Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-05-04

Date: 2024-05-01

Date: 24-3-2022

|

Let us consider in detail an example of a global derivational constraint,1

(1) Many men read few books.

(2) Few books are read by many men.

In my speech, (1) and (2) are not synonymous.

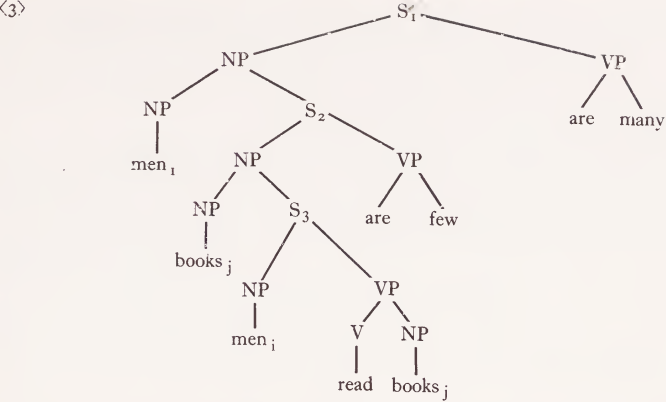

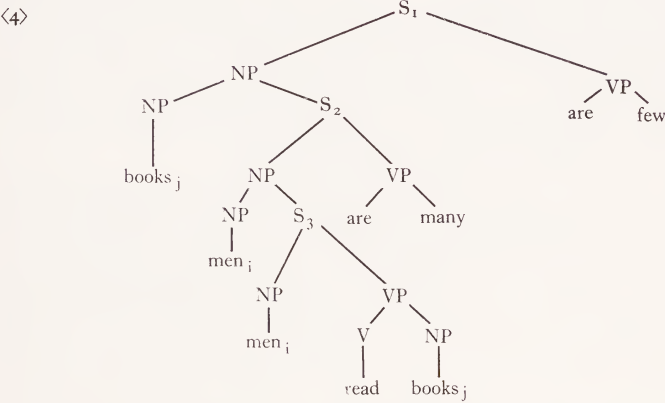

Sentences like (1) and (2) were brought up in a discussion by Partee [55] with regard to certain inadequacies of a proposal made in Lakoff [40] for the derivation of quantifiers from predicates of higher sentences. That proposal was suggested by the observation that sentences like ‘ Many men left ’ are synonymous with those like the archaic4 The men who left were many.’ It was proposed that sentences like the former were derived from structures underlying sentences like the latter, with ‘ many ’ as an adjective, which is then lowered. Under such a proposal, underlying structures like {3) and (4) would be generated :2

(3') Many are the men who read few books. There are many men who read few books.

(4') Few are the books that many men read. There are few books that many men read.

In (3), a cyclical rule of quantifier-lowering will apply on the S2-cycle, yielding meni read few books. The same cyclic rule will apply on the S1-cycle, lowering many onto meni and yielding (1), many men read few books.

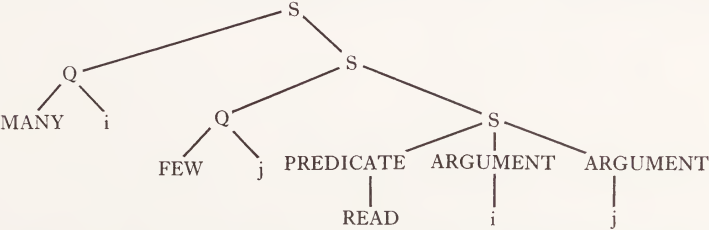

to the domain of men. For the purpose of this argument, representations of the following sort (which are somewhat closer to reality) can be used in the place of representations like )3):

where: i is restricted to the domain of men and j is restricted to the domain of books.

In (4) let us suppose that the passive, a cyclical rule, applies on S3, before any quantifier-lowering takes place: this will give us booksj are read by meni. On the S2-cycle, many will be lowered onto meni, yielding booksj are read by many men. On the S1-cycle,few will be lowered onto booksj giving (2), few books are read by many men.

These derivations work as they should and account for the synonymy of (1) with (3') and (2) with (4'). However, if nothing more is said, this proposal will yield incorrect results. For example, if the passive applies to S3 in (3), we will get booksj are read by men1, and then quantifier-lowering on the S2- and S1-cycles will yield (2),few books are read by many men. But if (2) were derived from (3) in this fashion, it should be synonymous with (3'), many are the men who read few books. This is false, and such a derivation must be blocked. Similarly, if the passive were not to apply to S3 in (4), the application of quantifier-lowering on the S2- and S1-cycles would yield (1), many men read few books, again a mistake, since (1) does not have the meaning of (4'), few are the books that many men read.

