Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-11-16

Date: 2023-09-16

Date: 27-1-2022

|

We noted that the clause is an important unit of analysis because many head–modifier relations are found within the clause and because the criteria for constituent structure, such as transposition, apply best inside the clause. The sentence is not very useful in these respects; only a few dependency relations cross clause boundaries, and the constituent structure criteria do not really apply outside single clauses. Consider (2a–b).

Example (2a) contains a single main clause, which can stand on its own and constitute a sentence. Within that clause, there is a relatively dense network of dependencies. (Has) seen has the two NPs as complements – it requires both a noun phrase to its left and a noun phrase to its right. The form of HAVE must be has and not have, since there is agreement in number between the first noun phrase and the verb. If we replace Mr Elliott with a pronoun, the pronoun has to be him and not he. The Perfect, has seen, allows time adverbs such as just but excludes time adverbs such as in March or five years ago.

Example (2a) contains a single main clause, which can stand on its own and constitute a sentence. Within that clause, there is a relatively dense network of dependencies. (Has) seen has the two NPs as complements – it requires both a noun phrase to its left and a noun phrase to its right. The form of HAVE must be has and not have, since there is agreement in number between the first noun phrase and the verb. If we replace Mr Elliott with a pronoun, the pronoun has to be him and not he. The Perfect, has seen, allows time adverbs such as just but excludes time adverbs such as in March or five years ago.

Example (2b) contains the main clause Nurse Rooke has discovered where Anne Elliott stayed. The object of discovered is itself a clause, where Anne Elliott stayed. This complement clause is said to be embedded in the main clause and is controlled by discovered. Only some verbs allow a clause as opposed to an ordinary noun phrase, and DISCOVER is one of them. Of the verbs that allow complement clauses, only some allow WH complementisers such as where, and DISCOVER is one of them. Like DISCOVER, PLAN allows complement clauses (We planned that they would only stay for two nights – but alas …), but also infinitives, as in (2c); SUSPECT on the other hand excludes infinitives.

It is generally accepted that we can specify where words occur in phrases, and where phrases occur in clauses, but not where entire sentences occur in a text. This does not mean that the sentences in a text are devoid of links. Sentences in a paragraph can be linked by binders such as thus, in other words, for this reason, consequently, nevertheless, or by the ellipsis of certain portions of a sentence that depend on the preceding sentences in a discourse – I can help you tomorrow. Sheila can’t [help you tomorrow]; and by pronouns – Kerry and Louise have failed the maths exam. Margaret and Sheila are not pleased with them. The links between sentences in texts are different from the dependencies between the constituents in clauses, being less predictable and more flexible.

We can say something about where clauses occur in sentences. Relative clauses are embedded in noun phrases and immediately follow the head noun. (But not always, as in the well-used example I got a jug from India that was broken.) Verb complement clauses substitute for either noun phrase with a transitive verb. Anne in (3a) is replaced in (3b) by the complement clause That Captain Wentworth married Anne. The scene in (3c) is replaced in (3d) by the complement clause that he was still handsome. The complement clauses can be analyzed as occupying noun-phrase slots.

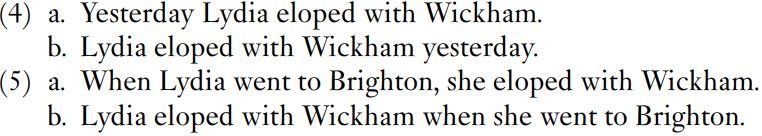

Time adverbs such as yesterday occur at the beginning of a clause or at the end of the verb phrase, as in (4), and adverbial clauses of time typically occur in the same positions, as in (5).

