to be a function that takes a relation to a subrelation that has a given property. In (10) I specify (in set-of-pairs notation) two relations on the domain {a, b, c}. R1 has the property of being symmetric and R2 has the property of being transitive.

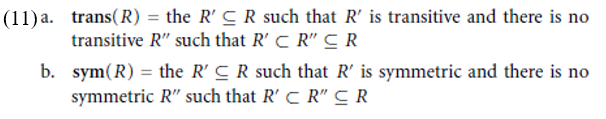

Note that a stands both in a symmetric relation to b and in a transitive relation to b, but not in a symmetric transitive relation to b. We can define the “modifying” operators sym and trans as follows:

It is easy to see that these modifiers have the Davidsonian properties Permutation, Drop, and Non-Entailment. If we let R0 = R1 ∪ R2 = {_a b_,_b a_, _a c_, _c a_, _b c_} we see that trans(R0) = {_a b_, _b c_, _a c_} = R2 and sym(R0) = {_a b_, _b a_, _a c_, _c a_} = R1; so that trans(R0) ∩ sym(R0) = {_a b_, _a c_} but trans(sym(R0)) = sym(trans(R0)) = {}. Clearly there is no event predication involved, however.

Returning to (9), the suggestion is that here too we have pure relation modification. Whether two individuals are related is determined by the existence of (chains of) two sorts of events – conceptions and marriages.4 For x to be related to y is, in general, for there be a chain of conceptions or marriages that relate x to y – I am related to my cousin Chris because the person who conceived me was conceived by the person who conceived the person who conceived Chris. This relation has certain properties, based on the properties that this chain of events has. I’m related to Chris on my father’s side because one of the individuals involved in the relevant conception events was my father, and I’m related to Chris by blood because none of the relevant events is a marriage.

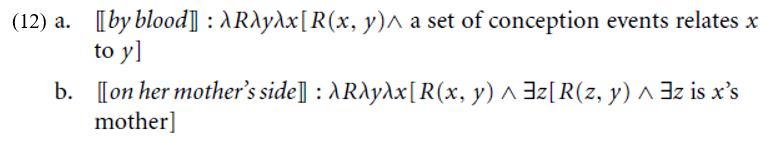

The modifiers by blood, by marriage, maternally, paternally, on his father’s side, and so on, specify the type of relation explicitly by specifying what properties these relevant events have. In general, if the events in the chains are only conceptions, it is a blood relation, if the chain includes x’s mother, it is a maternal relation, if the chain includes a marriage it is a relation by marriage. The modifiers, then, specify a (second-order) property of the personal relation, as indicated in (12).

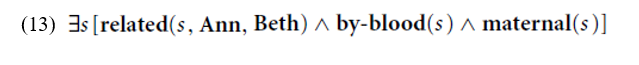

This is clearly not Davidsonian modification. In fact, Davidsonian-style modification of the type envisioned by Landman would actually be very little help here. A logical form such as that in (13) leaves open the question of how to determine whether a state is maternal or by blood.

To capture this would mean encoding, in the state domain, semantic information that already exists in the relation domain.

It does not appear, then, that we find compelling evidence for treating manner modifiers of state verbs in a Davidsonian fashion. If we reject such an analysis, the question becomes how to treat these modifiers, if not as Davidsonian-like co-predicates. We take this up in the next section.

3 An analogy might be drawn with such adjectival modifiers as current and proven which share the syntactic distribution of the non-intersective former and alleged (Siegel 1976a), i.e. their inability to appear in post-copular predicate position, but which are not non-intersective, at least inasmuch as they can be dropped. An alleged murder may not be a murder, but a proven murder is certainly a murder.

4 While clearly factive modifiers can be dropped preserving truth, this is quite obviously a somewhat different issue, again tied to lexical semantics. The fact that the adverb regrettably, for example, can be dropped is not a fact about speaker-oriented propositional modifiers in general, but about the lexical semantics of the adverb. This can be illustrated by contrasting regrettably with hopefully – there being entailment from (ia) to (ib) but none from (iia) to (iib).

(i) a. Regrettably, Katrin doesn’t like onions.

b. Katrin doesn’t like onions.

(ii) a. Hopefully, Anke will make kale.

b. Anke will make kale.

5 Parsons (1990) discussed cases like (i) which are in many ways similar.

(i) a. The door is connected to the frame at the base with a chain.

b. The door is connected to the frame with a chain.

c. The door is connected to the frame at the base.

He notes that such examples typically contain resultative adjectival predicates and suggests the possibility that the modifiers are (covertly) applied to these associated event predicates. Whether this is correct or not, we should note that the argument Mittwoch (2005) raises against it is flawed. While she rightly points out that (ii) doesn’t entail an illegal parking event (the actual parking might have been perfectly legal – what was illegal was the leaving the car there so long), what she overlooks is that illegal and in front of my house themselves have simple intersective meanings.

(ii) The car is illegally parked in front of my house.

(iii) a. The car is illegally parked.

b. The car is parked in front of my house.

These adverbs do not exhibit Non-Entailment: (ii) entails (iiia) and (iiib); but (iiia) and (iiib) together also entail (ii). Anything that is illegally parked and is parked in front of my house is illegally parked in front of my house.

6 Of course this is idealizing slightly – we must speak of conceptions that have led to a birth and of marriages that have not ended in divorce. There are also issues of adoption to consider. As none of this affects the central argument we will ignore these issues.

|

|

|

|

دراسة تكشف "مفاجأة" غير سارة تتعلق ببدائل السكر

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أدوات لا تتركها أبدًا في سيارتك خلال الصيف!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تؤكد الحاجة لفنّ الخطابة في مواجهة تأثيرات الخطابات الإعلامية المعاصرة

|

|

|