Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Commands (imperative sentences)

المؤلف:

PAUL R. KROEGER

المصدر:

Analyzing Grammar An Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

P199-C11

2026-01-19

18

Commands (imperative sentences)

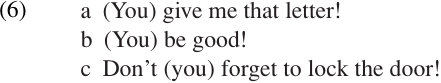

Now let us examine how commands are formed in various languages. The defining property of a command is that the hearer (or addressee) is being told to do something. This means that an imperative verb will always have a second person actor, which (in most languages) will be the subject. For this reason, any overt reference to the subject, whether as an NP or by verbal agreement, is likely to be redundant. Imperative verbs are frequently unmarked for person, even in languages which normally require the verb to agree with the person of the subject; and imperative clauses frequently lack a subject NP. Where there is an overt subject NP, it will always be a second person pronoun.

These features can be observed in the English examples in (6). With most English verbs the lack of agreement marking is not obvious, since the imperative form is the same as the second person present tense. But the lack of agreement morphology can be seen with the verb to be, as in (6b), since the normal second person form would be are.

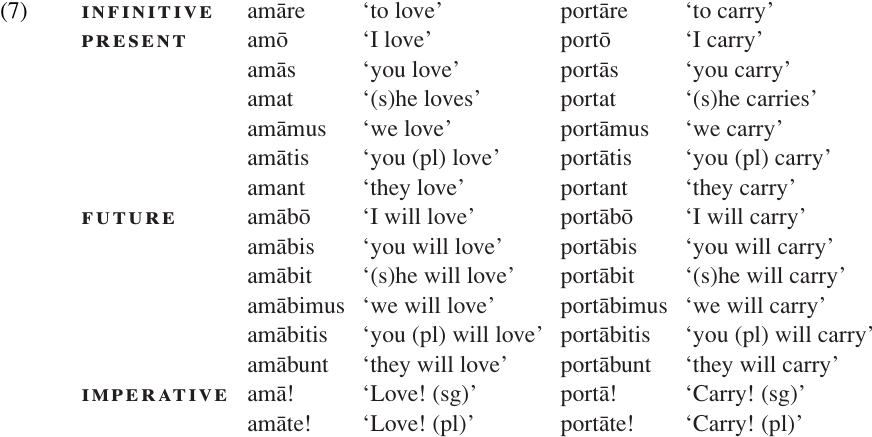

In languages that have morphological tense, imperative verbs are not normally inflected for tense. This seems natural, since an imperative always refers to a future event, and is most often intended to mean immediate future. In Latin, for example, the imperative is not inflected for tense, aspect, or person. It is thus distinct from the infinitive or any finite form of the verb, as shown in (7).3 However, imperative verbs are marked for number, and this is true in many other languages as well.

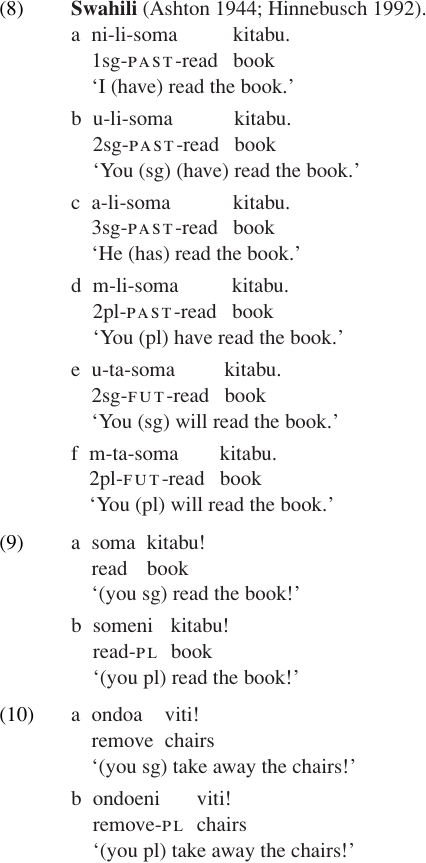

As these examples illustrate, imperative verbs are often morphologically simpler than a corresponding indicative form. In many languages, the imperative form is just a bare root. Even in languages which have a specific affix that marks imperative mood, imperative verbs often lack the normal markers for agreement and/or tense. Swahili provides another striking example. In most contexts, Swahili verbs bear obligatory prefixes which mark subject agreement and tense, as illustrated in (8).4 Imperative verbs, however, do not bear these suffixes. They are not marked for tense or person but only for number: -Ø for singular, -eni for plural. Some examples are given in (9–10).

