Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 6-5-2022

Date: 23-2-2022

Date: 21-2-2022

|

Presuppositions and backgrounding

The everyday sense of presupposition encourages the view that presuppositions relate to something in the background. Indeed, this seems to be flagged by the etymological elements of the word: pre- meaning before, previous or earlier; and supposition meaning a hypothesis taken for granted. Lambrecht (1994: 52) emphasizes that presuppositions contain old information, while new information is what is asserted by the sentence. Stalnaker (e.g. [1974] 1991), as we saw, not only links presuppositions to background knowledge, but background common knowledge. However, while it is often the case that presuppositions background information in some way, and quite often that background information is common to participants, it is not the case that presuppositions are always restricted in this way. They can be used to foreground information, and new information at that. Although some earlier scholars (e.g. Karttunen 1973; Atlas 1975) recognized the possibility of, what one might call, unpresupposed presuppositions, it has been necessary for later scholars, notably Abbott (2000), to reinforce the message.

As Abbott elaborates, some presuppositional triggers seem geared towards presupposing new information, not old. It-clefts are a case in point. Let’s take our example in Table 3.1, It wasn’t me that drove fast, which presupposes that there is somebody who drove fast. Note that the presupposition appears last in the sentence, it has end-focus, and appears to be part of what is asserted – a feature which we said, is not characteristic of presuppositions. Then there are definite NPs. Readers may recollect that we showed how definite NPs, such as those in the Auden poem, were used to fill in a context; their referents were neither old information nor common information. We also demonstrated this in relation to stage directions in plays in the reflection box. A more specific case, as noted by Abbott (2000), concerns announcements involving presuppositions triggered by factive verbs such as regret, as in: British rail regrets that the ten o’clock train to Manchester has been cancelled (see also Lambrecht 1994: 61ff.). What is presupposed is the complement of the factive verb, yet it is clearly unlikely to be old information.

Generally, it is not difficult to find examples of factive verbs introducing new information, such as “I realized that he was the cause of the problem.” One may wonder whether all these are in fact just exceptional cases. But they are rather more frequent than one might think. Abbott (2000: 1428) reports that Fraurud (1990) found that about 60% of definite NPs in a corpus of Swedish introduced new referents, while only about a third were used anaphorically. She also reports that these findings were confirmed by Poesio and Vieira (1998) investigating English, and that more than half of the definite NPs in that study introducing new referents into the discourse also seemed to involve new information for the hearer. Similarly, Spenader (2002, reported in Andersson 2009: 735), encompassing a wider spectrum of presuppositions, found that 58% of presuppositions in conversation are used to introduce new information, and even to highlight it. The extent to which presuppositions do this, however, is context sensitive.

Let us glance at therapeutic discourse through the work of Andersson. Andersson (2009: 735) found that only 10.6% of presuppositions in therapeutic discourse introduce hearer-new information, but this is not surprising in this context, given that such discourse revolves around limited and familiar issues. Andersson (2009: 724) suggests that in therapeutic discourse presuppositions:

may serve (from both the patient’s and the therapist’s perspective) as technical tools whose objective is to maintain the overall continuity of the topic and enhance the discourse flow, but also as rhetorical devices used in order to influence the interlocutor, provide him/her with additional clues, enhance the claim, or, possibly, serve as avoidance or defense strategy.

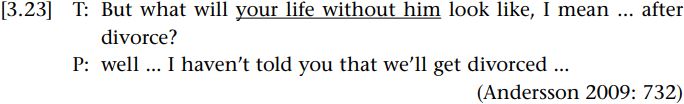

Consider this example (T is the therapist, P is first initial of the client’s name):

In Example [3.23], the definite NP your life without him (underlined above) in the therapist’s question presupposes that the patient has a life without his/her partner. This is reinforced by the temporal element after, presupposing that the divorce has happened. In response, P delivers a dispreferred second, challenging the presupposed information. Clearly, it is controversial. The therapist’s strategy here is to use presuppositions to force P to reflect on a particular aspect of a future world. The important general point here is that presuppositions allow the speaker to shape the context – the common ground – that is shared with their interlocutor. It is not simply a matter of presuppositions relying on a context already being shared.

Stalnaker (1991: 474) was aware of the issue: “[a] speaker may act as if certain propositions are part of the common background when he knows that they are not.” But Stalnaker downplays it, and his solution, namely that a speaker pretends that the hearer already knows the information, opens up all sorts of knotty problems. As noted by both Abbott (2000: 1425) and Atlas (2004: 45), Paul Grice (1981: 190) alludes to a solution:

It is quite natural to say to somebody, when we are discussing some concert, My aunt’s cousin went to that concert, when one knows perfectly well that the person one is talking to is very likely not even to know that one had an aunt, let alone know that one’s aunt had a cousin. So the supposition must be not that it is common knowledge but rather that it is noncontroversial, in the sense that it is something that you would expect the hearer to take from you (if he does not already know).

So, rather than whether it is old information or common information, or asserted or not, the issue is whether it is controversial information. Presuppositions could be said to be about noncontroversial information, “a speaker’s expectation that an addressee will charitably take the speaker’s word” about what is presupposed, rather than “expectations that they have in common the thought” of what is presupposed (Atlas 2004: 46–47). None of the above researchers do much to define the notion of (non)controversiality. It has the benefit of being wider than common ground. Information that is part of common ground is not likely to be controversial, but much general background information would be noncontroversial too. Perhaps one way of looking at this is to take noncontroversial information as expectable information, that is, it is consistent with your background knowledge (schemata) and inferences derived therefrom. Further, the above researchers do not suggest how this notion could be operationalized in naturally occurring interactions.

Nevertheless, we would argue that such a notion lends itself well to an interactional perspective. Here, presuppositions are pragmatic tactics with particular interactional and social functions. Our reflection box discussing the exploitation of presuppositions in discourses of power and persuasion is relevant here. In the courtroom discourse example given there, the defendant’s interactional response made it clear that she took the information presupposed in the question as highly controversial; she produced a dispreferred second-pair part following a question (i.e. it was not an answer). Importantly, note that in this case, but even more clearly in the case of the advertisements, the strategy on the part of the person producing the presupposition is to dupe the target into accepting the presupposition in some way without noticing – in other words, that they take it as noncontroversial, even though in other circumstances (e.g. after more careful thought) they might take it as highly controversial.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|