Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 20-1-2022

Date: 2023-07-27

Date: 2023-09-20

|

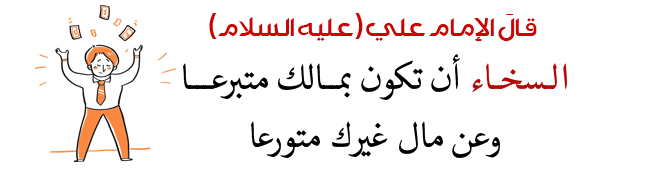

As we’ve seen above, some allomorphy is regular enough to be captured by phonological rules. But not all allomorphy is regular. Take, for example, past tenses of verbs in English. We have already looked at the regular past tense. Every native speaker or student of English knows that there are also quite a few verbs that don’t form the past tense by adding -ed. Consider table 9.1, which gives a selection of examples.

When we discussed the mental lexicon, we suggested that irregular past tense allomorphs are simply stored in the mental lexicon, and not derived by rules. So speakers of English have a lexical entry for the verb root sing, and along with it an associated entry for past tense sang. It is possible, though, that things are a bit more complicated. Think back to the experiment in section 6.3 where you asked a number of friends to make the past tense of the hypothetical verb gling. Probably a significant number of them offered either glang or glung. Since

this is not a real verb, clearly they didn’t have a past tense stored for it. Rather, they must have been making use of some sort of pattern to create these forms. In English there happen to be quite a few verbs whose present and past tenses show the same ɪ ~ æ alternation as sing or the ɪ ~ ʌ alternation of win. There appears to be an abstract pattern that speakers are tapping into here that relates a present tense with [ɪ] to a past tense with [æ] or [ʌ] if the verb ends in a nasal or a nasal plus some other consonant (for example, like swim, ring, sting, win, stink). Psycholinguists continue to work towards figuring out the exact nature of such patterns.

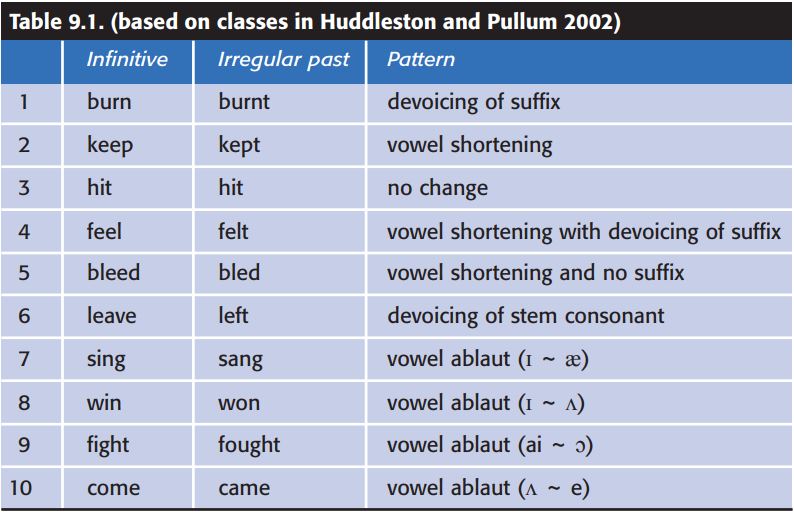

The example of unpredictable allomorphy we looked at above concerns English inflection. Let’s look at another example that has to do with derivation. Consider the forms in (10):

All of the verbs in the lefthand column have noun forms with the suffix -tion. But if you compare the transcriptions of the verbs and nouns carefully, you will see that both the verb bases and the derivational affix have various allomorphs. For example, the suffix seems to be -ʌn in (10a and c) but -eɪʃʌn in (10b). It looks like -uʃʌn in (10d), but -ɪʃʌn in (10f), and -ʃʌn in (10g). In (10a, c, and e) the [t] at the end of designate, prosecute, and expedite seem to have changed to [ʃ], the [v] at the end of resolve seems to have disappeared, and the [b] at the end of absorb has changed to [p]. And if you look carefully at many of these forms, the stress pattern on the derived noun is different from that of its verb base (the stressed syllable is shown in boldface). In other words, there is quite a complicated pattern of allomorphy associated with this suffix.

Is it predictable? Parts of it are. For example, if a verb ends in [v] and has a derived noun with the -tion suffix, it will always lose its [v] and the suffix will be pronounced -ution (think about the derived nouns for dissolve, absolve, revolve, etc.). Similarly, if a verb ends in [t] and takes the -ion suffix, the [t] will become [ʃ]. And if a verb ends in [z] or [d] and takes the -tion suffix, those consonants will become [ʒ]. Since the sounds [ʃ] and [ʒ] are palatal sounds, this process is called palatalization.

But the choice of allomorphs is not entirely predictable. For example, it’s not clear if we can predict when we will get -ation, say, as opposed to -ion on a particular verb base: we find -ation on the verbs unionize and refute, but not in circumcise and prosecute; those have the -ion allomorph. The derived noun form from combust is combustion, but that of infest is infestation. Why not combustation and infestion instead? The verb base propose yields proposition, but accuse yields accusation. Why not proposation, or accusition? To some extent the choice of allomorphs seems to be quite arbitrary.

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتبة أمّ البنين النسويّة تصدر العدد 212 من مجلّة رياض الزهراء (عليها السلام)

|

|

|