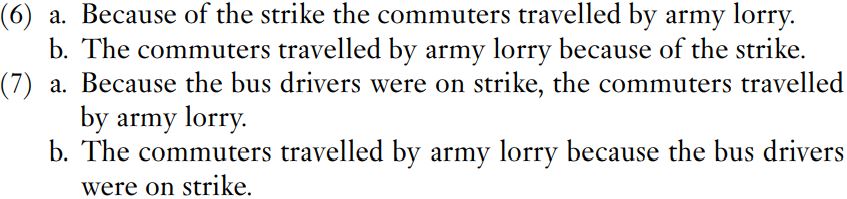

Adverbial clauses of reason behave in a similar fashion. Compare (6) with the phrase because of the strike and (7) with the clause because the bus drivers were on strike. Both can precede or follow the main clause, and both are optional (adjuncts).

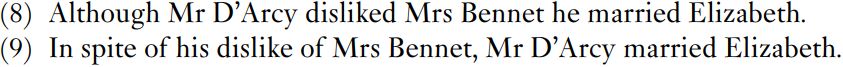

Clauses of concession and condition can also be seen as parallel to phrases (8), can be rephrased as (9).

Clauses of concession and condition can also be seen as parallel to phrases (8), can be rephrased as (9).

The phrase in spite of is not obviously a concession phrase, whereas yesterday and because of the strike are clearly time and reason phrases respectively. Example (9) nonetheless expresses a concession.

The phrase in spite of is not obviously a concession phrase, whereas yesterday and because of the strike are clearly time and reason phrases respectively. Example (9) nonetheless expresses a concession.

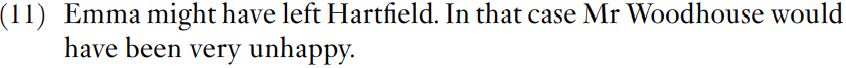

Another possible rephrasing is With Emma away from Hartfield, Mr Woodhouse will be very unhappy, but there is controversy, to be discussed later, as to whether sequences such as With Emma away from Hartfield should be analyzed as a phrase or as a kind of clause. In any case, the essential point is that most kinds of adverbial clause can be seen as substituting for adverbial phrases; we can state precisely where the phrases occur in a clause, and we can specify where the adverbial clauses occur, though rather less precisely.

Another possible rephrasing is With Emma away from Hartfield, Mr Woodhouse will be very unhappy, but there is controversy, to be discussed later, as to whether sequences such as With Emma away from Hartfield should be analyzed as a phrase or as a kind of clause. In any case, the essential point is that most kinds of adverbial clause can be seen as substituting for adverbial phrases; we can state precisely where the phrases occur in a clause, and we can specify where the adverbial clauses occur, though rather less precisely.

Let us review where the discussion has brought us. Traditional definitions of sentence talk of a grammatical unit built up from smaller units. The smaller units (phrases and clauses) are linked to each other by various head–modifier relations ; a given phrase or clause can only occur in certain slots inside sentences. Sentences themselves cannot be described as occurring in any particular slot in a piece of text. This definition implies that the sentence has a certain sort of unity, being grammatically complete, and has a degree of semantic independence which enables it to stand on its own independent of context. We have seen that the above definition applies better to main clauses. Sentences are better treated as units of discourse into which writers group clauses. Without going into detail, we should note that clauses are recognizable in all types of spoken and written language but that no reliable criteria exist for the recognition of sentences in spontaneous speech. Subordinate clauses are indeed grammatically complete in themselves and their patterns of occurrence can be specified, but they cannot stand on their own independent of context.

We have worked our way towards the following position. We can describe where words occur in phrases, where phrases occur in clauses and where clauses occur in sentences. We can describe how words combine to form phrases, phrases to form clauses, and clauses to form sentences. In contrast, we cannot describe where sentences occur, and describing how sentences combine to make up a discourse or text is very different from analyzing the structure of phrases and clauses. Finally, there are dense bundles of dependencies among the constituents of clauses; there is the occasional dependency relation across clause boundaries but none across sentence boundaries (in English). Links across sentence boundaries are better treated as binders tying small units together into a large piece of coherent text.

All the above are reasons for recognizing the clause as a unit between phrase and sentence.

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتبة أمّ البنين النسويّة تصدر العدد 212 من مجلّة رياض الزهراء (عليها السلام)

|

|

|