Such a proposal would work in the first two cases, but would also predict the occurrence of two derivations that do not occur, at least for the majority of English speakers. If one inspects (1)-(4), one notices that the correct derivations have the property that the ‘higher’ quantifiers in (3) and (4) are the leftmost quantifiers in (1) and (2) respectively. Thus, we might propose a derivational constraint that would say something like: if one quantifier commands another in underlying structure (or rather, P1), then that quantifier must be leftmost in surface structure. Such a constraint as it stands would be too strong. Consider cases like (5):

(5) The books that many men read are few (in number).

(5) would have an underlying structure like (4), where few is the higher quantifier; however, few is to the right of many in surface structure. Thus cases like (5) would have to be ruled out of any such derivational constraint. If one inspects (2) and (5), one sees that they differ in the following way. In (5) few commands many, but many, being in a relative clause, does not command few; that is, few is higher in the tree than many in (5) just as it is in the underlying structure of (4). In other words, (5) preserves the asymmetric command-relationship between the quantifiers that occurs in (4). In (2) however, this is not the case. In (2), neither few nor many is in a subordinate clause, and so each commands the other and the command-relationship is symmetric. Thus the asymmetry of the command-relationship in the underlying structure, where few commands many but many does not command few is lost in (2). It is exactly these cases where the quantifier that was higher in underlying structure must be leftmost in surface structure. Where the asymmetric command-relationship is lost it must be supplanted by a precede-relationship, which is necessarily asymmetric.

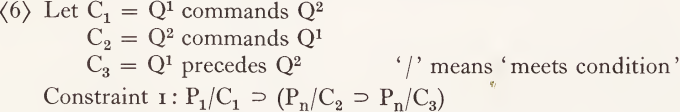

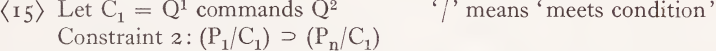

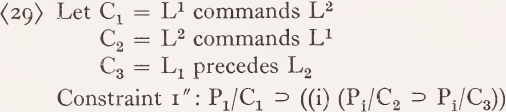

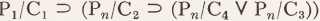

Such a derivational constraint may be stated as follows:

Constraint 1 states that if two quantifiers Q1 and Q2 occur in underlying structure P1, such that P1 meets condition C1, then if the corresponding surface structure Pn meets condition C2, that surface structure Pn must also meet condition C3. In short, if an underlying asymmetric command-relationship breaks down in surface structure, a precede-relationship takes over. Constraint 1 is a well-formedness constraint on derivations. Any derivation not meeting it will be blocked. Thus, the derivations

(3) ---> (1) and (4) ---> (2) will be well-formed, but (3) ----> (2) and (4) ----> (1) will be blocked.

It is important to note that the fact that one of the two quantifiers is in subject position in the sentences we have discussed so far is simply an accident of the data we happened to have looked at. The difference in the interpretation of quantifiers has nothing whatever to do with the fact that in these examples one quantifier is inside the VP while the other is outside the VP. Only the left-to-right order within the clause matters.

(7) John talked to few girls about many problems.

(8) John talked about many problems to few girls.

These sentences differ in interpretation just as do (1) and (2), that is the leftmost quantifier is understood as the highest in each sentence, though both quantifiers are inside the VP.

Although (1) and (2) are cases where the asymmetry of the underlying command-relationship disappears in surface structure, it happens to be the case in (1) and (2) that condition C1, which holds in underlying structure, continues to hold in surface structure: that is, Q1 continues to command Q2. We might ask if there exist any cases where this does not happen, that is, where Q1 commands Q2 in underlying structure, but Q1 does not command Q2 in surface structure. A natural place to look for such cases, and perhaps the only one, is in sentences containing complement constructions. Let us begin by considering sentences like (9):

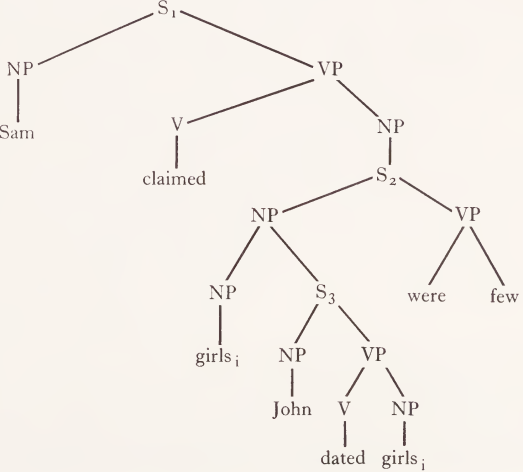

(9) Sam claimed that John had dated few girls.

(9) is open to both of the readings (10) and (11), though (10) is preferable:

(10) Sam claimed that the girls who John had dated were few (in number).

(11) The girls who Sam claimed that John had dated were few (in number).

