Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-12-16

Date: 2023-10-21

Date: 13-6-2022

|

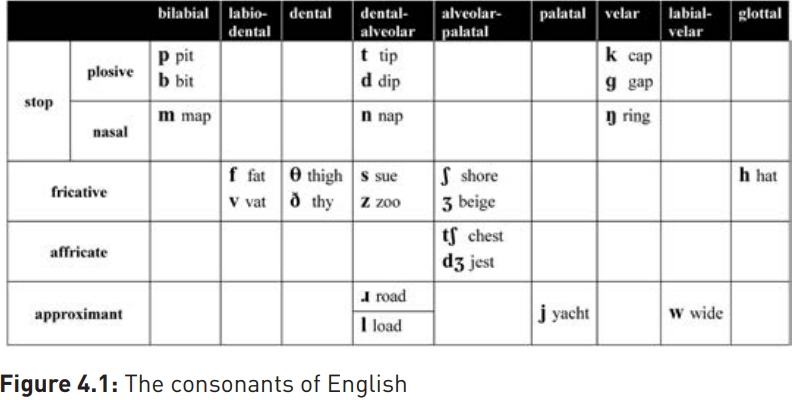

The consonants of English

Try pronouncing the word rapid, and then say rabid (to rhyme with rapid). Say these words together a few times, and pay particular attention to the middle sound in each case. You’ll notice that your lip and tongue positions are exactly the same for both words, but they are nonetheless quite distinct. The other sounds are not significantly different, so in what way are the consonants different? To answer this question, try saying just the p and b sounds, conveniently transcribed in IPA as [p] and [b] respectively, rapidly several times in succession, holding your larynx (or Adam’s apple) between thumb and forefinger as you do so. (Don’t be shy: you’re doing this for linguistic science.) Now do the same for t and d ([t] and [d] in IPA). You’ll feel your larynx vibrating for [b] and [d], but not for [p] and [t], because the former are voiced sounds, while [p] and [t] are voiceless.

We can therefore distinguish a number of pairs of speech sounds (or phones) on the basis of whether they are voiceless (like [p], [t] and [k] or voiced (like [b], [d] and [g]). We can now subdivide them further on the basis of their place of articulation. The [p] and [b] sounds you produced earlier, for example, are produced by the lips coming together and being released: the tongue is not really involved at all. These sounds are therefore bilabial. By contrast, for [t] and [d] the tongue touches the back of the teeth and the alveolar ridge to produce a dental-alveolar sound, while contact between tongue and soft palate produces the velar sounds [k] and [g]. Other English consonants are labio-dental (bringing bottom lip and top teeth together), palatal (the tongue meets the hard palate), alveolar-palatal (closure is made at the point where hard palate and alveolar ridge meet) or glottal (involving full or partial closure of the glottis). The full set of English consonants, with examples, is shown on the next page:

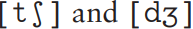

The final parameter for the description of consonants is manner of articulation, of which five kinds are relevant to English. When you produced [p] and [b] earlier, you felt a build-up of air pressure behind your lips, which was suddenly released to produce the sound. Similarly, the consonants [t, d, k, g] are produced by releasing pressure behind the tongue. Sounds like these are called plosives. Plosives are literally small explosions in the vocal tract, and therefore cannot be extended. They are very different, therefore, from the [f] and [v] sounds in five, which you can extend for as long as you have enough breath. For these sounds, the airstream passes through the articulators to produce audible friction, hence the name fricatives. As was the case for the plosives, the fricatives come in voiceless/voiced pairs: [f] and [v] are voiceless and voiced labio-dental fricatives respectively; the other English fricative pairs shown in the diagram above are  . Some consonants, known as affricates, combine a plosive and a fricative at the same place of articulation, as in the case of

. Some consonants, known as affricates, combine a plosive and a fricative at the same place of articulation, as in the case of  in English.

in English.

The plosive sounds we identified earlier involve a complete closure of the vocal tract: they are, in other words, kinds of stop consonants. But not all stops are plosives: another set of consonants involves complete closure but these consonants are nonetheless continuous sounds: these are the nasals [m, n,  ], which are produced by allowing air to pass through the nasal cavity.

], which are produced by allowing air to pass through the nasal cavity.

A final group of consonants, known as approximants, do not require closure of the vocal tract at all: the sounds are produced instead via the passage of air between articulators, which are close but not touching. Try producing the sound at the start of leap, and you’ll notice that the tip of the tongue touches the roof of the mouth around the alveolar ridge, but the passage of air which produces the sound actually passes along the sides of the tongue: for this reason this sound [l] is known as a lateral approximant. For most English speakers, the r sound in road is also an approximant, but this time the sides of the tongue are raised and the air passes through the gap between to produce a central approximant  .

.

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ينظم دورة عن آليات عمل الفهارس الفنية للموسوعات والكتب لملاكاته

|

|

|