Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-08-05

Date: 2024-05-10

Date: 12-3-2022

|

Practical Uses of Phonological Analysis

Linguists are interested in finding out the patterned nature of speech for answers pertaining to psycholinguistics (the study of the interrelationship of language and cognitive structures and the acquisition of language), historical linguistics (the study of how languages change through time and the relationships among languages), and sociolinguistics (the study of the interrelationships of language and social structure of linguistic variation).

Besides its relevance in these areas, phonological analysis has great relevance in certain real-world applications that go beyond the confines of linguistics. To start with, there is an intimate relationship between an alphabetic writing system and the phonemic structure of a language. As such, the study of phonemics is highly useful for literacy experts, and to people devising orthographies for unwritten languages. This comes from the principle that assigns an orthographical letter for each ‘phoneme’ (not for each sound) in the language. Going back to the dental and alveolar nasals, [n̪] and [n], we discussed in relation to English and Malayalam, we can state that difference in the following manner: While the alphabetic representation of these two nasals will be sufficiently shown by one letter, n, in English (because the allophonic difference between [n̪] and [n] will be automatically supplied by native speakers of English), in the orthographic system of Malayalam we will have to have two distinct orthographic letters, because the two sounds are in contrast in this language. When we consider the two sounds [d] and [ð], with reference to Spanish and English, we come to the following conclusion: Spanish is well served by a single grapheme, d, for the sounds [d̪] and [ð], as in dedo [d̪eðo]. Since the two sounds are allophones of the same phoneme, speakers of Spanish automatically supply the predictable fricative allophone intervocalically. Thus, an additional grapheme for this predictable allophone will be an unnecessary duplication. When, on the other hand, we look at English, we realize that the language would require two distinct orthographical representations for these two sounds that are in contrast and belong to separate phonemes, as shown in the pair they [ðe] and day [de].

The reader was urged to ignore spelling and focus only on the sounds in studying phonetics and phonology. The reason for this is the many discrepancies that exist between phoneme and grapheme correspondences in English. The orthographic th, which stands for two separate phonemes, /T/ and /ð/ (e.g. ether [iθɚ] – either [iðɚ]), makes the point clearly. Had English spelling reflected an ideal alphabetic writing system (i.e. one grapheme to one phoneme), these two phonemes would be represented by two separate graphemes. We will have much more to say about English phonology and orthography later.

We can summarize what has been said in the following manner: alphabetic writing systems are ideally phonemic in that they target one phoneme to one grapheme. However, for several reasons in the history of a language, many discrepancies may develop and the current state of the orthography of a language may be far from ideal. Comparing the ir/regularity of the writing systems between languages, one hears remarks such as “the writing system of language X is phonetic”. Such remarks should not be taken seriously, because no alphabetic system ever targets being or aspires to be phonetic. What we want from an efficient writing system is to represent only the relevant (functional/phonemic) distinctions made in the language, and this precludes the introduction of separate graphemes for every predictable allophonic variation, as that would result in incredible complexity.

Besides the indispensable applications of devising alphabetical writing systems, the study of phonemics is a vital tool for foreign language teachers and for speech and language therapists. The common trait of the professionals in these two groups is that the populations they work with exhibit patterns (in sound systems, for our purpose) that are different from the ambient language, and thus should be remediated. Although the productions we observe in foreign language learners and individuals with phonological disorders are, to varying degrees, in disagreement with the norms of the ambient language, they nevertheless are not haphazard, but systematic. The importance of the application of phonological principles to the remediation setting stems from this patterned nature of the erroneous productions. In the remediation setting, information on the patterned nature of the productions to be corrected is crucial for arriving at an accurate diagnosis, and this in turn serves as the basis for effective remediation.

In many cases of erroneous productions, both in foreign language learners and in individuals with phonological disorders, we find several errors related not to the complete lack of a particular sound in the client’s system, but to the problems of distribution. To illustrate this, let us examine the following productions from a Japanese speaker who is learning English as a foreign language:

city [sɪtʃi], team [tʃim], totem [totεm], tune [tsun], tea [tʃi]

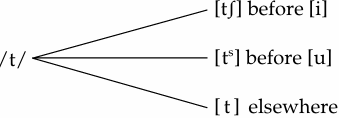

As we see, the renditions for the /t/ targets of English are varied: correct in totem, [tʃ] in city, team, and tea, and [ts] in tune. While the situation may initially look rather chaotic, a more careful look at the productions shows that the erroneous renditions in the form of [tʃ] and [ts] are not random, but systematic. Namely, the /t/ target of English is realized as [tʃ] if it is followed by /i/, and is realized as [ts] if it is followed by /u/. When the target /t/ is followed by any other sound, the learner’s renditions are correct. The explanation for these phenomena is directly related to the learner’s native language patterns, which can be illustrated as follows:

What the learner is doing is transferring the native rule to the English learning context. Such events, which are known as native language interference, form the central core of the field known as contrastive phonology, and will be dealt with in greater detail later.

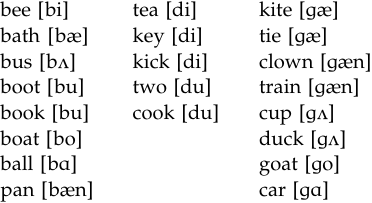

The importance of an accurate phonological profile of the learner for effective remediation has also been recognized in the clinical setting. A disordered system may also be a system with its own patterning and distribution that are not identical to those of the ambient system. The therapist, like the language teacher, needs to know the details of the system before any attempt at treatment is made. Consider the following data from a three-year-old who has the phonetic capacity to produce the target voiced stops /b, d, g/ but has distributional problems (Camarata and Gandour 1984):

We can see that the child has the contrast between the bilabial and alveolar voiced stops, as revealed by bee [bi] versus tea [di]. On the other hand, we do not have a contrast between the alveolar and the velar. What we gather from the productions is that the client shows a case of complementary distribution between these two; [d] appears before high vowels (second column), and [g] appears before non-high (low or mid) vowels (third column). Once again, we have a situation in which the initially chaotic-looking productions that present mismatches with the ambient language have systematic patterns that could be exploited in therapy.

Cases such as the ones described above can be easily multiplied in L2 (second language) classroom and clinical contexts, and make it clear that familiarity with the phonemic analysis is indispensable for L2 teachers and therapists.

|

|

|

|

دخلت غرفة فنسيت ماذا تريد من داخلها.. خبير يفسر الحالة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ثورة طبية.. ابتكار أصغر جهاز لتنظيم ضربات القلب في العالم

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ووفد من جامعة البصرة يبحثان سبل تعزيز التعاون المشترك

|

|

|