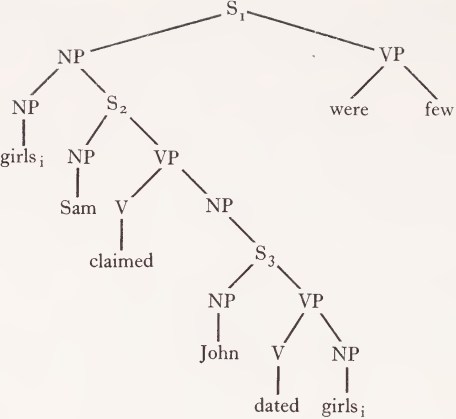

(10) and (11) would have underlying structures like (10') and (11') respectively:

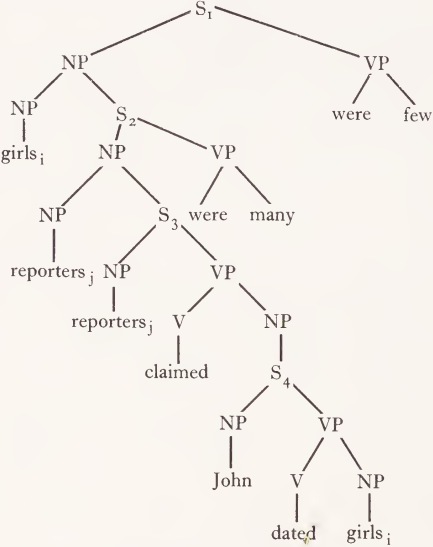

(10’)

(11’)

In each case quantifier-lowering will move few down to girlsi. In (10), girlsi occurs in the S immediately below few; in (11), girlsi occurs two sentences down from few. We are now in a position to test the conjecture that one quantifier may cease to command another in the course of a derivation. Consider (12), where fem commands many:

(12)

(12’) would have the meaning of (12'):

(12') Few were the girls who many reporters claimed John dated.

If we allow quantifier-lowering to apply freely to (12), many will be lowered to reportersj on the S2 cycle, yielding many reporters claimed that John dated girlsi. The derived structure will now look just like (11), except that it will have the noun phrase many reporters instead of Sam. As in (11), quantifier-lowering will lower few onto girlsi yielding (13):

(13) Many reporters claimed that John dated few girls.

In (13),few is in a subordinate clause and does not command many. Thus we have a case where few commands many in underlying structure, but not in surface structure. Note, however, that (13) does not have the meaning of (12'). It has the reading of :

(14) Many were the reporters who claimed that the girls who John dated were few (in number).

where few is inside the object complement of claim (as in (10)) and where many would command few in underlying structure. Thus, we have a case where a derivation must block if one quantifier commands another in underlying structure, but not in surface structure. To my knowledge this is a typical case, and I know of no counterevidence. Thus, it appears that a derivational constraint of the following sort is needed:

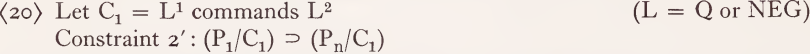

Constraint 2 says that if Q1 commands Q2 in underlying structure P1, then Q1 must also command Q2 in surface structure Pn.

Constraints 1 and 2 are prime candidates for cases where grammatical constraints seem to reflect perceptual strategies. If one considers a perceptual model where surface strings are given as input and semantic representations are produced as output, constraints 1 and 2 guarantee that the relative heights of the quantifiers in the semantic representation of a sentence can be determined by the surface parsing of the sentence. If Q1 commands Q2 in surface structure but Q2 doesn’t command Q1, then Q1 commands Q2 in semantic representation. If, on the other hand, Q1 and Q2 command each other in surface structure, then the leftmost quantifier commands the rightmost one in semantic representation. If constraints 1 and 2 are reflections in grammar of perceptual strategies, then they would of course be prime candidates for syntactic universals. Unfortunately for such a proposal, there is a lot of idiosyncratic variation with such constraints.

Constraint 2 does not simply hold for quantifiers, but for negatives as well. Consider, for example, (16):

(16) Sam didn’t claim that Harry had dated many girls.

where many does not command not. If quantifier-lowering worked freely one would expect that (16) could be derived from all of the following underlying structures:

(17) [s not [s Sam claimed [sgirlsi [Harry dated girlsi] were many]]]

(18) [s not [s girlsi| [sSam claimed [sHarry dated girlsi]] were many]]

(19) [sgirlsi [snot [sSam claimed [sHarry dated girlsi]] were many]

These have the senses of:

(17') Sam didn’t claim that the girls who Harry dated were many.

(18') There weren’t many girls who Sam claimed Harry dared.

(19') There were many girls who Sam didn’t claim Harry dated.

(17) is the normal reading for (16); (18) is possible, but less preferable (like (11)); but (19) is impossible. The regularity is just like that of Constraint 2. In (17) and

(18), not commands many in underlying structure, just as in surface structure (16). In (19) many commands not in underlying structure, but many does not command not in surface structure (16). Thus we can generalize constraint 2 in the following way. Let L stand for a ‘ logical predicate ’, either Q or NEG.

