Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Morphophonology

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P45-C2

2025-02-26

578

Morphophonology

Up to this point we have looked at allophonic variations (contextual variation of the sounds belonging to the same phoneme), which take place within a single morpheme. We should also point out that several of the processes that are shown to be crucial in accounting for the allophonic variations in languages can also be found active across morpheme boundaries. A brief discussion of these is useful, because they are frequent sources of confusion for students. When morphemes are combined to form bimorphemic (with two morphemes) or polymorphemic words, many of the assimilatory phenomena discussed can be present there too. Such things can also manifest themselves when two words are spoken consecutively. What we see in these instances, then, is the contextually determined alternations (different phonetic forms) of a morpheme.

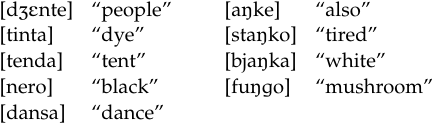

To illustrate what has been said thus far, let us look at the nasal assimilation rule in Italian we cited earlier (in Phonemic Analysis: A Mini-demo). For explicitness, we give the relevant details below.

As we see in the left column, [n] appears before [t, d, s, e] and, in the right column, [ŋ] appears before [k, g]. The sounds [n] and [ŋ] are in complementary distribution, since they share no phonetic environments. The velar allophone, [ŋ], appears only before velar stops, and the alveolar, [n], appears elsewhere. The phonetically motivated (nasal assimilating to the place of articulation of the following segment) contextual variation occurs within a morpheme, and thus qualifies for allophonic variation.

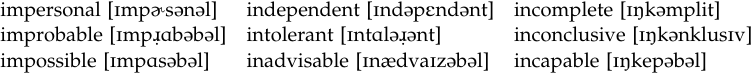

The same/similar phonetically motivated nasal assimilation is also found across morpheme boundaries in several other languages. Observe the following:

All the adjectives listed are preceded by the same negative prefix that manifests itself as either im or in orthographically. As for the phonetic manifestation, we have three forms: [ɪm] for the left column, [ɪn] for the middle column, and [ɪŋ] for the right column. That is, the pronunciation of the negative prefix is different only with respect to the nasal consonant, which is bilabial, [m], before adjectives that start with a bilabial sound (left column), and velar, [ŋ], before ones that start with a velar sound (right column). In other instances, the nasal is alveolar, [n], in the prefix (middle column). This predictable alternation of the nasal is the result of the place of articulation assimilation that is reminiscent of the Italian example discussed above. Although the phonetic motivation (place of articulation assimilation for articulatory ease) of this alternation is the same in these two situations, they are different structurally. While the Italian contextual variation was allophonic in nature (occurring within one morpheme), the case of the English negative prefixes does not deal with allophones of the same phoneme, but rather shows contextually predictable alternations among separate phonemes. That English [m], [n], and [ŋ] are not allophones of the same phoneme but belong to separate phonemes /m/, /n/, and /ŋ/ can clearly be shown by the following triplet: sum [sΛm], sun [sΛn], sung [sΛŋ]. Thus, what is revealed in the case of English negative prefixes is that there is an alternation of different phonemes for the same morpheme (indicators of the same meaning unit). Such cases are traditionally called morphophonemic alternations, and the different phonetic manifestations of the same morpheme (morpheme alternants) are called the allomorphs.

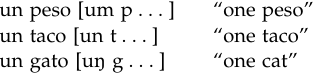

The previous case demonstrated allomorphic alternations across morpheme boundaries in the same word. These cases, however, are not restricted to morpheme boundary situations in one word but can occur across the boundaries of two separate words. For example, if we examine the phonetic manifestations of the morpheme meaning “one” in Spanish, we find the following.

While the morpheme meaning “one” in Spanish is consistently spelt as un, its pronunciation varies among [um], [un], and [uŋ]. Here, again, we have a familiar picture regarding the nasals assimilating to the place of articulation of the following obstruent. This time, however, the allomorphs (phonetically conditioned variants of the same morpheme) of the meaning unit “one” reveal the alternation across two words.

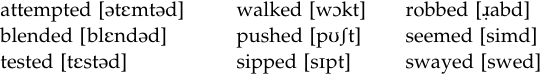

Another possibility is to find some feature-changing assimilatory processes that are restricted only across morpheme boundaries (i.e. acting only as morphophonemic processes), and with no parallels in allophonic processes of monomorphemic words. To illustrate this, examine the following past tense endings in English:

The above examples show that the regular past tense ending in English has three predictable phonetic manifestations. We have [-əd] if the last sound of the verb is an alveolar stop, /t, d/ (schwa insertion before another alveolar stop). If the verb-final sound is not an alveolar stop, however, then the shape of the past tense ending is an alveolar stop, [-t] or [-d], which is determined by the voicing of the verb-final sound. We have the voiceless [t] if the verb f inal sound is voiceless (middle column); however, the form is the voiced [d] if the verb-final sound is voiced (right column). This is a clear case of voicing assimilation. However, this does not mean that this sequencing restriction occurs throughout. While the past tense of the verb ban [bæn] is necessarily [bænd] and cannot be [bænt], this does not mean that we cannot have a final con sonant cluster with different voicing in its members ([-nt] sequence) in English.

Words such as bent, tent, etc. reveal that there is no such restriction within a single morpheme, and that the assimilatory situation is at work only across morpheme boundaries.

We should also mention that while morphophonemic alternations reveal several feature-changing assimilatory (phonetically motivated) processes, they are not limited to those only. Several other processes, such as epenthesis (insertion) and deletion of segments, as well as metathesis (transposition) of segments, can be cited among those.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)