النبات

النبات

الحيوان

الحيوان

الأحياء المجهرية

الأحياء المجهرية

علم الأمراض

علم الأمراض

التقانة الإحيائية

التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

علم الأجنة

علم الأجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

الأحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

الغدد

المضادات الحيوية

المضادات الحيوية| The Shape and Spatial Organization of a Bacterium Are Important During Chromosome Segregation and Cell Division |

|

|

|

Read More

Date: 10-4-2021

Date: 28-5-2021

Date: 28-4-2016

|

The Shape and Spatial Organization of a Bacterium Are Important During Chromosome Segregation and Cell Division

KEY CONCEPTS

-Bacterial chromosomes are specifically arranged and positioned inside cells.

-A rigid peptidoglycan cell wall surrounds the cell and gives it its shape.

-The rod shape of E. coli is dependent on MreB, PBP2, and RodA.

-Septum formation is initiated mid-cell, 50% of the distance from the septum to each end of the bacterium.

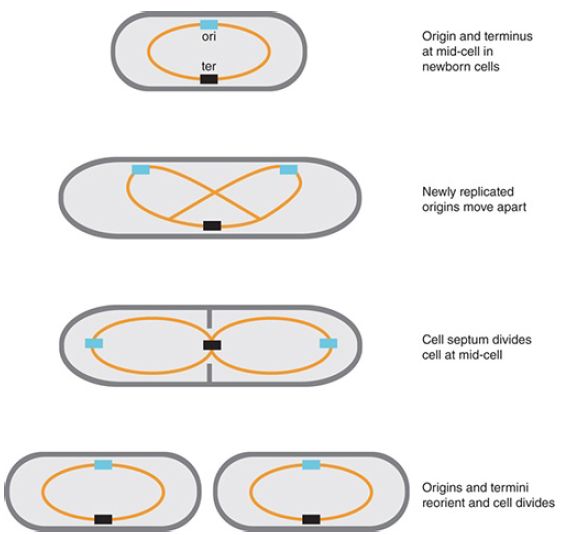

The shape of bacterial cells varies among different species, but many, including E. coli cells, are shaped like cylindrical rods that end in two curved poles. Bacterial cells have an internal cytoskeleton that is similar to what is found in eukaryotes. There are low homology homologs of actin, tubulin, and intermediate filaments. The bacterial chromosome is compacted into a dense protein–DNA structure called the nucleoid, which takes up most of the space inside the cell. It is not a disorganized mass of DNA; instead, specific DNA regions are localized to specific regions in the cell, and this positioning depends on the cell cycle and on the bacterial species. The movement apart of newly replicated bacterial chromosomes—that is, the segregation of the chromosomes—occurs concurrently with DNA replication. FIGURE 1.summarizes the arrangement in E. coli. In newborn cells, the origin and terminus regions of the chromosome are at mid-cell.

Following initiation, the new origins move toward the poles, or the one-quarter and three-quarters positions, and the terminus remains at mid-cell. Following cell division, the origins and termini reorient to mid-cell.

FIGURE 1. Attachment of bacterial DNA to the membrane could provide a mechanism for segregation.

The shape of a bacterial cell is established by a rigid layer of peptidoglycan in the cell wall, which surrounds the inner membrane.

The peptidoglycan is made by polymerization of tri- or pentapeptide-disaccharide units in a reaction involving connections between both types of subunit (transpeptidation and transglycosylation). Three proteins that are required to maintain the rodlike shape of bacteria are MreB, PBP2, and RodA. Mutations in any one of their genes and/or depletion of one of these proteins cause the bacterium to lose its extended shape and become round.

The structure of MreB protein resembles that of the eukaryotic protein actin, which polymerizes to form cytoskeletal filaments in eukaryotic cells. In bacteria, MreB polymerizes and appears to move dynamically around the circumference of the cell attached to the peptidoglycan synthesis machinery, including PBP2. These interactions are necessary for the lateral integrity of the cell walls, because the lack of MreB results in round, rather than rod-shaped, cells. RodA is a member of the SEDS (shape, elongation, division, and sporulation) family present in all bacteria that have a peptidoglycan cell wall. Each SEDS protein functions together with a specific transpeptidase, which catalyzes the formation of the crosslinks in the peptidoglycan. PBP2 (penicillin-binding protein 2) is the transpeptidase that interacts with RodA. This demonstrates the important principle that shape and rigidity can be determined by the simple extension of a polymeric structure.

The end of the cell cycle in a bacterium is defined by the division of a mother cell into two daughter cells. Bacteria divide in the center of the cell by the formation of a septum, a structure that forms in the center of the cell as an invagination from the surrounding envelope. The septum forms an impenetrable barrier between the two parts of the cell and provides the site at which the two daughter cells eventually separate entirely. The septum then becomes the new pole of each daughter cell. The septum consists of the same components as the cell envelope. The septum initially forms as a double layer of peptidoglycan, and the protein EnvA is required to split the covalent links between the layers so that the daughter cells can separate. Two related questions address the role of the septum in division: “What determines the location at which it forms?” and “What ensures that the daughter chromosomes lie on opposite sides of it?”

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتبة أمّ البنين النسويّة تصدر العدد 212 من مجلّة رياض الزهراء (عليها السلام)

|

|

|