Conditions of this sort suggest that quantifiers and negatives may form a natural semantic class of predicates. This seems to be confirmed by the fact that Constraint 1 can be generalized in the same fashion, at least for certain dialects of English. Consider, for example, the following sentences discussed by Jackendoff [32], [33]:

(21) Not many arrows hit the target.

(22) Many arrows didn’t hit the target.

(23) The target wasn’t hit by many arrows.

Jackendoff reports that in his speech (23) is synonymous with (21), but not (22). I and many other speakers find that (23) has both readings, but that the (22) reading is ‘weaker’; that is, (23) is less acceptable with the (22) reading. However, there are a number of speakers whose dialect displays the facts reported on by Jackendoff, and in the remainder of this discussion we will be concerned with the facts of that dialect.

Assuming the framework discussed above, (21) and (22) would have underlying structures basically like (24) and (25):

(24) [S not [S arrowsi [S arrowsi hit the target] were many]]

(24') The arrows that hit the target were not many.

(25) [Sarrowsi [S not [Sarrowsi hit the target]] were many]

(25') The arrows that didn’t hit the target were many.

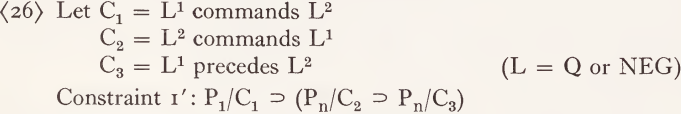

If constraint 1 is generalized to include ‘logical predicates’, both negatives and quantifiers, then the facts of (2i)-(23) will automatically be handled by the new constraint 1’ given the underlying structures of (24) and (25) and the rule of quantifier-lowering. Constraint 1’ would be stated as (26):

Any derivation not meeting this condition will be ill-formed.3

(21) and (22) work as expected. Take (21): not (L1) commands many (L2) in underlying structure (24), many commands not in surface structure (21), and not precedes many in surface structure. So (24) ----> (21) meets constraint 1. Take (22) : many (L1) commands not (L2) in underlying structure (25) and in surface structure, not commands many in surface structure, and many precedes not in surface structure. So (25) ----> (22) meets constraint 1. Now consider (23), which is the interesting case in this dialect. If one allows the passive transformation to apply to the innermost S of (24) and (25), and then allows quantifier-lowering to apply, both (24) and (25) will yield (23). First consider the derivation (24) ----> (23). Not (L1) commands many (L2) in underlying structure (24) and in surface structure, many commands not in surface structure (21), and not precedes many in surface structure. Thus, the derivation (24) ----> (23) meets constraint 1. Now consider the derivation (25) ----> (23). Many (L1) commands not (L2) in underlying structure and in surface structure, not commands many in surface structure (23), but many (L1) does not precede not (L2) in surface structure (23). Therefore, the derivation (25) ----> (23) does not meet constraint 1, and so the derivation is blocked. This accounts for the fact that (23) is not synonymous to (21) and that there is no passive corresponding to (25) in this dialect.

It should also be noted that that part of constraint 1’ which says that L2 must command L1 in surface structure (Pn / C2) if the precede-relationship (Pn / C2) is to come into play, is necessary for the cases discussed. Consider, for example, sentence (25'), The arrows that didn't hit the target were many. In (25'), many (L1) commands not (L2) in P1 and many also commands not in Pn. Thus, the if part of the conditional statement of constraint T is not met, and the fact that not (L2) precedes many (L1) in surface structure (that is, that (Pn / C3) does not hold) does not matter; since the if-condition is not met, the constraint holds and the sentence is grammatical with the reading of (25).

We have assumed so far that constraints 1’ and 2' mention the surface structure. But this is just an illusion which results from considering only simple sentences. Suppose, for example, that we consider complex sentences where deletion has taken place. Consider (27) and (28):

(27) Jane isn’t liked by many men and Sally isn’t liked by many men either.

(28) Jane isn’t liked by many men and Sally isn’t either.

Note that the sentence fragment Sally isn't either does not contain many in surface structure, but it receives the same interpretation as the full Sally isn't liked by many men either, and does not have the reading of There are many men who Sally isn't liked by. Constraint 1’ as it is presently stated will not do the job, in that it mentions surface structure Pn rather than some earlier stage of the derivation prior to the deletion of liked by many men.

