The Sun as a timekeeper

المؤلف:

A. Roy, D. Clarke

المؤلف:

A. Roy, D. Clarke

المصدر:

Astronomy - Principles and Practice 4th ed

المصدر:

Astronomy - Principles and Practice 4th ed

الجزء والصفحة:

p 403

الجزء والصفحة:

p 403

4-9-2020

4-9-2020

1973

1973

The Sun as a timekeeper

By using suitable geometries, it is fairly easy to convert the changing directions of shadows of fixed objects to the apparent movement of the Sun across the sky and, hence, to the passage of time. Such a specially designed device is a sundial.

Sundials abound in a variety of forms. Two of the most common types are described here together with the ideas which are necessary to make and use them properly: these are the horizontal and the vertical types. In addition, the use of a simple noon-marker is described. Before doing this, it is important to have an appreciation of two terms which effect that position of the shadow and its relationship to time. These are longitude and the equation of time. (a) Effect of longitude. If two sundials are separated some miles apart in longitude, then the times at which the shadows fall on the noon-markers will be different: the further west the sundial, the later is the time for this event. Thus, if a time indicated by a sundial is to be converted to a civil time, allowance must be made for the sundial’s longitude in relation to the reference longitude used to define the local time zone. In Britain, particularly in the winter period, the situation is very simple. For sundials west of the Greenwich meridian, a certain period of time according to the value of longitude must be added to give the civil time and for sundials east of Greenwich, a time correction must be subtracted. In summer time, an additional hour must be added to all sundial times.

As an example, consider a sundial in Glasgow where the longitude is +4◦ 22' W, which is equivalent to 17 minutes 28 seconds of time. If t represents the time read from the sundial and T is the civil time, then T = t + 17min 28 s + 1 hr (if summer time is in operation). (b) The equation of time. The best system of timekeeping is one in which time flows at an even rate, i.e. each unit of time as it passes should equal any other previous unit time interval. If the time between successive transits of the sun across a north–south meridian is measured by an accurate clock, it is found that this interval is not constant through the year. In some seasons, it is speeding up and in others it is slowing down. The effect is due to the variation of the Earth’s speed as it revolves about the Sun in an elliptical orbit.

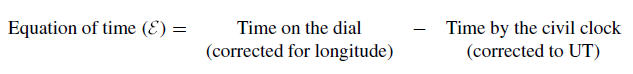

During those periods when the interval between successive transits is becoming shorter, it is obvious that the transits themselves must occur earlier each day and similarly when the transit interval is growing longer, the transits occur later each day. Relative to a noon defined by a regular clock, transits occur before that time in some seasons and after that time in others. The difference between the time indicated by the dial (corrected for longitude) and the civil time is known as the equation of time, i.e.

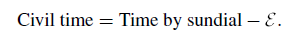

Thus,

Knowing the equation of time for the particular day allows a time given by a sundial to be converted to civil time.

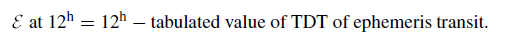

For some of the dials which may be found in your locality, the equation of time may also be tabulated on it. The equation of time is also tabulated in various books including, for example, Norton’s Star Atlas in which values are given rounded to the nearest minute. For more accurate values of the equation of time, daily values for any year may be determined from The Astronomical Almanac by noting the Terrestrial Dynamical Time (TDT) of the solar ephemeris transit and using the relation

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة