Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-11-01

Date: 2023-11-21

Date: 2023-08-15

|

By the mid-nineteenth century, members of the English Philological Society had come to feel that Johnson’s dictionary was inadequate. As we saw above, Johnson had missed many words, and even if he had not, over the course of a century many new words are added to a language and many old words come to be used in new ways. After much deliberation and a number of false starts, the Philological Society chose James Murray, a Scottish schoolmaster, to edit the New English Dictionary. Oxford University Press contracted to publish it, and by 1895 it had come to be known as the Oxford English Dictionary. Murray began work on the dictionary in 1879, hoping to finish it within ten years. But it would be almost fifty years before the first edition of the dictionary was finished, during which time three more editors were added, and Murray himself died.

The OED took so long to compile because the goals of its originators were so ambitious. Murray and his colleagues sought to create a dictionary that would not only give current meanings of words, but also trace those words back as far into the history of English as they could, taking note of all the spelling variants and meaning changes along the way. Following Johnson’s dictionary, all senses of words would be illustrated with quotations from literary works. Words that were already archaic or obsolete by the late nineteenth century would still be included, as long as they had not died out before 1250 CE. The dictionary was to be comprehensive in both breadth and depth, a task which turned out to be far more challenging than anyone in 1879 could have anticipated. The first edition of the OED ran to ten large volumes and contained almost a quarter of a million main entries. By the time the last volume was finished, the early volumes were already obsolete; one supplement was added in 1933, and a second one in 1972. A second edition of twenty volumes was issued in 1989, incorporating all of the supplements into the original volume. Today, work continues on the third edition, with segments issued on-line on a quarterly basis, as they are finished. Since the first edition, the OED has grown to include more than half a million entries; in its on-line form, size and space are no longer as much of a concern as they once were.

James Murray was well aware both of the weight his lexicographical decisions carried and of his potential fallibility in making those decisions – after all, most people do look to the dictionary to determine whether xyz really is a word. Perhaps Murray put it best when he noted in the Introduction to the first edition that:

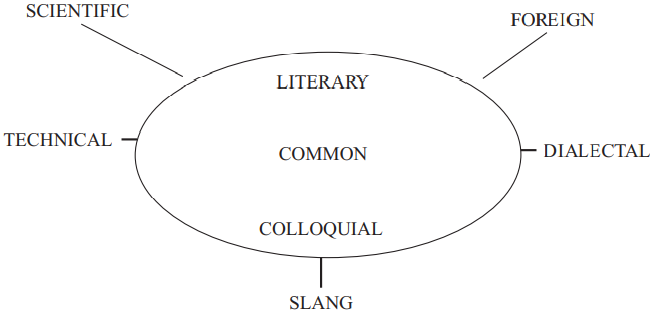

The Vocabulary of a widely-diffused and highly-cultivated living language is not a fixed quantity circumscribed by definite limits. That vast aggregate of words and phrases which constitutes the Vocabulary of English-speaking men presents, to the mind that endeavours to grasp it as a definite whole, the aspect of one of those nebulous masses familiar to the astronomer, in which a clear and unmistakable nucleus shades off on all sides, through zones of decreasing brightness to a dim marginal film that seems to end nowhere, but to lose itself imperceptibly in the surrounding darkness.

In other words, it’s impossible to pin down the vocabulary of English (and we might add, any other language).

reproduced from the Introduction to the first edition of the dictionary. His idea is that there is a core of words whose place in the dictionary nobody would dispute, encompassing what he called “common,” “literary,” and “colloquial” words. Common words are words that occur in all registers of English, like mother, dog, walk, apologetic, wiggle, if, and, to, in, that, and so on. Literary words are words that we might recognize when we read, but would not necessarily use in daily conversation, words, for example, like omnipotent, notwithstanding, heretical, avatar, and ambulatory. And also among the core words would be colloquial words, ones that we use frequently in spoken language, but far less frequently in written or formal language, for example, grubby, pooch, and mad (in the sense of ‘angry’). But there is no clear dividing line between these words and words which are perhaps too technical or scientifically specialized (circumfix, triptan), not quite assimilated enough into English (tchachka, sambal oelek), too bound to a specific dialect (frappé, black ice), or too informal, impermanent, or bound too narrowly to a particular time or a particular segment of society (groovy, homie). Deciding which of these uncommon words merit inclusion in the dictionary is a judgment call, often based more on practical considerations – the size of the dictionary, its intended audience – than on strict linguistic principles. All lexicographers face this conundrum, and each one makes a slightly different decision.

The OED is certainly the gold standard for English dictionaries today. Nevertheless, it has its own idiosyncrasies. For example, it contains a number of nonce words, words that are attested only once. Indeed there are quite a few nonce words that the OED includes, even though it is unable to define them. A search, using the key words “meaning obscure” and “of obscure meaning,” turns up 87 words so labeled, including smazky, squirgliting, val-dunk, vezon, uncape, and umbershoot. Each bears an entry illustrated with one quotation, which unfortunately does not illuminate the word’s meaning. Nevertheless, these and 81 others like them made it into the OED!

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتبة أمّ البنين النسويّة تصدر العدد 212 من مجلّة رياض الزهراء (عليها السلام)

|

|

|