This raises a general problem about constraints like 1’ and 2'. Since they only mention underlying structures P1 and surface structures Pn, they leave open the possibility that such constraints might be violated at some intermediate stage of the derivation. My guess is that this will never be the case, and if so, then it should be possible to place much stronger constraints on derivations than 1' and 2’ by requiring that all intermediate stages of a derivation Pi meet the constraint, not just the surface structure Pn. Using quantifiers, we can state such a stronger constraint as follows:

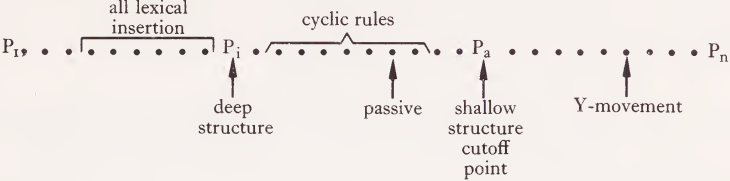

(29) will now automatically handle cases like (28), since it will hold at all points of the derivation up to the point where the deletion rule applies; after that point, it will hold vacuously. The reason is that many will not appear in any phrase-marker after the deletion takes place and so C2 will not hold in such phrase-markers; and where C2 does not hold, then C3 need not hold.

However, this is still insufficient, since Constraint 1" still requires that if C2 holds in surface structure, then C3 must hold in surface structure, as well as in earlier stages of a derivation. But there are late rules which make gross changes in derived structure and produce surface structures in which the constraints do not hold. Compare (30) and (31):

(30) Sarah Weinstein isn’t fond of many boys.

(31) Fond of many boys, Sarah Weinstein isn’t.

The rule of Y-movement as discussed in Postal [57] will produce (31) from the structure underlying (30). (Needless to say, (31) is not grammatical in all American dialects. We are considering only those in which (31) is well-formed.) Note that (30) works exactly according to constraint 1"; the reading in which many commands not in P1 is blocked since many does not precede not in surface structure. But (31), where the surface order of not and many is reversed, shows the same range of blocked and permitted readings as (30). The outputs of Y-movement do not meet constraint 1", though earlier stages of the derivation do. Thus, it appears that constraint 1" has some cutoff point prior to the application of Y-movement. That is, there is in each derivation some ‘shallow structure’ Pa defined in some fixed way such that

This raises the interesting question of exactly how the ‘shallow structure’ Pa is to be defined. One possibility is that Pa is the output of the cyclical rules. However, there aren’t enough facts known at present to settle the issue for certain. Still, we can draw certain conclusions. Passive, a cyclic rule, must be capable of applying before Pa, since constraint 1" must apply to the output of passive. Y-movement must apply after Pa.

Let us now consider the constraints we have been discussing with respect to the process of lexical insertion. Let us constrain the basic theory so that some notion of ‘deep structure’ can be defined along the lines discussed above. Let it be required that all lexical insertion rules apply in a block and that all upward-toward-the-surface cyclic rules apply after lexical insertion. Since passive is a cyclic rule and since passive must be able to apply before Pa is reached, it follows that if there is such a ‘deep structure’ all lexical insertion must occur before Pa is reached. Thus, it is an empirical question as to whether such a notion of ‘deep structure’ is correct. If there exist lexical items that must be inserted after Pa, then such a notion of ‘deep structure ’ would be untenable since there would exist upward-toward-the-surface cyclic rules (e.g., passive) which could apply before some case of lexical insertion.

Empirical question: Does there exist a lexical item that must be inserted between Pa and Pn? If so, then ‘deep structure’ does not exist.

Let us pursue the question somewhat further. Consider the sentences

(32) (a) I persuaded Bill to date many girls.

(b) I persuaded many girls to date Bill.

(33) (a) I persuaded Bill not to date many girls.

(b) I persuaded many girls not to date Bill.

(34) (a) I didn’t persuade Bill to date many girls.

(b) I didn’t persuade many girls to date Bill.

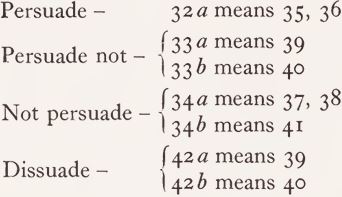

If we consider the meanings of these sentences, it should be clear that these cases work according to the two derivational constraints that we have stated thus far.

The difference in the occurrence of not is crucial in these examples. In (33), not in semantic representation would occur inside the complement of persuade, while in the semantic representation of (34) not will occur in the sentence above persuade. That is, in (33) persuade commands not in SR, while in (34) not commands persuade. This difference in the occurrence of not accounts for the fact that (33 a) is unambiguous, while (32a) and (34a) are ambiguous. (32a) can mean either (35) or (36):

(35) There were many girls that I persuaded Bill to date.

(36) I persuaded Bill that the number of girls he dates should be large.

(34a) can mean either (37) or (38):

(37) There weren’t many girls that I persuaded Bill to date.

(38) It is not the case that I persuaded Bill that the number of girls he dates should be large.

But (33 a) can mean only (39):

(39) I persuaded Bill that the number of girls he dates should not be large.

The reason (33a) is unambiguous is that since not precedes many in derived structure, not must command many in underlying structure (by constraint 1"). Since not originates inside the complement of persuade, and not must command many, many must also originate inside the complement of persuade. In (32a) and (34a), many may originate either inside the complement of persuade or from a sentence above persuade, which accounts for the ambiguity.

Now compare (33 b) and (34 b). In (33 b) many both precedes and commands not in derived structure; therefore, many must command not in underlying structure. (33 b) only has the reading of (40):

(40) There were many girls that I persuaded not to date Bill.

In (34 b), on the other hand, not precedes many in derived structure and so must command many in underlying structure. So (34 b) can mean (41) but not (40).

(41) There weren’t many girls that I persuaded to date Bill.

Let us now consider the lexical item dissuaded.4

(42)(a) I dissuaded Bill from dating many girls.

(b) I dissuaded many girls from dating Bill.

In (42) the word not does not appear. The only overt negative element is the prefix dis-. Thus, the postlexical structure of (42 ) would not have the negative element inside the object complement of -suade, but in the same clause, as in (43):

(b) I NEG-suaded many girls from dating Bill.

Moreover, the negative element would precede rather than follow the object of dissuade. In terms of precede- and command-relations, the postlexical structure of (42) would look like (34) rather than (33). Suppose Pa were postlexical, that is, suppose that the command-relationship between not and many in semantic representation were predictable from the precede-relationship at some point in the derivation after the insertion of all lexical items. We would then predict that since NEG precedes many in (42), NEG must command many in the underlying structure of (42). That is, we would predict that the sentences of (42) would have the meanings of (34). That is, we would predict that the sentences of (42) would have the meanings of (34). But this is false. (42a) and (42 b) have the meanings of (33 a) and (33 b).

Summary of Majority Dialect5

Dissuade means persuade -NP - not rather than not-persuade-NP, and the constraints on the occurrence of quantifiers in derived structure reflect this meaning, and must be stated prelexically. The lexical item dissuade must be inserted at a point in the derivations of (33) and (34) after constraint 1"' has ceased to operate. Now recall that constraint 1"' must operate on the output of the passive transformation. Consider (44):

(44) (a) Many men weren’t dissuaded from dating many girls.

(b) Not many men were dissuaded from dating many girls.

(c) I didn’t dissuade many men from dating many girls.

(44) shows the characteristics of both (34) and (21)-(23). In (44), constraint 1" must operate both after the passive transformation and before the insertion of dissuade. Thus we have cases where an upward-toward-the-surface cyclic rule must apply before the insertion of some lexical item. This shows that any conception of ‘deep structure’ in which all lexical insertion takes place before any upward-toward-the-surface cyclic rules apply is empirically incorrect. It also shows that the passive transformation may apply to a verb before the overt lexical representation of the verb is inserted, which means that prelexical structures must look pretty much like postlexical structures. In the case of dissuade, one might be tempted to try to avoid such a conclusion with the suggestion that dissuade is derived by a relatively late transformation from a structure containing the actual lexical item persuade. Under such a proposal, dissuade would not be introduced by a rule of lexical insertion, but rather by a rule which changes one actual lexical item to another. Such a solution cannot be made general, however, since lexical items like prohibit, prevent, keep, forbid, etc., which do not form pairs like persuade-dissuade, work just like dissuade with respect to the properties.

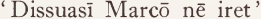

A particularly tempting escape route for those wishing to maintain a level of ‘deep structure’ might be the claim that the lexical item dissuade is inserted pre-cyclically, that dissuade requires a not in its complement sentence, and that this not is deleted after shallow structure. Thus, the not would be present at the time that the constraints shut off, and all of the above facts would be accounted for. This proposal has some initial plausibility since similar verbs in other languages often have a negative element that appears overtly in its complement sentence. For example, in Latin we have  (I dissuaded Marcus from going), where nē, the morphological alternant of nōn in this environment, occurs in the complement sentence.

(I dissuaded Marcus from going), where nē, the morphological alternant of nōn in this environment, occurs in the complement sentence.

Let us suppose for the moment that such a solution were possible. This would mean that the complement sentence of dissuade would contain a not at the level of shallow structure, but not at the level of surface structure. Now consider the following sentences:

(45) I dissuaded Mary from marrying no one.

(46) *I persuaded Mary not to marry no one.

(47) *Mary didn’t marry no one.

(48) I didn’t persuade Mary to marry no one.

(46) and (47) are ungrammatical in standard English, and in all dialects if the two negatives are both considered as underlying logical negatives (e.g., if (47) has the reading It is not the case that Mary married no one). As is well known, this prohibition applies only for negatives in the same clause (cf. example (48), where the negatives are in different clauses). The question arises as to where in the grammar the No-double-negative (NDN) constraint is stated, (a) If ‘ deep structure ’ exists, it could be stated there; (b) it could be stated at shallow structure; (c) it could hold at all levels between deep structure and shallow structure; or (d) it could hold only at surface structure.