In some languages, the “imperative” form of the verb is marked for person and can even take first- or third-person agreement markers. However, these uses of the imperative form are not really commands. The first person forms often have a hortative sense (e.g. Let’s eat!), while the third person forms often function as optatives (May he win the battle!).

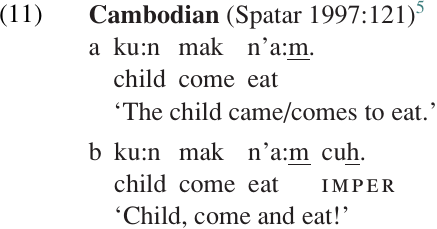

Aside from verbal morphology, another possible way of marking imperative sentences is by using a special particle. This is illustrated in (11) with examples from Cambodian (i.e. Khmer).

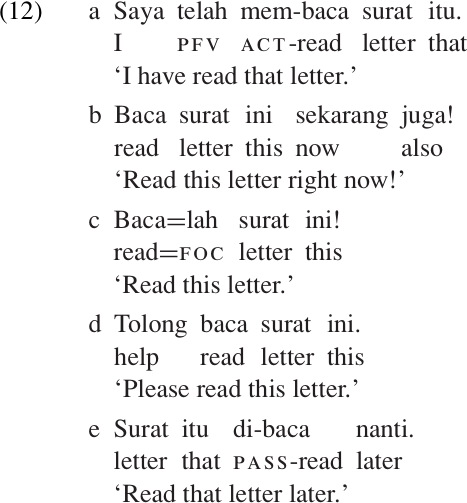

When we give a direct command to someone, we imply that we feel entitled to give such commands, whether this right is based on social status, official position, or personal familiarity. Status and familiarity are always sensitive issues, so most languages have a variety of methods for softening a command or making it sound more polite. In Malay, for example, a simple imperative is expressed using the bare verb stem. For transitive verbs like ‘read,’ this involves dropping the active voice prefix meN-; compare the verb in (12a) with the form used in (12b–e). One way of softening the command is by attaching the focus particle =lah to the imperative verb (12c).6 Other ways of forming a more polite command include inserting the verb tolong, literally ‘help,’ as in (12d); or using the passive form of the verb, as in (12e).

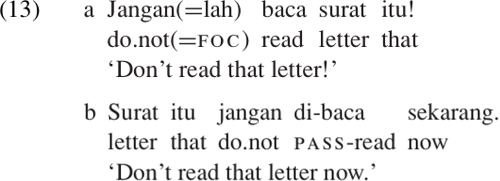

In Malay, as in many other languages, negative commands are formed using a special negative auxiliary verb jangan ‘do not!’ The same softening devices are available as with positive commands (13a, b).

3. Latin does, however, have a distinct “future imperative” form, used when there is an overt adverbial phrase designating a future time, or in “timeless” permanent instructions which are always in force (AllenandGreenough1931). Only the present and future tenses are shown in (7); see Analyzing word structure (24) for examples of past tense forms.

4. The precise function of the “indicative” suffix–a is a puzzle in many Bantu languages, and this suffix is not glossed in the following examples.

5. The orthography used in (11) is a transliteration of the Khmer script, rather than a representation of actual modern pronunciation. The symbol “m” represents the anusvara, or nikhahit, while symbol “h” represents the visarga.

6. This is true for Malaysian. However, Sneddon (1996:328) states that in modern spoken Indonesian=lah no longer has this function in imperatives for most speakers.

الاكثر قراءة في Sentences

الاكثر قراءة في Sentences

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)