Now consider (45). Under the above proposal for post-shallow-structure deletion of not in dissuade-stntencts, not would still be present at the level of shallow structure. (In fact, it would be present at all points between deep structure and shallow structure, that is, all points in the derivation where constraints 1 and 2 hold.) At the level of shallow structure, (45) would have the form:

(45') I dissuaded Mary from not marrying no one.

Thus under the above proposal, the No-double-negative (NDN) constraint could not hold at the level of shallow structure, or at any previous point in the derivation back to deep structure; if it did, (45) would be ruled out. Thus, under the proposal for post-shallow-structure not-deletion, the NDN-constraint could only be a constraint on surface structure, not on shallow structure. Let us now take up the question of whether this is possible.

The following sentences are in accord with the NDN-constraint whether it holds at shallow or surface structure, since these sentences have essentially the same representation at both levels.

(49) Max said that Sheila Weinstein was spurned by no one.

(50) Max didn’t say that Sheila Weinstein was spurned by no one.

(51) *Max said that Sheila Weinstein wasn’t spurned by no one.

Note that in the appropriate dialects, Y-movement can apply to sentences of this form moving the participal phrase of the embedded clause.

)52) Max said that Sheila Weinstein wasn’t spurned by Harry.

(53) Spurned by Harry, Max said that Sheila Weinstein wasn’t.

In (53), Harry has been moved from a position where it was in the same clause as n't to a position where it is in a higher clause. Now consider once more:

(51) *Max said that Sheila Weinstein wasn’t spurned by no one.

If the NDN-constraint holds for surface, not shallow, structures, then the application of Y-movement to (51) would move no one out of the same clause as n't and should make the NDN-constraint nonapplicable at surface structure. Thus, (54) should be grammatical:

(54) *Spurned by no one, Max said that Sheila Weinstein wasn’t.

But (54) is just as bad as (51) - the NDN-constraint applies to both. As we have seen, the NDN-constraint cannot apply to the surface structure of (54), since no one is not in the same clause as n't, having been moved away by Y-movement. Thus, in order to rule out (54), the NDN-constraint must apply before Y-movement; that is, it must apply at the level of shallow structure.

But this contradicts the post-shallow-structure not-deletion proposal, since under that proposal (45), which is grammatical, would contain two negatives in the same clause at the level of shallow structure (cf. (45')). Thus, the post-shallow-structure not-deletion proposal is incorrect.

A similar proposal might say that prior to shallow structure, from replaced not with verbs like dissuade and prevent, while to replaced not with a verb like forbid, and that from and to ‘ acted like negatives ’ (whatever that might mean) with respect to constraints 1 and 2 at shallow structure and above. However, it is clear from sentences like (45) that from does not act like a negative with respect to the NDN-constraint at shallow structure. Such a proposal would thus require from both to act like a negative and not to act like a negative, a contradiction. Neither of these routes provides an escape from the conclusion that dissuade must be inserted after shallow structure.

Another route by which one might attempt to avoid this conclusion would be by claiming that derivational constraints did not operate on the internal structure of lexical items, and that therefore dissuade could be inserted before the passive, preserving the notion of ‘ deep structure ’. It would then not interact with the constraints. Such a claim would be false. Dissuade does interact with the constraints. As the summary of meaning-correspondences given above shows, dissuade acts just like persuade not, not like persuade. In particular, (42 a) is unambiguous, just like (33 a). It only has a reading with many originating inside the complement, as the constraints predict. If dissuade were impervious to the constraints, then we would expect it to act like persuade; in particular, we would expect (42 a) to be ambiguous, just like (32 a), where many may be interpreted as originating either inside or outside of the complement. But as we have seen, (42 a) does not have the outside reading. John dissuaded Bill from dating many girls cannot mean Many were like girls who John dissuaded Bill from dating.

It should be noted that this argument does not depend on the details of constraint I" being exactly correct. It would be surprising if further modifications did not have to be made. Nor does this argument depend on any prior assumption that semantic representation must be taken to be phrase-markers, though the discussion was taken up in that context. It only depends on the facts that persuade-not and not-persuade obey the general constraints on quantifiers and negatives, and that dissuade acts like persuade-not. Thus, in any version of transformational grammar there will have to be stated a general principle relating semantic representations of sentences containing quantifiers and negatives to the left-to-right order of those corresponding quantifiers and negatives in ‘derived structure’. If the general principle is to be stated, the notion ‘derived structure’ will have to be defined as following the passive rule, but preceding the insertion of dissuade. Thus, in no non-ad-hoc transformational grammar which states this general principle will all lexical insertion precede all cyclical rules.

Let us sum up the argument.

(i) Suppose ‘deep structure’ is defined as a stage in a derivation which follows the application of all lexical insertion rules and precedes the application of any upward-toward-the-surface cyclic rules.

(ii) Evidence was given for derivational constraints 1 and 2, which relate semantic command-relationships to precede- and command-relationships at some level of ‘derived structure ’.

(iii) But the passive transformation must precede the insertion of lexical items such as dissuade, prohibit, prevent, keep, etc.

(iv) Since passive is an upward-toward-the-surface cyclic rule, (iii) shows that the concept of ‘deep structure ’ given in (i) cannot be maintained.

1 It should be noted at the outset that all of the sentences discussed are subject to dialect variation. At least one-third of the speakers I have encountered find (1) and (2) both ambiguous. The sentences to be discussed in the remainder are subject to even greater variation, especially when factors like stress and intonation are studied closely. The data I will present below correspond to what I take to be the majority dialect. I take note of cases where my speech differs from that dialect, and a more thorough discussion of dialect differences will be given, after the discussion of the general constraints. It is especially important to remember throughout that the argument to be presented depends on the existence of a single dialect for which the data presented are correct. It is not even important that the dialect described by these data be the majority dialect, though, so far as I can tell, it is.

2 The structures given in (3) and (4) are not meant to be taken seriously in all details. They are based on a 1965 analysis which mistakenly followed Chomsky in assuming a level of deep structure containing all lexical items and having nodes such as VP Since then such assumptions have been shown to be erroneous. I am using these particular structures only for historical reasons, since Partee [55] uses them in her paper. The main point at issue is whether quantifiers in underlying syntactic representations are in a higher clause than the NPs they quantify (as in predicate calculus) or whether they are part of the NPs they quantify (as they are in surface structure). Expressions such as ‘men,-’ are to be understood as the variable i limited where: i is restricted to the domain of men and j is restricted to the domain of books.

3 I have ignored the role of stress in this discussion, though it is of course important for many speakers. Many people find that (i)

(i) Many men read few books.

where few has extra heavy stress can mean The books that many men read are few. Thus, the general principle here seems to be that where the asymmetric command relation is lost in derived structure, then either one or another of what Langacker calls ‘ primacy relations ’ must take over. One which I would propose is the relation ‘has much heavier stress than’; the other is the relation ‘precedes’. These relations seem to form a hierarchy with respect to this phenomenon in such dialects:

1. Commands (but is not commanded by)

2. Has much heavier stress than

3. Precedes.

If one quantifier commands but is not commanded by another in surface structure, then it commands in underlying structure. If neither commands but is not commanded by the other in surface structure, then the one with heavier stress commands in deep structure. And if neither has much heavier stress, then the one that precedes in surface structure commands in underlying structure. Letting C4 = Q1 has much heavier stress than Q2, the constraint for such a dialect could be stated as follows, though the notation is not an optimum one for stating such a hierarchy:

Since the dialect with this condition is in the minority so far as I have been able to tell from a very small amount of study, I will confine myself to the normal dialect in the remainder of the discussion.

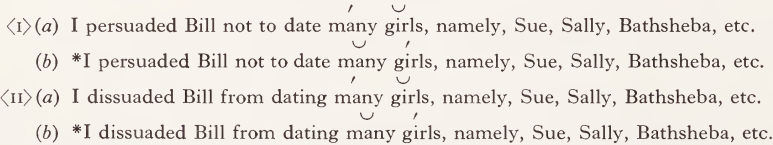

4 As noted in footnote a, p. 244, the constraints under discussion require that the quantifiers be unstressed. The facts of (42), as I describe them for my dialect will, of course, not hold if many receives heavy stress. Instead, many, as indicated in that footnote, can then be understood as the highest quantifier. This is, of course, equally true in the dissuade and persuade not cases. The following examples should make this clear.

In the (a) sentences, where many is stressed, many can be interpreted as commanding not. In that case, one is talking about particular girls, and so enumerations with namely are possible. When many is unstressed, it cannot be interpreted as commanding not, and consequently it cannot be taken as picking out particular girls. Hence, enumerations with namely are not possible.

5 Though these facts seem to hold for the majority of speakers I have asked, they by no means hold for all. There is even one speaker I have found for whom the crucial case discussed here does not hold. This speaker finds that dissuade does not work like persuade not with respect to ambiguities. For him, (42a) can mean not only (39), but also There were many girls that I dissuaded Bill from dating, even when (42 a) does not contain stress on many. This speaker seems to have a constraint that holds just at the level of surface structure, and not at the level of shallow structure or above. Interestingly enough, the same speaker has the No-double-negative constraint discussed below in the same form as the majority of other speakers, only for him it holds at surface structure, not shallow structure. For him, (51) below is ungrammatical, but (54) is grammatical. Perlmutter has suggested that such variation in the constraints is due to the fact that children learning their native language are not presented with sufficient data to allow them to determine at which level of the grammar various constraints hold, or exactly which classes of items obey which constraints.

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اتحاد كليات الطب الملكية البريطانية يشيد بالمستوى العلمي لطلبة جامعة العميد وبيئتها التعليمية

|

|

|